John T. Scott (American, 1940–2007), Spirit Gates, 1994. Aluminum. Gift of Premier Bank, 94.263. © John T. Scott Artist Trust.

Facing the greenery of City Park, the majestic Spirit Gates at NOMA stand as a testament to centuries of artistic achievement by Black artists in New Orleans. While the gates poetically celebrate the city’s jazz traditions and ironwork craft, in this artwork John T. Scott also addressed a history of racial segregation in the City Park, and by extension, the New Orleans Museum of Art. Ayo Scott, the artist’s son, remembers his father speaking of the power in “replacing gates that once kept out people that looked like him, with gates that welcomed people that looked like him.”

The “Spirit Gates” at NOMA

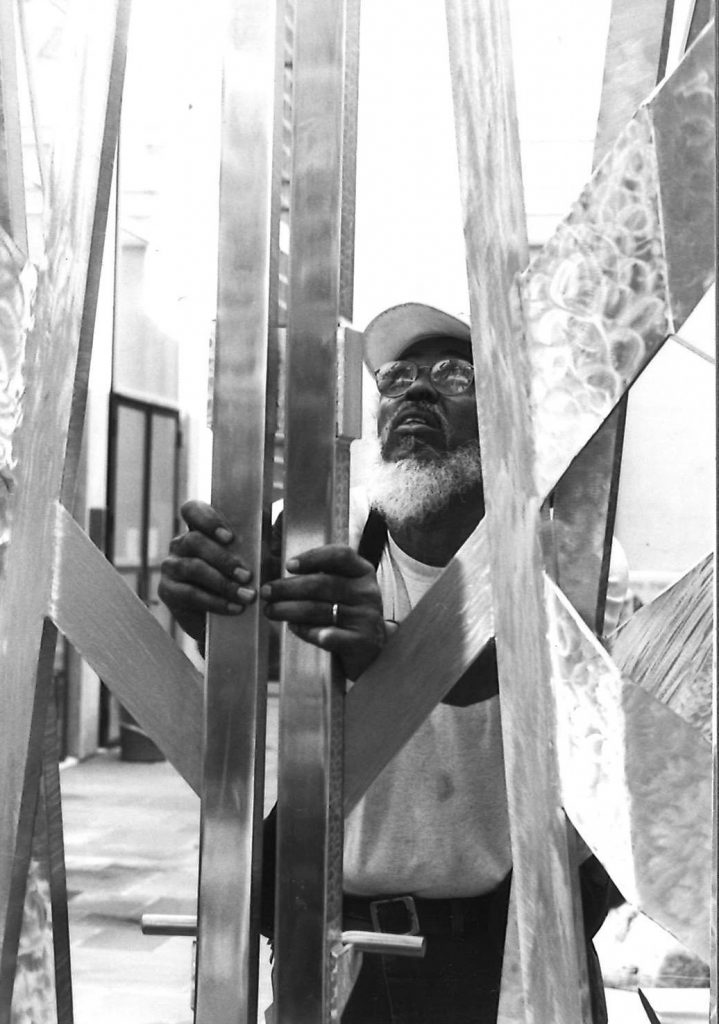

John T. Scott pictured with Spirit Gates, November 3, 1994. File photo from New Orleans Museum of Art archives.

The Spirit Gates were erected in 1994 at the completion of an architectural expansion to the museum. New Orleans artist John T. Scott was commissioned to create a gate that would secure a courtyard, but also open easily to allow entrance to visitors. The project needed to withstand rain, sun, and frequent touching. The defined architectural space set up physical constraints, including competing elements like the building’s classical relief, rooftop gargoyles, and walls of reflecting glass.

“My piece had to orchestrate what was there and stand on its own without setting up a dissonance,” noted Scott, likening the improvisational process of design to the art of jazz musicians. “I don’t imitate the music, but seek to capture its spirit. Jazz is a philosophy, not just a style of music.” And like jazz, Spirit Gates celebrates an individual artist’s voice, but was dependent on teamwork. The 13-foot-tall heavy aluminum structure took artisans more than 1,110 hours to create in Scott’s eastern New Orleans studio.

Scott’s Spirit Gates took form with an arrangement of triangles, cylinders, circles, and bars, all with varying brushed aluminum surfaces. Some shapes catch the sun like a mirror, others are dulled by the rhythmic pattern of the artist’s tool. The Modernist work is primarily abstract, but nonetheless calls to mind New Orleans’s famous wrought iron and lush tropical foliage.

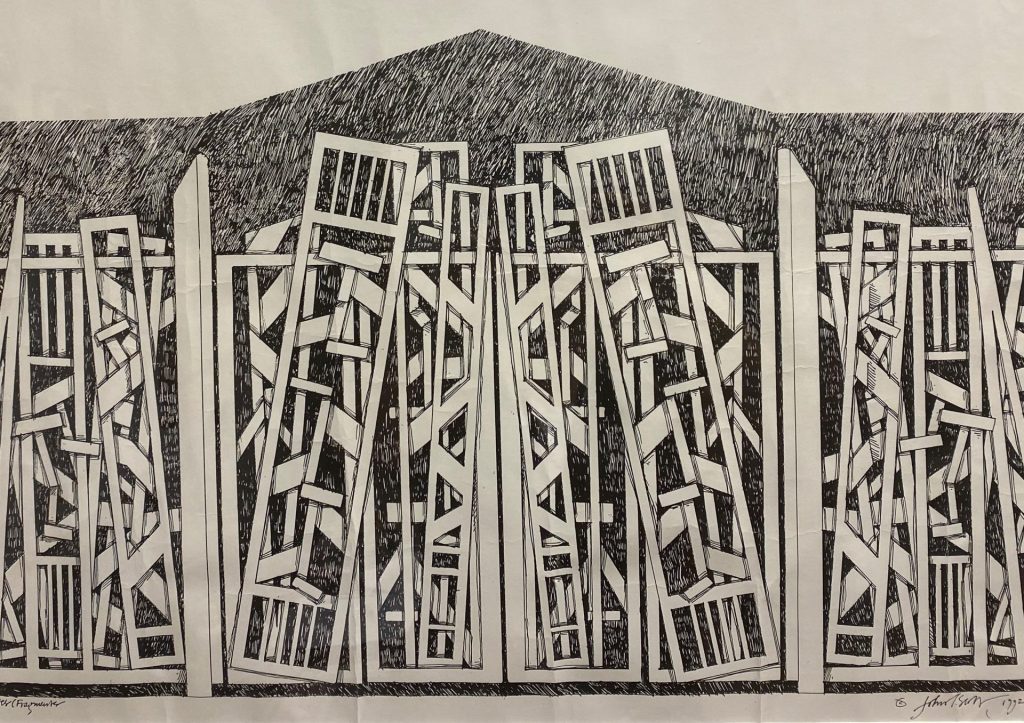

John T. Scott (American, 1940–2007), Study for Spirit Gates, 1992. Ink on mylar. Gift of John T. Scott, 94.276.

A Deeper Meaning

“Spirit Gates means a lot to me symbolically. To have an African-American create a piece of this size in City Park—a place that was long closed to Black people—is a way of acknowledging the heritage of my people in New Orleans.”

—John T. Scott, 1994

In a 1994 Times-Picayune article marking the unveiling of Spirit Gates, Scott noted that he carried mixed memories of the city’s largest art museum. Growing up in New Orleans, he recalled a grade school visit to the Delgado Museum (today’s NOMA) to see the work of Leonardo da Vinci. (In late 1952, the museum was host to an exhibition of models of Leonardo’s machines built by technicians of the IBM Corporation.) Scott noted that he had an uncomfortable sense of being an outsider in the institution. His feeling was a fact of law, given that until 1958 New Orleans City Park was racially segregated.

The 1994 interview continued with Scott saying he saw the museum as becoming more inclusive during his lifetime: “That’s important to me as an artist because I’m not just interested in my own culture, but all cultures. That’s not denying myself. It means recognizing myself as a part of something much larger.”

John T. Scott (American, 1940–2007), Spirit Gates, 1994. Aluminum. Gift of Premier Bank, 94.263. © John T. Scott Artist Trust.

The “Spirit Gates” Resonate Today

John T. Scott’s Spirit Gates serve to formally welcome all New Orleanians into the museum, physically and metaphorically. In speaking about his use of gates as framing devices across his artistic practice, John Scott notes they are part of an African heritage in which portals are metaphors for the experiences that mark the journey through life. In 1994 he said, “I recently lost my mother…. At the end of her life, the woman who taught me about life also taught me how to die. Passing through such gates enriches understanding. In that sense, the museum gates are a way of spiritually opening the museum to the wisdom of my ancestors.”

In an interview for this article, Ayo Scott, the artist’s son who is also an artist, recalled that the unveiling of Spirit Gates happened just after his grandmother’s passing. He remembers that evening the family saw a shooting star and had the “feeling she was there with us.”

Ayo Scott linked Spirit Gates to his father’s work at the 1984 World’s Fair in New Orleans. As art director for the large I’ve Known Rivers project that displayed an all-encompassing history of African-American culture, Scott and artist Martin Payton designed a simulation of the Middle Passage. Doors opened in front of and behind visitors to symbolize the forced transport of enslaved West Africans across the Atlantic. “The Spirit Gates do remind how far we have come. And, at the same time, thinking of George Floyd, how far we still have to go in achieving ‘justice for all.’”

John T. Scott pictured with Spirit Gates, November 3, 1994. File photo from New Orleans Museum of Art archives.

About John T. Scott

John T. Scott was born in New Orleans in 1940, and raised in the city’s Ninth Ward. After graduating from Xavier University, Scott earned a master’s degree at Michigan State University, where he studied with the painter Charles Pollock, Jackson Pollock’s brother. Returning to New Orleans, Scott taught at Xavier for more than 40 years, and chaired the art department from 1970 to 1984. His vivid, often kinetic, sculptures were featured in numerous public installations and exhibitions across the United States, including the 2005 survey at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Circle Dance: A John T. Scott Retrospective. At the height of his career, Scott was named a 1992 MacArthur Fellow. This highly prestigious honor, commonly nicknamed the “Genius Grant,” goes to extraordinary individuals for original work in art, science, literature, humanities, teaching, and entrepreneurship. Scott enjoyed a rich family life in New Orleans, raising five children with his wife Anna Rita Scott. The artist was displaced by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and passed away in 2007 in Houston, Texas.

To honor his lifetime of achievement, soon the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities will open the the Helis Foundation John Scott Center, an integrated arts space presenting the LEH’s collection of Scott’s artwork. Operating out of the historic Turners’ Hall in downtown New Orleans, The Center will also offer rich humanities educational opportunities on the environmental humanities, pandemics, poverty, and justice.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts & Design

Author’s Note

This article was written in coordination with the artist’s family, including Ayo Scott, and references John T. Scott quotes from Hilary Stunda’s “Playing It Straight, Upside Down and Backwards: A Conversation with John T. Scott,” in Sculpture magazine (October 2004) and Chris Waddington’s “John Scott’s Spirit Gates Unveiled Friday” in the Times-Picayune (November 3, 1994). It also includes information from the John T. Scott papers (1962–95) archived in the Amistad Research Center in partnership with Tulane University.

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.