In 1992, contemporary artist Fred Wilson set out to “mine” the collection of the Maryland Historical Society. The African American artist, then age 38, ventured into the storage areas of the Baltimore-based museum, established in 1844, and emerged with artifacts that had not been on display, or ones that were relegated to less conspicuous galleries. With an unorthodox curatorial vision intended to turn museology on its head, Wilson juxtaposed the traumatic with the traditional. Slave shackles were placed among nineteenth-century silver repoussé vessels. A whipping post was included within a display of handcrafted furniture. The white hood of a Klansman was draped in a baby carriage. Mining the Museum set records of visitation for the Maryland Historical Society and ignited a soul-searching discussion that continues today about the role of museums in presenting a more expansive—and often uncomfortable—interpretation of global history in art and artifacts.

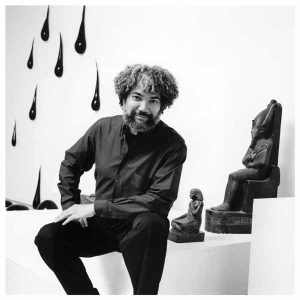

In the years that have followed, Wilson’s artistic practice continues to probe suppressed narratives and the representation of race in museums. In 1999, he was awarded a “Genius Grant” from the MacArthur Foundation. He will join New Orleans-based artist Ron Bechet in conversation on Thursday, October 24, at 6 pm in NOMA’s Auditorium for the 2019 Donna Perret Rosen Lecture. The event is free for members; nonmembers will be asked to pay standard museum admission. Seats may be reserved at this link.

In advance of his talk, Wilson spoke to NOMA Magazine about some of the themes that shape his artistic vision and his role as a cultural provocateur.

What was your first exposure to museums?

I grew up in museums. My mother was an artist, we lived in New York City, so she took me to lots of museums. Coming out of art school, I began working in museums, first as a security guard at my college museum, and then as in the 1970s as a freelance educator at both the Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan.

Working behind the scenes in a museum made me understand how different one’s perspective could be of museums from day-to-day as opposed to someone visiting every once in a while. You become more aware of the collection, where things are a little more unceremoniously kept, you sort of see that these objects have different lives. From my experience as an artist and also going through art school, I began to notice all the different ways that the museums discuss work, display work, and how, through displays, they are presenting their version or an image or through the labels of what you should be thinking about the particular object.

Cultural objects and historical objects have many stories to tell, and the institution chooses one story. I found it very frustrating even when I was young with what museums were leaving out. And so, as I approached the opportunity to create Mining the Museum, these are the thoughts that I was having: the great opportunity to actually go into a museum and work with their objects, to reveal other meanings behind the things that are displayed so that the public can be aware that they’re making a specific choice about what their collection is about.

Knowledge is power and the opportunity to understand that you could choose another storyline, or you could imagine another storyline, or just know that there are other things that could be told, I think that’s greatly important for institutions. Not that they need to change their stories all the time. It’s just that the public needs to know. It’s like if you read one newspaper all the time, don’t look at anything else, you might not be aware that there are other other ways to view a particular subject.

I also started making exhibitions of my peers’ work in different galleries, alternative galleries. By looking at the objects that I had available to me, I began to create the exhibitions that might have a different vantage point, different view. These installations, while not exactly museum quality, looked like museums with the lighting and the wall text and the wall color, and the display cases, but the messages were different than a traditional museum.

How did the Mining the Museum exhibition come about?

In 1992, the Contemporary Museum in Baltimore was a museum without walls, but they were inviting artists to do things in unusual spaces in that city, so they invited me to do a project at a museum in Baltimore based on these fake museums that I had been creating. They thought, Well, why not bring him to use a real museum? We went to all the museums in Baltimore, meeting with curators and directors. And I chose the Historical Society because I thought they hadn’t thought about museum display in a very long time. It was sort of frozen environment of a historical society, and everybody can imagine what that looks like.

To my surprise they said yes. I had this treasure trove of objects and images to work with from their entire history of collecting. There were certain things I didn’t even know existed. Like the whipping post, I had no idea that that actually existed. It came to the Historical Society in 1958 or ’59, right from the front of the city jail, where it’d been used in 1958, and then just sat in the basement because the museum was really an art and history museum. It really erred on the side of art and connoisseurship, not so much a deep dive into history.

Museum people are always really nice. I may be doing something that they’ve never done, that they wouldn’t do. But I’m a guest in their home, basically. I would look through the ledger books, and they were all very supportive of pulling up from the storage rooms whatever I wanted to use.

I worked on Mining the Museum over a year’s period. It’s very few projects that I’ve been able to have that much time with since then. It opened for the American Association of Museums conference. And I think that was the initial impetus to invite me to do that. As I like to say, had they not liked the exhibition, which was on the third floor, they would just closed up the third floor and said, Oh, we don’t have a third floor.

I’m interested in beauty because it draws you into looking, maybe not thinking but looking, at something. And what I try to do, through juxtaposition and other contexts, is to reveal something that is within the object, that has something to do with the object, that coaxes you beyond just the beauty and see some of the reasons for the object to be in the world, or how the world treats the object. And that’s by juxtaposing things or the magic of display. Not veering too far away from how the museum’s displays things but putting things in juxtaposition that reveal other aspects of history of the objects or the context that the object was originally in, even as beautiful as it might be. Beauty is a very seductive thing and I’d love the seduction of that.

I also think that beauty and the service of meaning is, even outside of the museum projects that I do, when I’m making objects such as chandeliers or mirrors or whatever. It’s a way to kind of connect with the viewer while giving them other ideas and other things to think about as they enjoy how it looks. There’s always a context. It’s my own, trying to make you aware of the context and how important that is to your understanding of the object. You can take that not only throughout the museum, but as you leave the museum.

It’s been more than 25 years since Mining the Museum. Based on your observations and the museums you’ve visited, do you think that they are doing a better job of presenting a broader scope of telling these stories?

I think to varying degrees, depending on the institution, I do. And people have also told me that they see situations or exhibitions or parts of exhibitions that were obviously influenced by my work. And I think that’s always great. I do think that curators are thinking about the objects in more complex ways and trying to create displays that, in their ways, make more complex the subjects of the objects. It’s to varying degrees how well or what they do. But I do see them grappling with it and trying to do it.

Obviously it’s been a long time, as you said, and museums are becoming more diverse in their collecting habits. In particular I’m thinking about contemporary art. You can see within, at least the labeled, their awareness of the complexity of some of their objects that if they’ve been there for several hundred years. And even some museums are really thinking about diversity on their staff as an important aspect of who they will employ into the future, if they haven’t already begun that process, as many museums have.

I feel there’s great promise. And here in New York, because I know it pretty well, the institutions are constantly retooling their exhibitions, constantly thinking about the diversity of their staff and the various perspectives of their staff, and developing their collections in ways that are truly representative of what’s going on out there. You live long enough, you have great hope about things and obviously young people. And the great thing about young people’s that they’re just coming into it as it is now and really want to push it even further, which is fantastic.

Read more about Fred Wilson’s installation at the 2017 Istanbul Biennial. Afro Kismet explored the history of Afro Turks through materials including glass chandeliers, monumental Iznik tile walls, cowrie shells, engravings, photographs, and Yoruba masks—all building upon research originally conducted for the 2003 Venice Biennial.