Leah Chase operated Dooky Chase, a Creole restaurant in New Orleans named after her husband, from 1946 until her death in 2019.

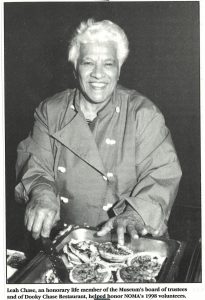

News of the passing of chef, restaurateur, and New Orleans goodwill ambassador Leah Chase on June 1, 2019, at age 96 has been met with an outpouring of tributes nationwide from celebrities, politicians, friends, family, and the thousands who enjoyed her cuisine and hospitality at Dooky Chase’s restaurant. The New Orleans Museum of Art shared a special bond with Mrs. Chase for more than four decades. In 1977 she joined the Board of Trustees, and she served as an Honorary Life Member in her later years until her death. Her dedication to NOMA was made evident in her many talents and deeds of which she gave freely, from cooking and serving meals to volunteers and serving as a mentor to interns, to chairing the museum’s volunteer committee and persuading others in the community for donations that allowed for purchase of works by artists of color.

Susan Taylor, NOMA’s Montine McDaniel Freeman Director, shares her thoughts on the role Mrs. Chase served in supporting and promoting the museum.

New Orleans has lost one of its most beloved personalities, Leah Chase, a woman whose passion for cooking and hospitality was matched only by her devotion to the arts. We at NOMA are deeply indebted to Leah for her decades of selfless service and her exemplary leadership. Lauded for her tireless work as both an award-winning restaurateur and unflinching civil rights activist, Leah’s legacy also includes philanthropy and volunteerism at NOMA which ultimately expanded the museum’s collection of works by African American artists and broadened our community outreach.

Leah believed strongly that both the body and the mind needed to be fed — and fed well. She viewed access to art as vital to nourishing the soul. New Orleanians and visitors who have had the privilege of eating there know that the walls at Dooky Chase’s restaurant are filled with works by African American artists, including Jacob Lawrence, John T. Scott, Elizabeth Catlett, and John T. Biggers. Although her collection was among one of the most celebrated personal collections of African-American art, Leah admitted that she was well into her fifties before she set foot in a museum, due in large part to a youth defined by Jim Crow restrictions. Recalling that deprivation, in 1995 she testified on Capitol Hill as an advocate for the National Endowment for the Arts. “Art softens people up and warms them up to deal with each other in humane ways,” she said, adding that “neighborhood kids, like me a long time ago, need to see something beautiful and breathtaking in order to aspire to higher things and to value living more.”

Indeed, Mrs. Chase always aspired to higher things and always encouraged others to stretch beyond perceived limitations. A highlight for NOMA’s summer intern program Creative Careers, designed to introduce high school interns to various types of museum careers, was a visit to Dooky Chase’s restaurant where these students were served not only traditional New Orleans fare, but also Leah’s pithy advice. And when she spoke, they listened. She encouraged students to pursue their dreams, and was particularly attentive to instilling confidence in young women. She encouraged other women as well, myself included. On my visits to Dooky Chase, Leah would regularly cheer me on, inspiring me with her kind words: “We need strong women in charge in New Orleans!” She was extraordinary in her support of our work with the community.

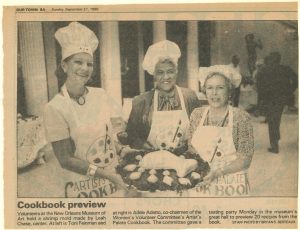

Leah also brought her cooking skills and irrepressible charm to NOMA where she robustly served as a member of the NOMA Volunteer Committee (NVC) for many years, well into her tenth decade. With the NVC, she acted as Activities Chair from 1981 to 1982, the Hospitality Committee Co-Chair for a remarkable 30 years, from 1983 to 2013, and as the Artist’s Palate Café Co-Chair from 1983 to 1989. Before we had Café NOMA, the NVC ran the Artist’s Palate Café to feed museum visitors. Leah was instrumental in this effort, and she later contributed to the Artist’s Palate Cookbook, published in 1986. Every year for decades, Leah donated food from Dooky Chase’s for the NVC Steering Committee and General Committee meetings. She found this work particularly fulfilling, as it merged her passions for feeding people, art, and service, and we loved seeing her warm smile at the museum for all of those years.

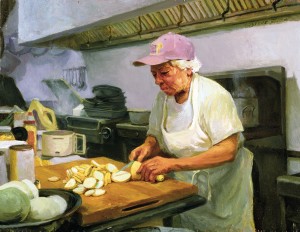

In 2012, NOMA exhibited a collection of 20 paintings by artist Gustave Blache III that captured Mrs. Chase at work in the her restaurant at every facet, from stirring the gumbo pot to greeting guests with her trademark open arms in the dining room. One of those works now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. NOMA’s exhibition of Blache’s works led to the creation of our Creative Corner in the first-floor elevator lobby. Set within the exhibition were table and chairs from Dooky Chase’s along with a guest book, asking visitors to record their favorite culinary memories. Despite the careful instruction, most of the entries were touching tributes to Leah Chase, messages of thanks, and memories made from dining Dooky Chase’s. We learned that visitors love to share their stories, and the experience was such a success that the Creative Corner is now a permanent component in our major exhibitions.

Leah’s commitment to opening all eyes to art was given a major boost in 2013—upon the occasion of her 90th birthday—when an acquisition fund was inaugurated in her name. Contributions large and small from more than 300 individual donors allowed NOMA to purchase works by emerging and underrepresented African American artists. Included were works by Mildred Thompson, Leonardo Drew, and McArthur Binion, which were featured in the 2017 exhibition New at NOMA: Recent Acquisitions in Modern and Contemporary Art. Thompson is an abstract painter and sculptor who, like Leah, fought against societal strictures for women and artists of color throughout her career. NOMA was the first major museum to present Thompson’s work, and she has since become internationally recognized as one of the most vital artistic voices of her time. After the exhibition, our Binion painting was loaned to the prestigious Venice Biennale. Leonardo Drew’s large wall relief was specifically commissioned for NOMA.

By example, Mrs. Chase worked tirelessly to ensure that the doors of cultural institutions were open to all. She once said of NOMA, “I used to think museums were just for the elite, and all you had were Old Masters works. I like those, but it’s important to have art that everybody can relate to. I want more people in the museum.”

At NOMA, we hold our many and varied memories of Leah close to our hearts, and every day we strive fulfill her wishes of representation and inclusivity. Rest in peace, Mrs. Chase, you will always be remembered.