Visitors enter Keith Sonnier: Until Today beneath an assemblage of bent neon tubes titled Passage Azur (2015/2019).

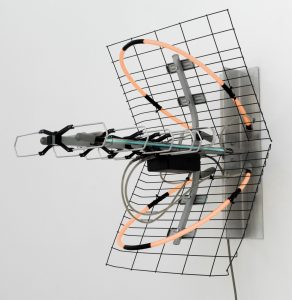

NOMA is aglow with neon through Sunday, June 2, in the exhibition galleries for Keith Sonnier: Until Today. Sonnier, born in 1941, was part of a group of artists who challenged preconceived notions of sculpture beginning in the late 1960s by experimenting with industrial and ephemeral materials. Frustrated by the standardized forms of incandescent light, he started experimenting with neon. Using copper tubing as a template, Sonnier began sketching lines, arches, and curves ultimately realized in glass tubing that encloses the electrified glow of neon. The linear quality of neon allowed Sonnier to draw in space.

Born and raised in the Acadiana region of southwest Louisiana, Sonnier cites the glow of neon in the hazy, humid nighttime air as an early influence. He described this early fascination in an interview from 1977: “These fluorescent light and glass pieces remind me a lot of driving in Louisiana . . . About the most religious experience I’ve ever had in Louisiana: coming back from a dance late at night and driving over this flat land and, all of a sudden, seeing these waves of light going up and down in this thick fog. Just incredible!”

What exactly is neon, and how did it come to light up the modern world? Presented here are five facts about the mysterious element that has long lit the imagination.

Neon is a colorless, odorless mostly inert gaseous element that is found in minute amounts in air. The name was given to the gas by its discoverers, the British chemists William Ramsay (1852–1916) and Morris William Travers (1872–1961) who were experimenting with liquified air. The word first appeared in their findings, “On the Companion of Argon,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London (Volume 63), published in 1898. According to a later account by Travers, the Latin name for the gas, novum, translated as “new,” was suggested by William Ramsay’s 13-year old son, and rendered in Greek by Ramsay to match the names of other recently discovered gases.

Travers wrote of the discovery, ‘The blaze of crimson light from the tube told its own story, and it was a sight to dwell upon and never to forget. It was worth the struggle of the previous two years; and all the difficulties yet to be overcome before the research was finished . . . for nothing in the world gave a glow such as we had seen.”

Neon became commercialized through the work of Georges Claude (1870–1960), a French engineer and inventor. He developed techniques for purifying the inert gases within a completely sealed glass tube and adding the electric spark to illuminate the element. Claude’s first public demonstration of a large neon light was at the Paris Motor Show in December 1910. In 1923, Claude and his French company Claude Neon introduced neon gas signs to the US by selling two to Earle C. Anthony, the owner of a Packard car dealership in Los Angeles, for $24,000. Angelenos were so captivated by the glowing tubes, traffic jams crowded the auto sales lot.

Neon quickly mesmerized Americans. Visible even in daylight, gawkers would stare for hours at what became known as “liquid fire.” Red is the color electrified neon produces. More than 150 colors can be created by using various combinations of argon, mercury, and phosphor. Elaborate neon signs soon took over urban commercial hubs, including New York’s Times Square, Fremont Street in Las Vegas, and Bourbon and Canal streets in New Orleans. Known as “spectaculars,” these mammoth neon signs with synchronized off-on capabilities can require miles of tubing.

The heyday of neon was the 1930s. Many signs were unplugged during the blackouts of World War II and never relit. Cross-country road travel in the 1950s popularized neon again, but by the 1960s beautification ordinances began to prohibit what was considered garish lighting for disreputable businesses. Preservationists have saved numerous signs across the country, most notably at the Neon Museum and “boneyard” in Las Vegas; the Museum of Neon Art in Glendale, California; the American Sign Museum in Cincinnati; and the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

In 2013 the Arts Council of New Orleans launched the Iconic Signage Project to illuminate businesses along Broad Street with retro neon signage, including the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club, the Godbarber Barber Shop, F&F Botanica Spiritual Supply, and the Crescent School of Gaming and Bartending.

Gallery of a select neon works by Keith Sonnier on view at NOMA:

Editorial intern Emma Coffman contributed to this feature.