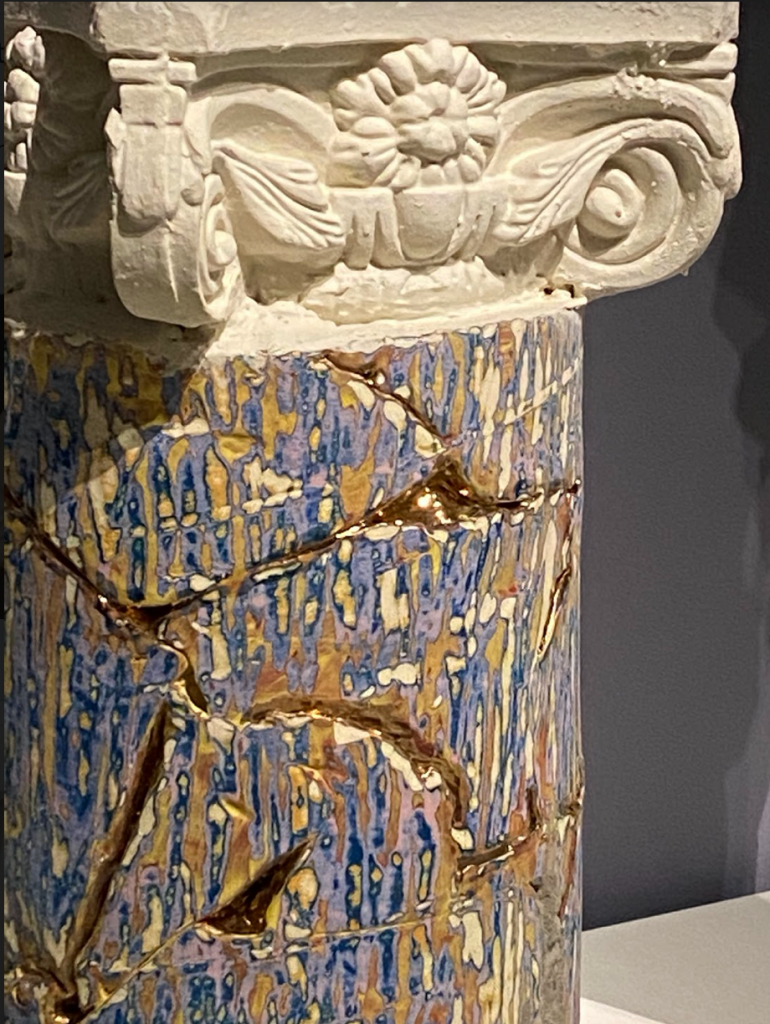

Robert W. Archambeau (Canadian, b. 1933), 9-11 Vase (detail), 2001. Stoneware, Kintsugi gold leaf repair; 15 x 15 x 15 in., Gift of Daniel Anderson and Caroline Anderson, 2019.78

Through a tumultuous 2020 it feels as if our lives are about to crack under the pressures of global pandemic, financial hardships, racial injustices, and a frustrating democratic process. For optimists, a soothing thought through increasingly difficult weeks has been the idea that we will, we must, emerge stronger as we mend our breaks.

More than 500 years ago, Japanese artists developed a technique that celebrates breakage as a part of life’s journey. This ceramic-repair methodology highlights cracks as part of the beauty and the history of an object, rather than something to disguise. Kintsugi, which translates to “golden joinery,” applies precious materials, like gold, silver, or platinum, as a mending filler for broken pottery. More than merely a craft technique, Kintsugi is a tangible display of the Japanese aesthetic philosophy of Wabi-sabi, the appreciation of imperfection, admiration for simplicity, and acceptance of transience.

The origin story of the Kintsugi repair craft is said to begin with the 15th-century Japanese shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (Kyoto, Japan, 1436–1490). After the ruler’s favorite Chinese porcelain tea bowl was broken, it was put back together in the traditional way with metal staples. Yoshimasa’s displeasure with the unsightly repair motivated craftsmen to find an alternative, more aesthetically pleasing way to repair broken pottery. The bowl’s cracks were filled and patched with layers of lacquer derived naturally from tree sap, with the last layer including a fine dust of powdered gold. This gilt repair celebrated the mending of the precious object, and the new art of Kintsugi was born when the tea bowl was restored as the shogun’s favorite.

In a beautiful 2015 video produced by Oxford University’s Pitt Rivers Museum, Muneaki Shimode and Takahiko Sato, lacquerware artists from Kyoto, demonstrating the Kintsugi technique of repairing ceramics. Their demonstration shows the time-consuming and delicate process with lacquer and powdered gold, and the artists explaining the spiritual value of the enduring Japanese craft.

In historic ceramic collections, the presence of intricate Kintsugi repair elevates the value–both monetary and philosophical–of ceramic objects. Some repaired ceramics would have been considered fine treasures before their break, but we often find that utilitarian clay wares are treated with the precious gold repair technique, establishing a modest stoneware bottle or simple tea bowl as a cherished object. This article includes beautiful examples of Kintsugi from the collections at the Victoria & Albert Museum (London), the Smithsonian’s Freer/Sackler National Museum of Asian Art, and The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. In historic examples of the Kintsugi, NOMA’s collection has a modest, but almost humorous example. This thirteenth-century celadon-glazed funerary jar from the kilns in Longquan, China has an obvious repair to its finial, giving the bird a bright gold head.

Contemporary clay artists turn to Kintsugi as a purposeful part of their work. NOMA’s collection includes the 2001 9-11 Vase by Canadian potter Robert Archambeau. The work cracked while being fired in a wood kiln. Instead of being discarded, the vase’s breaks are highlighted with gold in the traditional Japanese manner.

In a work currently on view at NOMA, the potter and poet Roberto Lugo makes use of Kintsugi in the pedestal base of his 2019 “Stunting” Garniture Set, a commissioned work for the museum that blends contemporary social issues with traditional porcelain pottery. The work’s base is three Neoclassical columns shown to be crumbling and graffiti covered, succumbing to the metaphorical weight of historical pressures. In this work, Lugo explores the idea that we find healing and beauty in mending those breaks, and that has the value of gold.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design

Virtual programs at NOMA are made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.