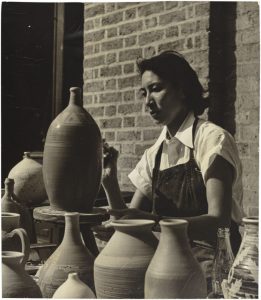

Jack Robinson, photographer (America, 1928-1997), Katherine Choy at a Kiln in New Orleans, early 1950s, Photo courtesy www.robinsonarchive.com

Some artists leave a lifetime of artwork to consider, even keeping records of their intention and their processes. Scholars write volumes detailing some artist’s earliest scribbles, education, patronage, family and loves. But some artists, like the brilliant Katherine Po-Yu Choy, leave the world too soon for all our questions to ever be answered.

In the early 1950s in New Orleans, Katherine Choy was one of the very first American ceramicists to bridge Asian clay traditions into emergent abstract Modern art. During her fervent short career, Choy quietly subverted ceramic traditions, drew wide acclaim through national art exhibitions, and then died too young at age 30.

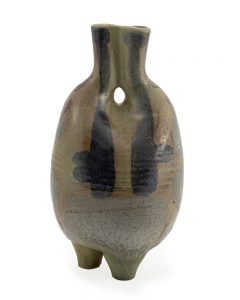

Katherine Choy (American, born China, 1927–1958), Double Spout Vase, 1952–1957. New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Evelyn Witherspoon, 87.153

Born into a wealthy merchant family in Shanghai, China, Katherine Choy immigrated to the United States from Hong Kong in 1946. She was just out of high school, and, as a 1953 New Orleans Item article notes, “since her childhood she remembered nothing but continuous war.” She attended Wesleyan College in Georgia, but graduated from Mills College in California in 1950. A 1952 Wesleyan alumni newsletter notes she transferred to California so “it would be possible for her to be with a member of her family.” Artistically, the move west allowed Choy to be educated among forward-looking American academics and artists in the Bay Area, especially in her chosen field of ceramics.

At Oakland’s Mills College, Katherine Choy studied under nationally-celebrated ceramics educator F. Carlton Ball. Ball was formative in establishing ceramics as an academic study, including devising potter’s wheels and clay mixtures that were affordable. Ball educated students on both new scientific techniques and the long history of the ceramic craft. Nurturing a community around ceramics, Ball invited Bernard Leach to give a two week workshop during Choy’s time as a Mills student. Leach and traditional Japanese potter Shoji Hamada had founded St. Ives Pottery (England) in the 1920s, famously presenting ancient ceramic traditions to 20th-century potters and espousing ceramics as a holistic way of life. Their workshops and 1940 treatise “A Potter’s Book” were enormously influential to young American potters, including Katherine Choy.

Academic communities hosting workshops for visiting potters was a critical avenue for the advancement of ideas around ceramic expression in the mid-twentieth century. Later in New Orleans, Choy would continue the tradition by inviting Carlton Ball to Tulane University for his own residency in 1954. The NOMA collection includes one stoneware bottle made by Choy and Ball working collaboratively during that time together in Louisiana.

F. Carlton Ball (American, 1911-1992) and Katherine Choy (American, born China, 1927–1958), Bottle, 1954. Stoneware. New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Barry Trinchard, 91.183.

After earning her MFA at Mills in 1950, Choy was awarded a scholarship for one year of advanced study at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. From 1951 to 1952, she studied with another important figure in mid-century American ceramics, Maija Grotell. Grotell was an influential Finnish-American artist often described as the “mother of American Studio Ceramics” in encouraging her students to find their own individual artistic voice.

In 1952, Katherine Choy was hired to head the ceramics department at Newcomb College at Tulane University. Soon after her arrival, the promising young artist was the subject of Ceramics by Katherine Choy at the Delgado Museum of Art (today’s NOMA) in May 1953. The exhibition checklist included 70 glazed vessels made in 1951, 1952 and 1953. The newspaper New Orleans Item profiled Choy on the occasion. Even the article title “Choy Po-Yu Ignores Tradition” connects Choy to Asian ceramic customs, but also highlights her moving beyond confines. “I don’t put fiery dragons on my ceramics just because Chinese tradition would dictate that sort of decoration,” Choy noted in the April 19, 1953 article. Instead, in this period Choy’s work shows a graceful restraint that subtly honors the Asian ceramic traditions as she begins to explore her own artistic vocabulary.

Victor Olivier, Jr.’s photograph of the artist demonstrating her process in the French Quarter (alongside the St. Louis cathedral in Pere Antoine Alley) shows the timeless shapes of her vessels in the early 1950s. Katherine Choy paired these classic vase shapes with increasingly painterly ornamentation and advanced glaze recipes she honed in the kilns at Newcomb College.

Victor Olivier, Jr., Katherine Choy at a Festival, Pere Antoine Alley, New Orleans, early 1950s. New Orleans Museum of Art, Archives.

As an arts educator and practicing ceramicist at Newcomb, Katherine Choy was engaged with the emerging 20th century field of critical color theory. She investigated color properties through chemicals in glazes for her pottery, but as a multidisciplinary instructor, also through color’s psychological effect in the final work of art. In 1957, Katherine and the art faculty at Tulane University invited artist Mark Rothko for a two month residency. Instead of formally teaching a class, Rothko, a preeminent artist of his generation, gave lectures and critiques with the Tulane community about the emotion, spirit, and expressive potential of color. Many New Orleans artists, including Ida Kohlmeyer, have spoken of the impact of Rothko’s color field theories and his New Orleans residency on their work.

Around the same time as Rothko’s residency in New Orleans, Katherine Choy was engaged in establishing the next chapter of her career. The dates around her departure from New Orleans are a little unclear. It is often noted that she was on the faculty of Tulane until 1957, but for at least a short time in 1956, Katherine Choy was employed as a textile designer in New York City. In a September 22, 1956 New York Times article about the Isabel Scott Fabrics fall collection, Katherine Choy was noted as a new designer that traces “her subtle sense of color…. to the influence of ancient Chinese porcelains.” Whenever she left specifically, ceramic sculptor and at-the-time Tulane MFA student Viola Frey came along for the ride. Frey recalls in her oral history for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art that “muggy hot weather from New Orleans was really oppressive, and so [Katherine] and I we drove from New Orleans to New York.”

Katherine Choy left Louisiana to advance her vision for cooperative community around expression in ceramic arts. With financial support from her family and unnamed patrons in New Orleans, in 1957 Choy founded the Clay Art Center in Port Chester, New York. Thirty minutes outside New York City by train, this new ceramic residency program occupied facilities previously owned by Good Earth Pottery. A friend from Mills College, Henry Okamoto, joined as a partner in running the Center, and soon they were hosting artists like Frey to explore the then-radical idea that clay could serve as an artistic medium beyond the boundaries of functional objects.

Katherine Choy’s community legacy continues today through the mission of the Clay Art Center, which is still thriving. But the artist herself left life too soon, passing away at age 30 in February 1958. Her New York Times obituary notes that Choy was survived by her husband Wen-chung Chou, a composer she had married in late 1957, and her parents Mr. and Mrs. Wai-man Choy.

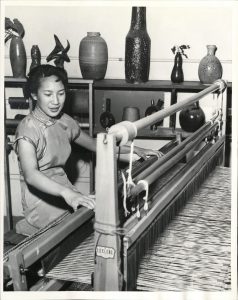

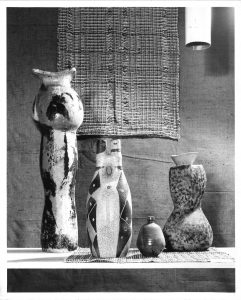

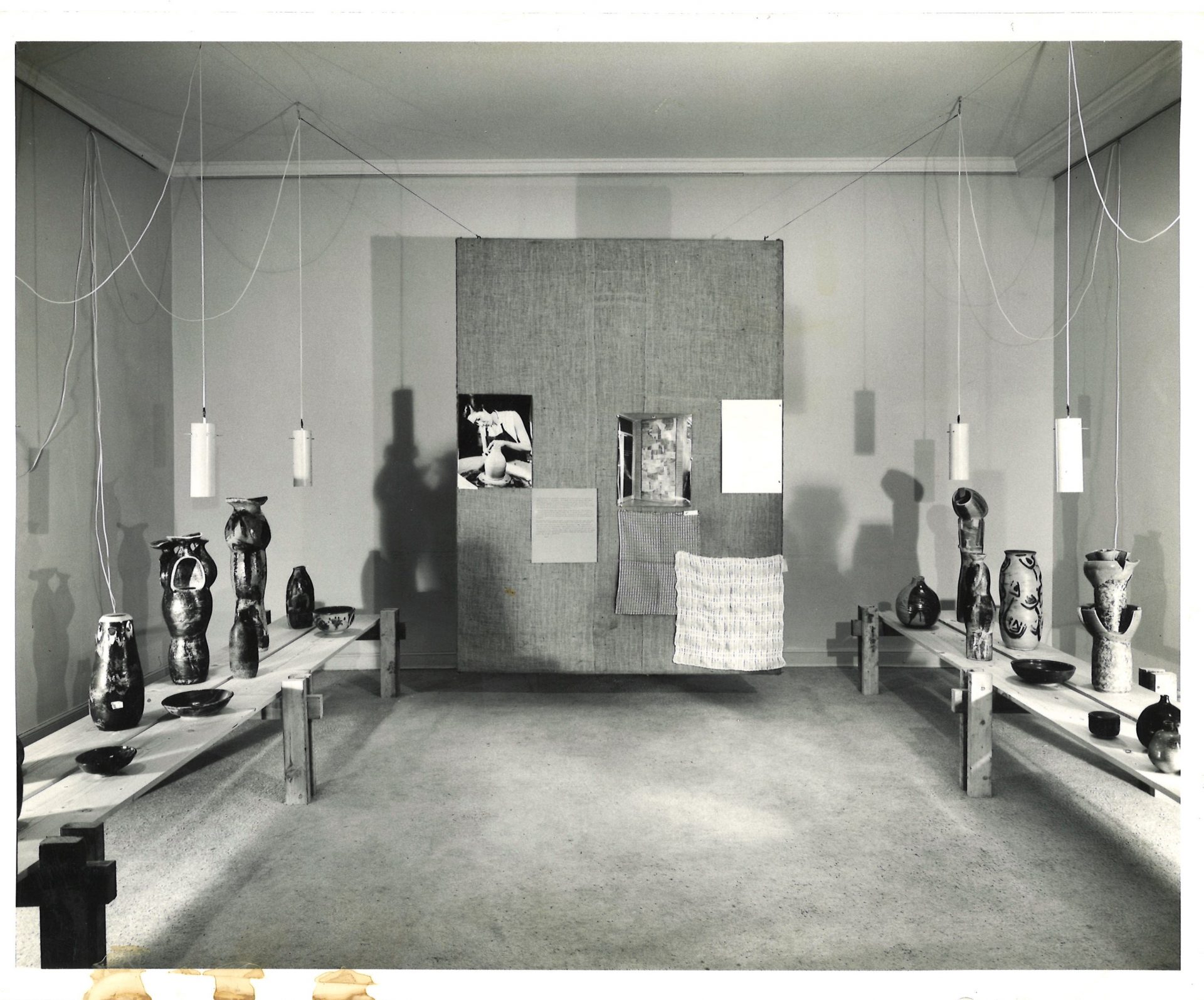

Ceramics and weaving in Katherine Choy Memorial Show, Orleans Gallery, New Orleans, Sept 13 – Oct 3, 1959. Photography by Stuart Lynn

A series of exhibitions memorialized Katherine Choy in the late 1950s and 1960s. New York’s Museum of Contemporary Craft (today’s Museum of Art & Design) held an exhibit in June 1961 pairing Choy’s pottery with wall hangings by Mariska Karasz, a Hungarian textile artist that had passed away in 1960. In Louisiana, the Orleans Gallery–the artist-led 1956 to 1972 gallery that promoted contemporary art from New Orleans–mounted the Katherine Choy Memorial Show in fall 1959. Clear from installation views of this exhibition is how much Katherine Choy’s work evolved in the mid-1950s. The ceramics explored in her final year at the Clay Art Center show a powerful originality.

Choy’s clay vessels on view at the Orleans Gallery show painterly abstraction in glazes, bold asymmetry in forms, and experimentation with jagged and broken shapes. Katherine Choy was working in an expressive way and at a large scale that nearly no American ceramicist was attempting in that decade. In this quietly celebrated artist, there is a too-often-unsung critical development in clay, running in parallel to (or perhaps before) one of clay’s most innovative voices, Peter Voulkos. Voulkos is rightly heralded for destroying conventions to elevate the expressive and active possibilities of clay in the late 1950s, but with thoughtful consideration, we should be adding Katherine Choy to the credits for radicalizing 20th-century ceramics.

Katherine Choy Memorial Show, Orleans Gallery, New Orleans, Sept 13 – Oct 3, 1959. Photography by Stuart Lynn.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts & Design

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.