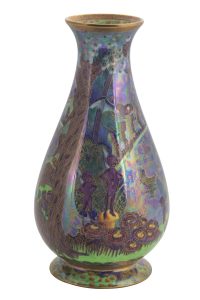

Wedgwood, manufacturer, and Daisy Makeig-Jones, designer, Fairyland Lustre “Imps on a Bridge and Tree House” Vase, 1916–1931. Porcelain (Bone china) with underglaze and luster and gilt; 12 in x 6 1/2 in diameter, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Sydney Besthoff III, 2007.70.

Radiantly glazed and richly imaginative, Fairyland Luster pottery represent one of the most extraordinary technical achievements in the modern ceramic industry. Wedgwood designer Daisy Makeig-Jones (British, 1881–1945) combined whimsical children’s illustrations with a demanding glaze process to create Fairyland, an enchanting, and often strange, line of ornamental porcelain introduced in 1916.

As the upper middle-class daughter of an English country doctor, Susanna Margaretta (“Daisy”) Makeig-Jones did not follow societal expectations in Edwardian England when she pursued factory work. Though she had an artistic education, including schooling in London, it was highly unusual when she approached a family friend, Cecil Wedgwood, inquiring about a position at his family’s famous Wedgwood ceramic factory. Make-Jones joined the company’s training program for female painters in 1909 and became one of Wedgwood’s designers by 1914. Her imaginative and playful designs for Fairyland Luster were introduced two years later. Her fantastical world of charming imps and luminous fairies would have made a sharp contrast to the ongoing conflict of World War I in Europe. In the postwar years, Fairyland became so enormously popular that it revitalized the Wedgwood brand and lifted the ceramics company out of the wartime economic slump.

From its 18th-century origins, the Wedgwood factory had built its reputation on pairing technical innovation with savvy marketing. The company was founded in 1759 by Josiah Wedgwood, who transformed the cottage craft of his ancestor’s earthenware pottery into a grand manufacturing industry that still thrives today. In the late 1700s, Wedgwood innovated several types of new ceramics that were manufactured into a dizzying array of affordable, stylish dinnerware and ornamental pieces. This included the distinctive pale blue “jasperware,” usually overlaid with white ornament in a Neoclassical design that became synonymous with the name Wedgwood. In the 1910s and ‘20s, Fairyland Lusterware marked a striking departure from the company’s signature Neoclassical designs, but it shares the company’s emphasis on developing new ceramic techniques that align with current fashions.

As a work of technical innovation, Fairyland Lusterware advanced the “luster glaze” referred to in its name. Luster glazes have an iridescent surface of rainbow-hued metallics. These complicated colors come from the addition of metals—silver, platinum, copper, and/or gold—into the glaze recipe. These pots have been fired many times: first in the kiln to hold its clay shape, again for underglaze colors, and yet another round for an all-over, glass-like lead glaze. The pot was then fired multiple additional times to build up the metallic glazes for the flame, rainbow, and iridescent effects seen in Fairyland objects. Under Daisy’s direction, Fairyland Luster expanded the available palette of luster glazes, resulting in a time-consuming, highly crafted, and therefore expensive decorative technique.

Intricate with detail, Fairyland Luster presents a fanciful setting rich with characters and adventures like “Imps on a Bridge” or “Ghostly Woods.” Makeig-Jones details these stories in Wedgwood’s Some Glimpses of Fairyland, a 1921 publication that weaves tales by Hans Christian Andersen and the Brothers Grimm with fable’s of Daisy’s own making. Artistically, she incorporates inspiration from period fairy tale illustrations, including tribute to H.J. Ford’s The Colour Fairy Books (1889–1910), which Makeig-Jones had read to her siblings as a young woman.

NOMA has an impressive collection of twenty pieces of Fairyland Luster, the majority coming from a 2007 gift from Walda and Sydney Besthoff. NOMA’s collection of this turn-of-the-century porcelain is now on view in the second floor elevator gallery.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design