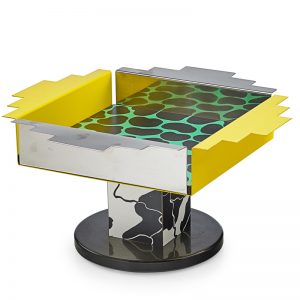

A display in the Lupin Gallery includes an array of twentieth-century decor: Frantz Industries (United States, Los Angeles, California), “Aero-art” Service Cart for DC3 Aircraft, 1938 design, Aluminum, Bakelite, rubber tires, Gift from the collection of Dr. Ronald Swartz and Ellen Johnson, 2018.52 • In style of Fredrick John Keisler (Austrian-American, 1890–1965), Floor lamp, 1930s, Chromed and enameled steel, Loan from the collection of Ellen Johnson and Dr. Ronald Swartz • Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, designer (German, 1886–1969) Knoll International (United States, East Greenville, Pennsylvania, founded 1938), MR Chair with arms, 1927 design, this version made c. 1980, Tubular stainless steel, cane seat, Gift of Dr. Donald R. Wood and John Webster Keefe in memory of Hans H. Lorenz, 99.83 • Sophie Taueber-Arp (Swiss, 1889–1943), Hans Arp, executed by (French, 1889–1966), Derniere Construction, 1942, Bronze, stainless steel, Edition 2 of 3, Gift of Mrs. Edgar B. Stern, 64.14.1–9 • Donald Deskey (American, 1894–1989), Table for Radio City Music Hall (New York), 1932, Chromed metal, lacquered wood, Loan from the collection of Ellen Johnson and Ronald Swartz

Led by a zippy Modernist bar cart and a barbed-wire cloud chandelier, NOMA’s design collection has entered the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries. The Lupin Foundation Decorative Arts Galleries on the museum’s second floor have reopened with a new installation drawn from the permanent collection, and for the first time include contemporary design and craft of recent decades.

Extending from the installation completed in 2017, which highlighted eighteenth-century Rococo and Neoclassical era objects from the Kuntz family’s foundational gift in 1978, the most recent Lupin Gallery installation begins with NOMA’s depth in the ornamented excess of nineteenth-century Victorian styles. This includes a luscious type of French porcelain, colloquially called “Vieux Paris,” or “Old Paris,” which was adored in the American South. “Old Paris” porcelains on view include some of the earliest pieces in NOMA’s collection, vases given in 1912 by founder Isaac Delgado, and extends through a collection given in 2015 by the Lupin family in honor of longtime collectors Dr. and Mrs. E. Ralph Lupin. This porcelain, and surrounding displays of glass, silver, and furniture reflect the Victorian embrace of ornament from previous eras, with designers reviving Rococo, Gothic, Classical, and Renaissance styles with a new gusto.

This exuberance is explored with a focus on “rustication,” a style that found popularity in the 1870s. This hyperrealistic ornament is found on famous Haviland plates from the 1879 White House service of President Hayes, which depict flora and fauna native to North America, but also on a mirror by an unknown maker boldly framed with twigs and carved animals. This rustication period includes nineteenth-century “Palissy ware” donated by actress Brooke Hayward Duchin. These ceramics are crawling with realistic molded fish, eels, insects, and shells in the manner of the Renaissance artist/scientist Bernard Palissy.

In the years preceding the pivotal turn of the twentieth century, many called for design to “reform” from the ornamented excess of the Victorian era. Those aligned with the Arts and Crafts Movement, Art Nouveau, and the Secessionists advocated for different aesthetics, but they united in calling for the production of higher quality objects for use in daily life. This included progressive designs by Christopher Dresser, Gustav Stickley, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and a focus on New Orleans’s contribution to design reform through works made at Newcomb College. Gorham Manufacturing Company’s silver Martelé production line shows a significant American contribution to the fresh Art Nouveau style in the gallery, thanks to gifts and select loans from Robert and Jolie Shelton. A dramatic staircase display shows a set of balusters designed in 1898 by Louis Sullivan for Chicago’s architecturally significant Carson Pirie Scott & Co. department store.

The rise of Modernist design in the 1920s eschewed all that came before, and in its embrace of new materials and factory production Modernism became the most influential design movement of the century. Rational design ideas included industrial glass technology applied to home goods, including Walter Dorwin Teague’s 1932 Lens bowl made at Corning from the mold for a locomotive engine light. New Orleans collectors Dr. Ronald Swartz and Ellen Johnson worked with the museum to augment this area of the gallery, including the gift of a charming lightweight aluminum and Bakelite Aero-art Cocktail Cart designed in 1938 for the DC3, the first airplane used for commercial passenger flights.

A wall hung with chairs designed by Ray and Charles Eames anchors the Midcentury Modern installation. Here, the rational impulses of Modernism softened in the postwar era to include rounded corners and a more playful sensibility, shown through iconic objects like Russell Wright’s “American Modern” dinnerware and in unique shapes like the timeless ceramics by the potter Katherine Choy, who led the ceramics department at Newcomb College in the mid-1950s.

For the first time in the museum’s history, NOMA now has a gallery dedicated to contemporary design. New acquisitions by design superstars Ron Arad and Marcel Wanders anchor this gallery, with Wanders’s barbed-wire cloud-like chandelier hanging above the exaggerated profile of Arad’s The Big Easy Chair. Important works of glass from all periods accent the Lupin Galleries. Recent glass works include household names like Dale Chihuly, as well as New Orleans’s own Gene Koss. Lynda Benglis’s only known work in the medium of jewelry is on view, a 1980s brooch designed for New Orleanian Jean Taylor, who gave the rare item to NOMA in honor of NOMA Director Emeritus John Bullard.

The new Lupin Galleries highlight connections between society and design, between craft and manufacture, and between fine art and functional household items. The galleries have an eye toward continual change, including the new Elise M. Besthoff Charitable Foundation Gallery which allows for rotations. The gallery now features a NOMA-commissioned artwork that combines several media. The Second Line Cocktail Service by international designer Geoffrey Mann is a glass cocktail service paired with an animated video that connects the design to the unique sounds of New Orleans’s Frenchmen Street. It is the work of computers and the work of ancient glass craft; it is of the world and of New Orleans. In the way it shows how objects reflect the culture of our lives, it is a thoughtful intellectual lens with which to view the entire new installation of decorative arts and design from the past three hundred years.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design