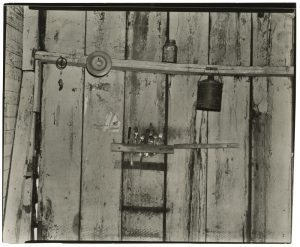

Walker Evans (American, 1903–1975, Kitchen Wall in Bud Field’s Home, Hale County, Alabama, 1936, Gelatin silver print, Image: 7 3/4 x 9 1/2 in. (19.7 x 24.1 cm); sheet: 7 7/8 x 9 5/8 in. (20 x 24.4 cm), Museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts Grant, 75.16

In December 2020, as NOMA explores concepts of ritual and gathering as a theme for the month, the Department of Photographs will share some images related to food and the rituals surrounding it. Not surprisingly, some of the most powerful photographs of these subjects focus on the scarcity of resources, especially those produced in the wake of the Great Depression in the United States. In the summer of 1936, Walker Evans and James Agee, on assignment from Fortune magazine, set out to chronicle the daily lives of typical sharecropper families in the American South. In Hale County, Alabama, they found three families—including the Fields—with whom they lived for a month, with Evans photographing and Agee writing about their lives and environments. Fortune ultimately rejected the article, but five years later their work was published in book form as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a sprawling but detailed, blunt but elegiac portrait in words and pictures of America’s rural laborers.

Evans took only two pictures of the interior of the Field’s home with his large view camera, and both are of the kitchen. This one, documenting the kitchen wall just above the table, is a lesson in practical necessity. Only the barest of essentials—kerosene can, churn top, Mason jar, and eating utensils—are presented against the backdrop of whitewashed boards. Each object occupies a purpose-built space. The unwashed bands on the wall trace the march of the flatware splint upward over the years, perhaps to keep pace with the growing children. Even the shaky structure of the cabin is revealed by the slivers of light entering the room from the exterior, in the lower left of the picture. Metal, paper, wood, and flaking chalk are all thrown into relief under the abrupt flash of Evans’s camera. Because whitewash was inexpensive and has slight antibacterial properties, it was common—especially in kitchens—in the homes of rural and urban poor alike. It was so popular that it became an icon of poverty, giving rise to the saying “Too proud to whitewash, too poor to paint.” In the Fields home, pride gave way to practicality, and the bright white boards gave Evans’s picture a direct, detailed, and clinical glow. Perhaps most importantly, Evans and Agee’s project threw light on the scarcity of food for those charged with growing it for others.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.