William Bradford, author, artist, and photographer (American, 1823–1892); John L. Dunmore, photographer (American, active 1860–1870); and George Critcherson, photographer (American, 1823–1892). The Arctic Regions, Illustrated with Photographs Taken on an Art Expedition to Greenland (London: Sampson Low, Marsten, Low, and Searle, 1873). Illustrated book with 141 albumen silver prints. Loan from the Collection of Stephen and Kitty Sherrill.

William Bradford, author, artist, and photographer (American, 1823–1892); John L. Dunmore, photographer (American, active 1860–1870); and George Critcherson, photographer (American, 1823–1892). The Arctic Regions, Illustrated with Photographs Taken on an Art Expedition to Greenland (London: Sampson Low, Marsten, Low, and Searle, 1873). Illustrated book with 141 albumen silver prints. Loan from the Collection of Stephen and Kitty Sherrill.

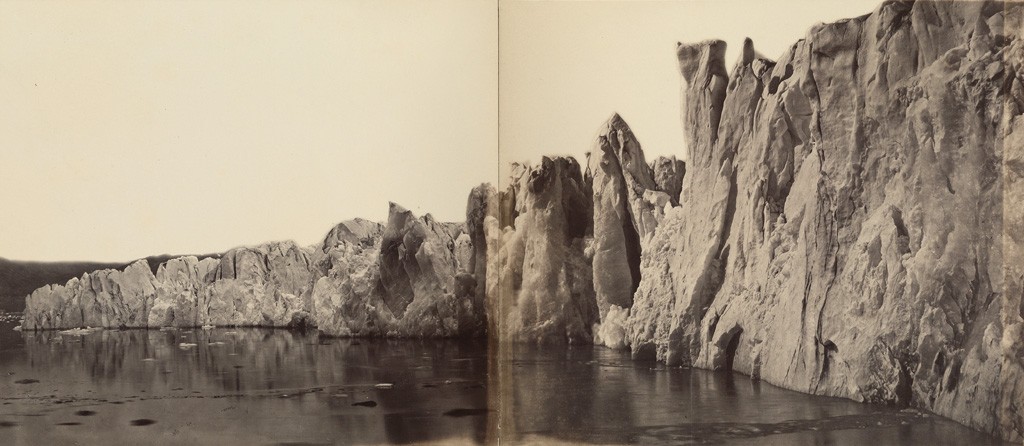

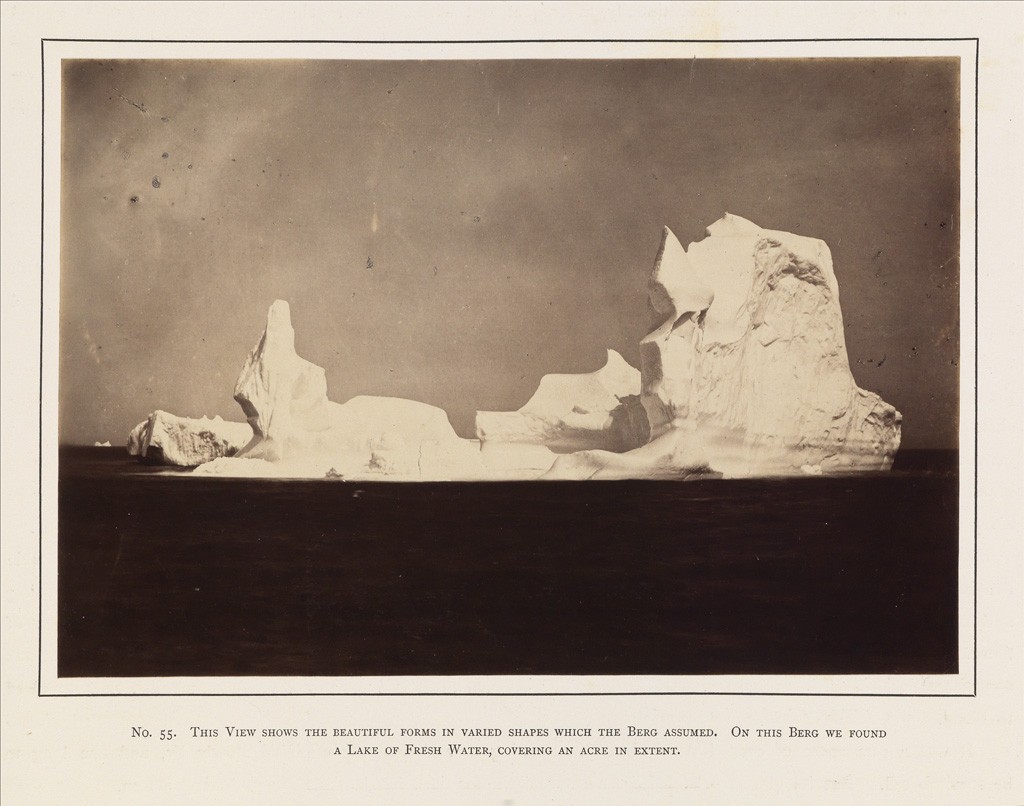

The images in this massive book were the first published photographs from the Arctic. In 1869, William Bradford, an adventuresome painter known for his Arctic seascapes and ship paintings, secured funding from businessman LeGrand Lockwood and chartered a steamship, The Panther, for a voyage to Greenland. He invited photographers John L. Dunmore and George Critcherson to join him on the expedition. During a three-month summer journey, the group produced drawings, texts, and photographs that were published in the lavish tome on display at NOMA in A Brief History of Photography and Transmission.

The brilliant gilt cover, complete with an icicle-clad title font and an image of a polar bear, indicates this object’s intended audience as the wealthy elite of the era. Published in 1873—four years after the journey and one year after the passing of their patron, Lockwood, to whom the book is dedicated—the book is a landmark in contemporary scientific inquiry, romantic landscape sentiment, and the history of photography. While quite novel at the time, the photographs have become important historical documents of a landscape that has changed dramatically over the course of nearly 150 years.

Although these photographs were not the first ever produced of the Arctic, they are the most accomplished and best-known. In fact, the very first photographs ever produced in the Arctic never even made it back home. On an American expedition in 1853, Amos Bonsall learned the difficult daguerreotype process and successfully produced a number of images on metal plates. According to his own memoirs, published some years later, he placed the finished daguerreotypes on a sled on the ice, but while distracted with other matters, the ice broke free and sled and photographs were carried away on a floe.

William Bradford, author, artist, and photographer (American, 1823–1892); John L. Dunmore, photographer (American, active 1860–1870); and George Critcherson, photographer (American, 1823–1892). The Arctic Regions, Illustrated with Photographs Taken on an Art Expedition to Greenland (London: Sampson Low, Marsten, Low, and Searle, 1873). Illustrated book with 141 albumen silver prints. Loan from the Collection of Stephen and Kitty Sherrill.

Following that first attempt, several other expeditions yielded successful photographs, but all of these were much smaller than the large images included in The Arctic Regions (some of which are almost 16 x 20 inches in size). In the 19th century, there were no photographic enlargers, so the size of the photograph was the same size as the negative, which in turn demanded a camera large enough to hold it. The crew of The Panther thus had to carry bulky equipment, jugs of chemicals such as collodion and silver nitrate, and a significant number of large glass plates to use for the negatives. Also, the photographic process at the time demanded that the negative be exposed immediately after it was sensitized and before the chemicals had fully dried (thus the term “wet-plate photography”). The cold Arctic air inevitably introduced challenges to a process invented in much warmer climes.

The pictures were undoubtedly a technical achievement, but it is important to note that, while many are beautiful, they were all produced in the course of an expedition whose implicit goal was to collect information about, and by extension conquer, the region. This ambition is underscored by the other kind of photograph included in the massive album: images of indigenous Inuit people and their lifestyles that are unflattering and often racist. These pictures, produced with a smaller camera, are interspersed amongst the text, and refer to the dirtiness and even “ugliness” of the “Esquimaux” peoples.

William Bradford, author, artist, and photographer (American, 1823–1892); John L. Dunmore, photographer (American, active 1860–1870); and George Critcherson, photographer (American, 1823–1892). The Arctic Regions, Illustrated with Photographs Taken on an Art Expedition to Greenland (London: Sampson Low, Marsten, Low, and Searle, 1873). Illustrated book with 141 albumen silver prints. Loan from the Collection of Stephen and Kitty Sherrill.

While we must continue to question the motives behind any 19th century project that explicitly claims to be about objective fact-gathering but never is, we can still find great importance in the documents that these projects left behind. Given our current understanding of the fragility of the Arctic ecosystem, these photographs, now almost 150 years old, trace a glacial landscape that is now only an historical phenomenon. The rapid pace of retreat for many glaciers means that the landscape today looks very different and will continue to change and threaten far away flood-challenged regions like Louisiana. These photographs may represent the past, but they are also reminders of how quickly we have arrived at the frightening present.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.