Historical Context for the Museo Egizio’s Collection and Queen Nefertari’s Egypt

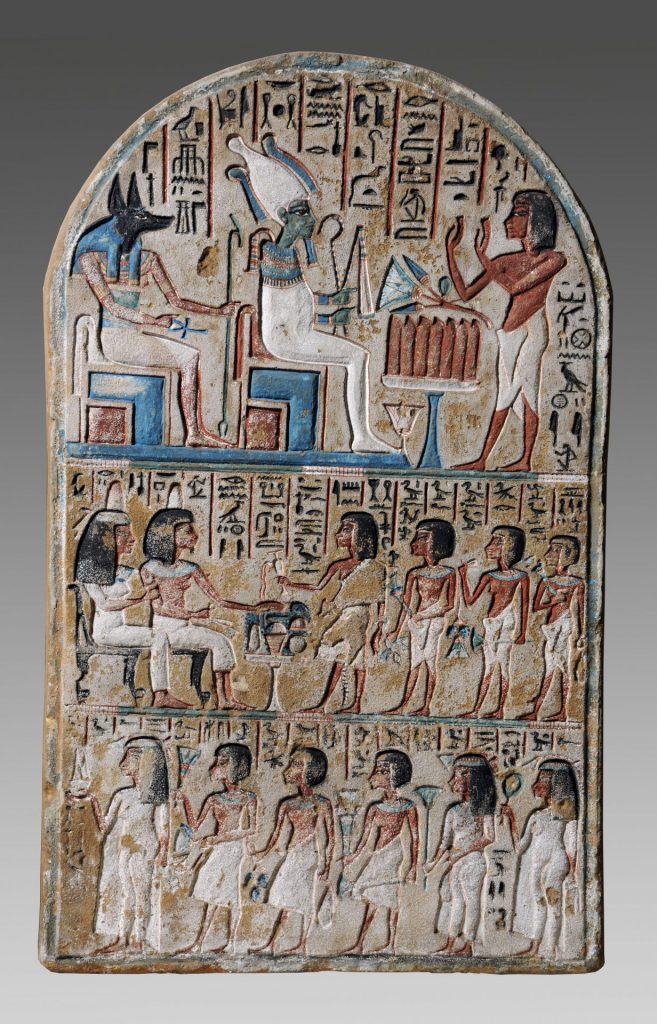

Stela of Nakhi, “Servant in the Place of Truth”, Offering to Osiris and Anubis. Sandstone. 39 1⁄3 x 24 3⁄4 x 6 inches. New Kingdom, late 18th Dynasty (c. 1300 BCE). Probably from Deir el-Medina. Museo Egizio, Torino.

Visitors to the New Orleans Museum of Art’s Queen Nefertari’s Egypt exhibition may ask, why do ancient Egyptian objects belong to an Italian museum? The brief history below seeks to locate the Museo Egizio’s collection within the larger context of European colonial history in Egypt and the circulation of ancient Egyptian art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

At the end of the eighteenth century, France sought to conquer Egypt in order to disrupt British trade routes with India and assert control over the Mediterranean. Napoleon Bonaparte, then a young general, led this invasion of Egypt in 1798. Napoleon brought with him not only 35,000 soldiers, but also more than 160 scholars, artists, and scientists whose research piqued European interest in Egyptian antiquities. While the French military occupation of Egypt did not last long, the invasion inaugurated the field of Egyptology and an intense competition among European powers to acquire these ancient Egyptian artifacts. The European-led excavations and trade in objects at the time were unregulated and often unscrupulous. The Museo Egizio in Turin (now part of Italy) was one of the beneficiaries of that competition; it received a large collection of Egyptian tomb objects from the King of Sardinia, who had bought them from the French consul.

In 1858, while Egypt operated as a semi-autonomous administrative division of the Ottoman Empire, the Viceroy of Egypt, Said Pasha, created the Egyptian Antiquities Service, and appointed a French scholar to direct it. (French scholars continued to direct the service for nearly one hundred years, until Egypt achieved independence from Britain in 1952. All subsequent directors have been Egyptian.)

In 1883, after British forces took control of Egypt in the Anglo-Egyptian War and established a de facto protectorate, the Egyptian Antiquities Service devised the system of partage, or division. This system gave Egyptian museum authorities first choice of the objects excavated by foreign-led teams and allowed the foreign archaeologists’ home institutions to claim the rest. An illegal, international trade in looted antiquities also continued.

At the start of the twentieth century, the director of the Museo Egizio, Ernesto Schiaparelli, sought to expand and contextualize the museum’s existing collection by conducting excavations in the vicinity of Thebes. With funding from the Italian king Vittorio Emanuele III and exclusive excavation permits from the Egyptian Antiquities Service, Schiaparelli established an official archaeological mission, which worked between 1903 and 1920 in eleven different sites, including the Valley of the Queens, where they rediscovered Queen Nefertari’s tomb, and the workmen’s village of Deir el-Medina. Under the partage system, the Italian mission was allowed to keep a part of the many thousands of objects they unearthed. The objects that you see in Queen Nefertari’s Egypt represent a selection of the Museo Egizio’s portion of the findings from Schiaparelli’s mission.

Prompts for Close Looking and Reflection

- Consider the artwork in Queen Nefertari’s Egypt within the context of colonial history. Why do you think nineteenth- and twentieth-century European powers were so interested in acquiring ancient Egyptian art?

- How might possession of ancient Egyptian works contribute to “soft” or non-military forms of imperial power in the fields of culture and science?

- What could be some of the consequences for modern Egyptians that so much of their ancestors’ artwork resides in museums in Europe and the United States and is claimed as part of a Western cultural heritage?

- Ancient Egyptians interacted with and participated in multiple cultural worlds: Nubia to the South, Libya and North Africa to the West, and the Levant or West Asia to the Northeast, in addition to the Mediterranean rim. How do you see the artwork in Queen Nefertari’s Egypt differently when you consider these other cultural contexts?

Sources and Recommendations for Further Learning

Queen Nefertari’s Egypt. Museo Egizio and New Orleans Museum of Art. 2022. (Exhibition catalogue)

Abd el-Gawad, Heba, and Alice Stevenson. “Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage: Multidirectional Storytelling through Comic Art.” Journal of Social Archaeology 2021, Vol. 21(1) 121–45. Online.

Atwood, Roger. “Insider: Guardians of Antiquity?” Archaeology. 61(4), July/August 2008. Online.

Cooney, Kara. Race and Ethnicity in Ancient Egypt, Colonialism and Ancient Egyptian Identity, Is Egyptology Racist? Short Answer: Yes. Videos available on YouTube and Facebook Live.

Molinero, Miguel Ángel. “Napoleon’s Military Defeat in Egypt Yielded a Victory for History.” National Geographic online. January 18, 2021.

Rocheleau, Caroline. “Golden Mummies: Reckoning with Colonialism and Racism in Egyptology.” North Carolina Museum of Art. June 8, 2021. Online.

Special thanks are due to the Portland Art Museum for creating and sharing this helpful resource for Queen Nefertari’s Egypt.