In 1914 President Woodrow Wilson issued a federal proclamation declaring the second Sunday in May as a national observance of Mother’s Day. NOMA honors the occasion by granting free admission to all moms on May 12, and Café NOMA will serve complimentary “Mom-osas” during brunch. The relationship between mother and child is sacred, and throughout history artists have sought to depict this bond in painting and sculpture. Raising a child is an art in itself, and we invite you to seek out these ten works of art that express motherhood, all of which are on view in the galleries and the Besthoff Sculpture Garden.

Cuzco School, Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, late 17th century, Mixed media over silver leaf on linen, Museum purchase and gift of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Q. Davis and the Stern Fund, 74.265

The Cuzco School, named for the Spanish colonial city in central Peru built atop a preexisting Incan capital, defines a genre of art created in the Andean highlands of South America. As Roman Catholicism spread across the continent from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, artists from multiple ethnicities created religious art. Here, the Virgin Mary is shown in resplendent robes, and two angels place a crown on her head, signifying Mary’s sudden transformation from an unremarkable Galilean Jewish girl into the mother of Christ upon the Immaculate Conception.

Attributed to Giovanni Del Biondo (Italian 1356–1399), Madonna Nursing Her Child, c. 1370, Tempera and gold leaf on panel, The Samuel H. Kress Collection, 31.1

Picturing the Virgin Mary nursing the Christ child is the oldest manner of representing the pair dating back to the third century. The tender act emphasizes the child’s fragile humanity as well as Mary’s status as compassionate advocate for mankind. The gold star on her shoulder is metaphorical and makes reference to the idea of the coming of the Christ child as the “bright star of dawn,” heralding a new age. In the middle ages, when Giovanni Del Biondo was working, upperclass women traditionally outsourced breastfeeding to wet nurses. Therefore, it is striking that he chose to depict the Virgo Lactans, or the nursing Madonna, as this acknowledges that Mary was not upper class, despite her revered status in Christianity.

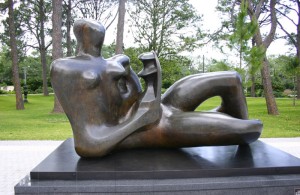

Henry Moore (British, 1898–1986), Reclining Mother and Child, modeled 1975, cast 1977, Bronze, Gift of the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Foundation, 98.141

British sculptor Henry Moore explored reclining figures and the relationship between mother and child in many of his pieces, a subject he considered universal “from the beginning of time” and “inexhaustible.” Abstractly rendered, this sculpture pulls the viewer’s focus to the parts of the figure that display femininity and fertility, such as her bosom and her full hips and thighs. The composition feels as if the viewer is intruding upon a private moment of physical connection. Though Moore was not given to psychoanalyzing his work, he once conceded that his choice of maternal subjects “could be explained as a ‘Mother complex.’ “

Alfred Boisseau (American, b. France, 1823–1901), Louisiana Indians Walking Along A Bayou, 1847, Oil on canvas, Gift of William E. Groves, 56.34

Alfred Boisseau was an Ohio-based artist best known for his depictions of Native Americans and the West in the latter half of the nineteenth century. His Louisiana Indians Walking Along a Bayou was displayed at the Paris Salon of 1848 and was declared the “grandest of all paintings of Southern Indians” at the time. Born and raised in France, Boisseau traveled to New Orleans while in his early twenties where his brother served as an assistant to the French consul. Each of the four Native American figures is seen in this painting carry an object: a firearm placed over the shoulder of the male at front, followed by a child grasping what appears to be a blow stick who precedes a stooped woman carrying a basket tethered to her forehead and, finally, a woman wrapped in a blanket carrying a sleeping infant. Louisiana is presently home to more American Indian tribes than any other southern state. Four federally recognized sovereign nations inhabit Louisiana, as well as ten tribes recognized by the state and four tribes without official status.

Domenico Beccafumi (Italian, Siena, 1484–1551), Venus and Cupid, c. 1530, Oil on linden wood panel, The Samuel H. Kress Collection, 61.73

In Roman mythology, Cupid was the son of Venus, the goddess of beauty and love, and Vulcan, the god of fire and a divine metalsmith who inhabits the underworld. Cupid gestures to his mother asking for the arrows she holds, which were made for him by Vulcan. Venus holds the arrows hostage as she gestures to the landscape explaining to her son the weight of responsibility possession of the arrows will bring, for his arrows strike immediate love in humans, nothing to meddle with or take casually. In the background, Vulcan is shown at work in his cavelike forge. According to legend, Cupid matures and falls in love with Psyche, a mortal woman who is compared to Venus and considered by some to be more beautiful than the goddess. Enraged with jealousy, Venus commands her son to kill Psyche, but in the process Cupid scratches himself with a bow and falls in love with his mother’s rival. The couple are able to overcome family strife, proving that love is possible in spite of maternal disapproval, but the lovestruck pair eventually face a crisis of trust when Psyche disobeys Cupid’s request that she never gaze upon his face.

Yoruba Peoples (artist unknown), Seated Mother with Child Divination Bowl (agere ifa), not dated, Wood metals, traces of kaolin, Gift of the François Billion Richardson Charitable Trust, 2015.38.71

The Yoruba are a west-African ethnic group centralized in Nigeria. They have a long tradition of seeing women as intermediaries between their physical and spiritual worlds. The figures topped with a receptacle is an agere ifa, or a bowl for sacred palm nuts used in divination rituals. The female figure is shown seated, with a child in her lap. The child is only marginally smaller than his mother, which highlights the child’s importance in relation to the mother. During the divination ritual, the diviners, known as Iyanifa (mothers who own Ifa) and the Babalawo (fathers of the secret) act as the intercessors between a Yoruba individual who seeks this guidance, and Ifa. Female diviners are not as numerous or as common as Babalawo in Yoruba communities. Generally, this is because few women are able to balance their domestic and maternal duties with their religious training. Thus, Ifanifa commonly choose to marry a Babalawo and practice in a partnership with them. The Yoruba people see the Iyanifa as the true caretakers of tradition, and for this reason only the Babalawo, who match their cultural knowledge and influence are worthy of marrying them.

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926), Mother and Child in the Conservatory, 1906, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase with funds contributed by gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harold Forgotston, 82.124

Mary Cassatt was an American painter who lived and worked for most of her career in France, where she developed a close relationship with Edgar Degas and other Impressionists. Though daringly independent in her years as a young artist and never married, in her early 30s Cassatt was forced to care for her ailing sister and lived with her parents. She turned her attention to domestic scenes and became best known for her depictions of the private sphere of women, with special emphasis on the intimate bond between mothers and children. Unlike most portraiture of the time, most of Cassatt’s paintings were not commissions. She often used models and, on occasion, friends or working women to portray the mothers, and the children were not the real child of the “mother” in the painting.

Art Shay (American, 1922–2018), Hula Hoop Fun for the Whole Family, c. 1960, printed later, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Stephen Daiter Gallery, 2012.4

This scene of women and children in suburban Chicago hula hooping at the height of the novelty craze is among the photographs on display in the exhibition You Are Here: A Brief History of Photography and Place. The photographer, Art Shay, was a writer for Life magazine from 1947 to 1949, and thereafter settled in Chicago where he became a freelance photographer, landing thousands of assignments for Life, Time, Sports Illustrated and other national publications. He spent decades covering the streets of America’s “Second City,” assembling a portfolio of the metropolis throughout the latter half of the twentieth century. Of this amusing assemblage, Shay said, “When the hula hoop craze hit, I was assigned by Life to do the Chicago segment. This picture was taken in 1959 in front of our house in Deerfield. I gathered all the neighbors I could. [My wife] Florence, in the white shirt, is at the top right. The little girl [at her left], our daughter Lauren, is now a grandma. It didn’t run in the magazine, though; Life chose my picture of a big fat guy in the Loop with a hula hoop.”

Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825), Murder of Geta, c. 1782, Gray ink and wash on paper, The Muriel Bultman Francis Collection, 86.177

This ink drawing is on view in the exhibition Paper Revolutions: French Drawings from the New Orleans Museum of Art. Roman Empress Julia Domna (AD 160–217) clutches her dying son Geta as his brother Caracalla commits fratricide. Unlike most imperial wives, Julia remarkably accompanied her husband, Septimus Severus, on his military campaigns and stayed in camp with the army. For her devotion to Rome, honorary titles were granted to Julia, including mater castrorum, mother of the camp, and mater patriae, mother of the fatherland. Her sons feuded after the death of their father in 211 over inheritance of the empire, resulting in Geta’s murder and the massacre of an estimated 20,000 of Geta’s supporters. After the assassination of Caracalla by a Roman solider six years later, Julia Domna committed suicide.

Baule Peoples, artist unknown, Côte d’Ivoire, Spirit Spouse (asye usu), not dated, Wood, glass, Bequest of Victor K. Kiam, 77.238

The Baule people live in Africa in Ghana and the Côte d’Ivoire. They have a long tradition of mask and figure carving that intertwines their spiritual and physical worlds. This statue represents a Spirit Spouse, or a representation of a deceased spouse. This statue depicts a woman, and would have been kept by her widowed husband as a representation of her. The statue honors the life and purpose of the woman. It has exaggerated sex characteristics and a child strapped to its back that indicate fertility and, consequently, motherhood. This statue represents how the woman’s role as a mother continued throughout her life and into her afterlife.

Editorial and design intern Emma Coffman contributed to this list of works in NOMA’s permanent collection.