Gordon Parks famously stated that photography was his “choice of weapons” against racism, intolerance, and poverty. While photographs have certainly been used to document and advance social justice causes in the past, the use of photography in recent protest movements has demonstrated one of the dangers of the medium. While protest photographs have amplified these movements’ messages and visibility, those very same photographs have been used against their makers by other authorities.

The present moment requires that we consider how the digital, social world has made photography an instantaneous and global “weapon” that can slip easily from one hand to another. The following group of works—which are all currently on view in NOMA’s exhibition A Brief History of Photography and Transmission—invite us to consider how photography has been used in this context through historical and current examples.

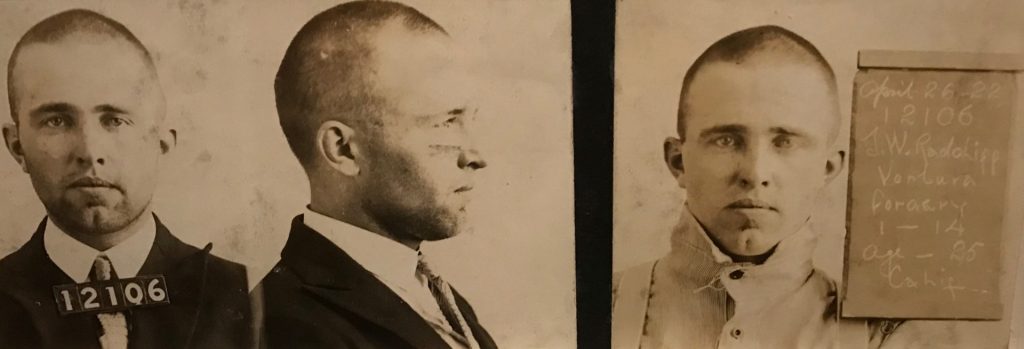

Unidentified photographer (American, 20th century), Mug Shot of J.W. Radcliffe from Folsom State Prison, c. 1922. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Craig Dietz, 94.42.1.

Mug shots are only one instance of the global systematic use of photography in incarceration and surveillance. Law enforcement adopted the classic frontal and profile views from racist, nineteenth-century ideas about the relationship between physiognomy and moral or mental capacity. The first two pictures in this group appear to have been taken at the moment of Radcliffe’s arrest (for forgery), but the third was clearly produced at Folsom, judging from the prisoner’s attire. It is important to remember that photography, in this context, is devoted to the cataloging and control of the subject. To put it another way, the historic use of photography as an incriminating tool is a one-sided story: Regardless of their innocence or guilt, the subject of these kinds of photographs is denied any agency in the picture-making process.

Alejandro Cartagena (Mexican, born 1977), Insurrection Nation, 2021. Staple-bound printed volume on paper (detail). Museum purchase, E-2021-10.1.

Facial recognition technology in photography is now commonplace. Some of us might have had our phones or photo-storage apps recommend the identity of someone in our photographs based on this technology, for example. While there are countless examples of the ways in which law enforcement has used this technology to target protesters of social causes, artist Alejandro Cartagena appropriated the same technology to produce his Insurrection Nation, a magazine that consists of nothing but close up, internet-sourced images of the faces of those who participated in the attack on the US Capitol on January 6 of this year. Compiled, designed, and printed within thirteen days of the insurrection, Cartagena’s limited-edition magazine demonstrates that anybody can invoke these technologies very quickly. Most of the photographs that Cartagena included in his magazine were taken by the insurrectionists, and proudly posted in very public digital places. The simple act of gathering these images is therefore akin to allowing the criminals to incriminate themselves.

Abdul Aziz (American, born 1978), Untitled (Dawn), 2020. Pigmented ink print and commercially produced color print. Museum purchase, Tina Freeman Fund, and gift of the artist, 2020.23 and 2020.24.

More recently, independent photojournalists such as Abdul Aziz have reclaimed authority over photography, and the stories that it tells. This past year, he documented the Black Lives Matter protests in New Orleans that took place in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. In this image, Dawn defiantly stands her ground. Shot over the shoulder of law enforcement, and through their shields, the photograph emphasizes the crowded, tension-filled moment.

While many of Aziz’s photographs have had almost instantaneous impact and widespread exposure digitally, this image had almost immediate impact as a physical print. A print of this image was produced under Aziz’s supervision and placed on view in an exhibition just ten days after the picture was taken. That exhibition, No Justice No Peace: Portraits of Resistance, was organized by Leslie-Claire Spillman and was on view at The Front June 13–July 5, 2020. A few months later, a larger print was produced by Leona Strassberg Steiner to Aziz’s specifications.

While the larger size is important in terms of its display in a museum, where it visually challenges large paintings in adjacent galleries, the existence of both prints demonstrates photography’s possibilities for replication and distribution, which have allowed for activists to have a greater voice and visual presence. Aziz’s work helps restore the balance of power in the use of photography, taking a tool that was once only in the hands of white authority and employing it to produce positive images of the power of Black communities.

For more on the rapidly developing field of ethics in protest photography and photographic technology, please watch a panel discussion that NOMA hosted on these topics with Caroline Sinders, Brian Palmer, and Tara Pixley.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints and Drawings

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.