As NOMA explores the theme of process and materials, this essay looks back at an exhibition from 2011, What is a Photograph?, and some of the treasures that it included from the museum’s collection.

What is a photograph? How do we define its history? Over the past 190 years, photography has infiltrated almost every aspect of modern life, from birth to war and science to religion. During this time, the photograph has taken many forms, including the daguerreotype, cyanotype, and gelatin silver print. Scholars and historians have often found it difficult to write a history that gives equal weight to each of these distinct forms, but recent technical developments in photography have made it even more complicated. With the advent of the digital era, it seems that photography’s history must be expanded to include not only images on metal plates, paper, and cloth, but also images on laptop screens and handheld devices, images that may never physically exist at all. It has become clear that a history that narrowly defines photography as one medium is insufficient. Photography, it seems, is not one medium, but many.

What is a Photograph? included and described many of the most common photographic processes, but it also included objects, artifacts, and practices that have typically been considered marginal to the history of photography, such as reproductions of photographs in ink, negatives, cameraless photographs, cartes-de-visite, color processes, and even a piece of jewelry. These disparate works invited visitors to consider what—if anything—links them together within the history of photography. The selection below highlights some of the more unusual, and often unique, objects in the museum’s collection.

Richard Beard (British, 1801-1885), Cut-paper silhouette of a man, ca. 1853, Quarter-plate daguerreotype in leather case with gilt tin mat, Museum purchase, Tina Freeman Fund, 2012.83

The daguerreotype, a process perfected by Louis- Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and named after him, was the first photographic process introduced to the world in 1839. A daguerreotype consists of a layer of light-sensitive silver iodide on a highly-polished sheet of copper that was developed with mercury vapors. The image that results is actually a negative and appears as a positive only because of the reflective surface of the copper plate. Each daguerreotype is unique: the object you see here was inside the camera as it was exposed to the cut-paper silhouette. It may seem strange to record one unique object with a process that creates another, but there is a parallel between the silhouette and the daguerreotype, as the latter ultimately replaced the former as the preferred popular portrait phenomenon.

In the nineteenth century, portrait photographs often served as memorial devices, preserving the memory of a specific individual. In this case, a daguerreotype portrait of a recently deceased young girl has been incorporated into a mourning bracelet probably made for the child’s mother. The girl’s portrait is tucked away on the back of a medallion which, on the other side, presents her initial and a decorative border of flowers—all carefully constructed from the child’s hair. Even the bracelet band is formed from hair woven so tightly that it resembles thread. While this may seem bizarre to a modern viewer, the piece fits into a long tradition of collecting locks of hair as a reminder of the departed, which stemmed from the belief that hair was the most enduring and immortal part of the body. Combining the physical specimen of hair with the ephemeral qualities of the daguerreotype, the bracelet becomes an almost talismanic memorial. The unusual orientation of the daguerreotype, on the inside of the bracelet, means that the image of the young girl would have literally touched the mother each time she wore it, a particularly intimate detail in a piece defined by mortality.

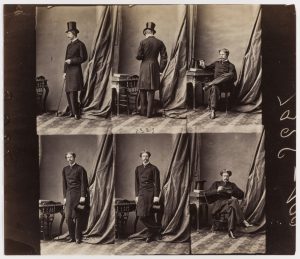

André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (French, 1819-1889), Monsieur Van Sittart, 1861, Albumen print, Museum purchase, Carrie Heiderich Fund, 96.19

The photographic carte-de-visite was patented by Disdéri in 1854 in response to the desire for affordable portrait photographs. Disdéri had a special camera made with a mobile chassis that allowed for several exposures (in this case six) on a single glass plate negative. That negative could then be printed onto one sheet of albumen paper, producing an oddly cinematic progression of pictures. Whole sheets like the one shown here are relatively rare. Typically these sheets were cut up and mounted on stiff cards. These small cards were a play on the traditional engraved calling card, objects that would be exchanged with friends or acquaintances during social events. Eventually it became just as common to collect cards of celebrities—singers, royalty, artists, etc.—as it was to have your own portrait carte.

The camera is often considered an essential part of photography, but an entire history of cameraless photography can be traced from the origins to the present. It begins with many of the earliest photographs, which were simply specimens placed on the surface of photosensitive paper, it includes things like the drawing/printmaking/photography hybrid cliché-verre process, and it flourished in the modernist moment when many artists experimented with photogram processes.

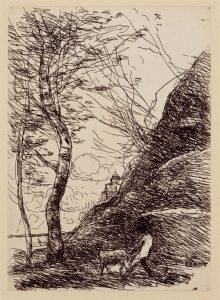

Jean Baptiste Camille Corot (French, 1796–1875), Shepherd Struggling with His Goat, 1874, Albumen print from a cliché-verre negative, Museum purchase, Friends of Prints and Drawings, 2003.72

Cliché-verre negatives are created by covering a glass plate with a dark resin and then scratching through the resin with a burin to create a design. This exposes the bare glass and creates a photographic negative that can be used to print multiple copies of the drawing. The cliché-verre process is therefore a hybrid one, resulting from the combination of photography and drawing. The painter Camille Corot learned how to make cliché-verre negatives from a photographer, Adalbert Cuvelier, who worked alongside Corot in the Forest of Fontainebleau in France.

Maurice Tabard (French, 1897–1984), Jazz, 1929, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, 1977 Acquisition Fund Drive, 77.44

This photogram was used as the cover for the November 1929 issue of the monthly art and literary review Jazz: L’Actualité Intellectuelle. Despite its brief run—it survived for only fifteen issues, from December 1928 to March 1930—the magazine presented the work of an incredibly diverse group of writers, artists, photographers, and designers, including André Kertész, László Moholy-Nagy, Jean Cocteau, Man Ray, Joseph Conrad, Max Jacob, and Berenice Abbott. Jazz was particularly progressive for its use of avant-garde photographic practices, such as the cameraless photogram technique that Maurice Tabard used to create the present work; here, the shadows cast by objects, which have been placed directly on the photographic paper, appear as stark white graphic forms. The process was especially well suited to a journal whose namesake—jazz music—privileged improvisation and chance: the position of the objects on the page and the objects themselves—comb, razor, compass, and so on—express an overriding randomness, as if the objects selected themselves and then tumbled on to the paper with only the laws of physics dictating their final placement.

Andreas Müller-Pohle (German, b. 1951), Digital Scores VII (after Nicéphore Niépce), 2012, Pigmented inkjet print, Museum purchase, Tina Freeman Fund, 2012.82

The advent of digital photography in the 1990s provoked discussions about the fate of photography. Some scholars and critics began to lament the “death” of photography, arguing that digital technology was something fundamentally different. But processes and practices come and go throughout photography’s history as if to suggest that the only constant in its history is change. Seen in this context, digital photography is but another iteration in an ever-evolving field of visual image making. Over the past twenty years, many artists have produced works that address the history of the history of photography, reinterpreting works from

the past or commenting on certain principles that have been central to photography.

Andreas Müller-Pohle, for example, produced a truly digital version of the world’s oldest known camera image. Müller-Pohle has transcribed Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras (1826/27) into its digital code, presenting the world’s oldest known camera image in a very different language. True to its title, this work is like a musical score, if fed into the right translation device, Niépce’s image would appear in its more familiar form. By obscuring the original image, Müller-Pohle’s piece mirrors the early history of photography, much of which remains mysterious as a result of lost artifacts, or nearly invisible early images.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.