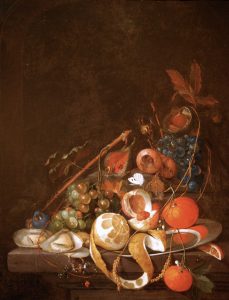

Cornelis de Heem (Dutch, 1631–1695), Still Life with Fruit on a Ledge, Oil on canvas, 26 1/2 x 21 1/2 in., Gift of the Azby Art Fund in memory of Herbert J. Harvey Jr. and Marion W. Harvey, 83.50

After gaining independence from Spain in the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic became one of the greatest economic powers in Europe. Cosmopolitan cities like Amsterdam, Leiden, and The Hague were increasingly populated by wealthy bankers and merchants who profited from an era of booming international trade spurred by colonial conquests. Dutch artists responded to the demands of this new moneyed class of patrons by painting portraits, still lifes, and seascapes, representing the riches of the Dutch maritime empire.

The hallmark characteristic of seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes is a closely observed illusionism wedded to moralistic content. An excellent example is provided by Cornelis de Heem’s Still Life with Fruit on a Ledge, both a dazzling display of technical accomplishment and a rich repository of allegorical significance. The complex overlapping arrangement and consistent tonal quality produce an emphatically unified composition.

Orange peels and wheat stalks spill over the ledge, lessening the gap between the pictorial space and the viewer’s space, and thus beckoning the viewer to contemplate the significance of the message. Inviting on the outside, but sour on the inside, the lemon is a symbol of the luxury which alienates man from God. De Heem has juxtaposed elements with good associations and those with bad to remind the viewer of the choice between earthly pleasures and heavenly reward. The oyster, long considered an aphrodisiac, is a symbol of lust while both the lemon and the orange may refer to original sin. The butterfly represents the human soul and its possibility for redemption, while the collection of fruits and nuts refers to the Passion of Christ, which gave humankind this possibility.

Finally, the grapes and wheat are symbolic of the Eucharist. A vanitas message, or reminder of the transience of human life, is conveyed by the perfectly ripe state of the organic objects, which will soon decay, alluding to the erosive character of time. While de Heem’s painting is an opulent display of luxurious objects, it reminds the viewer that these are ephemeral pleasures and thus admonishes moderation.

This Object Lesson, written by Sharon E. Stearns, is excerpted from the New Orleans Museum of Art Handbook, available for purchase in the Museum Shop. De Heem’s painting is on view among other works of the Dutch Golden Age on the first floor of the museum.

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.