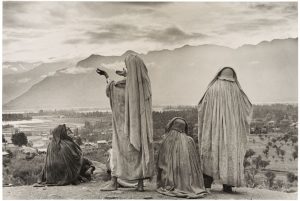

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908–2004), Srinagar, Kashmir, 1948, Gelatin silver print, 9 9/16 x 14 3/8 in. (24.3 x 36.5 cm), Museum purchase, Women’s Volunteer Committee Fund, 73.222

Here, a group of Muslim women pray on Hari Parbat, a holy site overlooking the Indian city of Srinagar, while the sun rises behind the Himalayas. The hill is a nexus point for many religions: a Hindu temple, multiple mosques, and gurdwara (places of assembly and worship for Sikhs) are all located there. Isolating the group of figures against the mountains, Henri Cartier-Bresson arrested the moment when one of the women reaches out, a gesture of prayer that looks as if she is releasing the distant clouds into the air like doves. A month after making this picture, Cartier-Bresson met with Mahatma Gandhi to cover the breaking of his six day fast, and ninety minutes after that meeting, Gandhi was assassinated.

The word “immediacy” is often invoked in discussions about photography. It is frequently found as a descriptor for the work of Cartier-Bresson, and perhaps this is not surprising: “immediacy,” used loosely, connotes the same sense of urgent temporality as does the famous “decisive moment” conception of photography that is usually applied to Cartier-Bresson’s work (despite the fact that he never used the term to describe it). Used precisely, however, “immediacy” refers to something that is unmediated, a direct engagement with a thing or an experience. As convincing as any photograph of a thing might be, it is still a mediated version of that thing, which is to say that a photograph might seem to possess a sense of immediacy, but that perception is nothing but an alluring deception.

Consider the present image, for example. Let us assume for a moment, even if it is not true, that we know nothing about it. Then let us consider the distance between what little we can know for certain from the image and how much more we would know if we were actually there. We can make several assumptions about the isolated moment that the photograph represents, but it lacks the before and after that actual experience would provide. In this case, for Cartier-Bresson, that experience included the beginnings of the Indo-Pakistani War; arduous travel by boat, plane, train, bus, military convoy, and foot; and days of rain and flooding. It was, in other words, much noisier and more violent than the quiet, contemplative image that he managed to excise from that experience would suggest—here, a group of Muslim women pray on Hari Parbat, a holy site overlooking Srinagar, while the sun rises behind the Himalayas.

Of course, Cartier-Bresson never intended for his photographs to fully articulate their own contexts; rather, his goal was to make pictures, like this one, that can convey a sense of humanism beyond the facts that brought his images into being. While this photograph may remain mute as to the social and political backdrop of its subjects, Cartier-Bresson’s intuitive attention to the alignment of elements in front of the camera results in a picture that is rich with suggestion.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

Your gift to NOMA provides critical support for the museum and plays an integral role in all that the museum does, from presenting groundbreaking exhibitions to offering arts-integrated education programs to students across the region.