This week, as NOMA turns its focus towards themes of connection, we are thinking about how human relationships shape artists’ careers, and how we can use those connections to interpret different artworks. In Mexico City during the 1920s and ‘30s, art flourished and grew thanks to the creative, romantic, and political relationships between artists in that city. NOMA’s permanent collection includes works by several of these pioneers of Mexican modernism. Two names in particular—Tina Modotti and Lola Alvarez Bravo—stand out as two of the most important photographers of this period, even as their work has long been unfairly overshadowed by that of their male partners. For several years in the 1920s Modotti and Bravo were friends and traveled in social circles that included Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Rufino Tamayo, among others. The two photographers even shared ownership of the same Graflex camera, which enabled each of them in turn to achieve new heights as artists. Because the photographic act can require two or more participants—on either side of the camera—photographs can be profound objects through which to consider the importance of human connections in art.

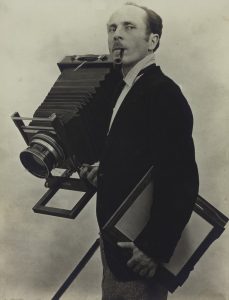

Edward Weston (American, 1886–1958), Tina, 1924, printed later, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Justin Hanaw, 74.80

Tina Modotti moved to Mexico City in 1923 where she was soon joined by her creative and romantic partner Edward Weston. Modotti spoke fluent Spanish and managed the business side of their portrait studio. They also made many photographs together. These two portraits (among dozens that they took of each other) suggest something about the artists’ personalities. Weston poses confidently – perhaps in a self-aggrandizing way – proudly bearing the tools of his trade. Modotti very much served as Weston’s muse, and his portrait of her closes in on Modotti’s face. She appears wistful, and as if she may be singing or speaking. Weston’s portrait of Modotti is romantic with soft edges; Modotti’s picture of Weston (below) is precise and realistic. It would be overreaching to state that these two pictures, made a year apart, fully encapsulated Modotti and Weston’s relationship or the differences in their approach to photography. They can, however, encourage us to think about how a portrait is itself evidence of a human connection, that tells us how the portrait-sitter wished to be portrayed in that moment, but also how the photographer understood the person in front of the camera.

Tina Modotti (Italian, 1896–1942), Portrait of Edward Weston with a Camera, 1923, Gelatin silver print, Museum Purchase, Women’s Volunteer Committee Fund, 74.31

In addition to their portrait work, Modotti and Weston traveled the Mexican countryside. Modotti’s camera was especially drawn to the land and folkways of her adopted home, interest concern that translated into deep concern for the struggles of the working class and increasing anti-fascist activism. When Edward Weston returned to California in 1926, Modotti found space to pursue these issues more fully in her photography. About the same time, she acquired a Graflex camera, a lighter hand-held model that allowed her to move freely on the street and among the people of Mexico.

Photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo later identified the year 1926 as a split in the aesthetics of Modotti’s work. He described the first three years of her time in Mexico as her “romantic” period, but from 1926 to 1929 she became a “revolutionary” photographer. Her photography reflected her concerns for human rights and the working class, often drawn through agrarian themes and markers of Mexican cultural identity. In 1930, following allegations about her involvement in the murder of her then-partner Julio Antonio Mella, Modotti was deported by the Mexican government. Short of cash, she sold her Graflex camera to her friend Lola Alvarez Bravo, who was herself a burgeoning photographer beginning to strain under the control of her husband Manuel.

As it had for Modotti, the Graflex freed Lola Alvarez Bravo from the confines of the studio. Bravo’s photographic interests also centered on the working and cultural lives of people in Mexico City. Her new camera allowed her to work more quickly and without the obtrusiveness of a tripod and viewing hood that a large-format camera required. By 1934, frustrated in part by her husband’s reluctance to allow her independence with the camera, Bravo left the marriage. She quickly found success in editorial and journalism assignments but continued to pursue her own personal vision. She excelled at composition and her use of light and shadow, creating crisp and clear pictures that reflected her interest in the everyday lives of Mexican people.

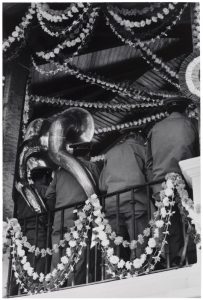

Lola Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1903–1993), Sin Titulo, c. 1950, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, General Acquisition Fund, 82.64

By mid-century Mexico was undergoing tremendous change, as the country industrialized and many people moved from rural to urban areas. These tensions are especially reflected in Bravos’ frantic (and underappreciated) photo-collages, but also in many straight photographs like this one, in which she overlays a number of competing lines to create a feeling of excess, energy, or even confusion. Bravo’s vantage for taking this photograph of a quartet of brass musicians is inspired, and in keeping with her focus on everyday people. Rather than photograph from the heights of the stage, or even the unobstructed front row, she chose a viewpoint that is decidedly “backstage,” or where the nitty gritty of pulling a concert together really occurs. She also elevates the musicians, the cultural workers, doing the very labor of bringing people together for some kind of shared connection. This is a photograph and an attitude that should be familiar to New Orleanians, and one that, arguably, Modotti would have enthusiastically embraced as well.

—Brian Piper, Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Photographs

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.

▶ DONATE NOW