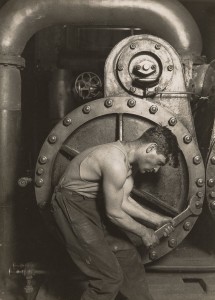

Lewis Wickes Hine (American, 1874–1940), Mechanic and Steam Pump, 1920, Gelatin silver print, Image: 9 1/2 x 7 in. (24.1 x 17.8 cm); sheet: 10 x 8 in. (25.4 x 20.3 cm), Museum purchase, 74.84

The story behind the making of this photograph is a lesson in how photographers craft stories into pictures. Lewis Hine, who was well known for this ability once said, “If I could tell the story in words, I wouldn’t need to lug around a camera.”

Some great photographs are the product of circumstance: the right time of day, the right gestures, and the right vantage point, for example, collapse into a single moment that the photographer is lucky enough to witness. Other photographs, even those that masquerade as documents, are the result of persistence, lengthy experimentation, and the concerted imposition of the photographer’s will. Hine’s image of a steam pump mechanic is an example from the latter group. Over the course of a photography session with mechanics of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Hine produced several negatives of different men posing with different machines before he apparently settled on the handsome, powerful model in this image. Even then, however, Hine made slight adjustments to the mechanic’s pose and the camera’s position. The result is a series of variants, some of which are so similar that they have often been used interchangeably as “the” iconic image. The present picture, for example, is not the one that was most often chosen by Hine for reproduction—in his favorite, the mechanic’s arms are slightly more extended and his head leans further forward—and yet it could easily be mistaken for it. The artifice of both images is apparent—the wrench’s grip on the bolt is poorly suited to the task of tightening—but as representations of “powermaking,” the pictures are unparalleled, with arms echoing spokes and muscles, bolts. Since both pictures achieve Hine’s goal of championing the symbiotic relationship between man and machine, positioning the modern worker as an essential and forceful wrangler of industrial production, perhaps there need not be only one chief image.

Hine first published the other version in “Powermakers: Work Portraits by Lewis W. Hine,” an article in which he equated the role of the railroad workers with that of ancient horse groomers and caretakers, responsible for the harnessing of “ten thousand horse-power.” Since then, it or the version reproduced here has been widely published and even imitated or altered in images circulated on the Internet. The mutation from a singular image to a series of images demonstrates how photography is often more strongly tethered to an idea than it is to a particular moment in time. Hine was an active proponent of this argument, referring to his practice as “interpretive photography” in stamped credits on the backs of his prints. His understanding of photography’s conceptual possibilities allowed him to create multiple successful photographs in this project that today form an iconic collective, a series of closely related images that enter our consciousness as powerful illustrations of an idea that Hine meticulously crafted into pictures.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.

▶ DONATE NOW