Bror Anders Wikstrom, Design for “D – Dragon” float in “The Alphabet” parade, Krewe of Proteus, 1904. Carnival Collection, Tulane University Special Collections.

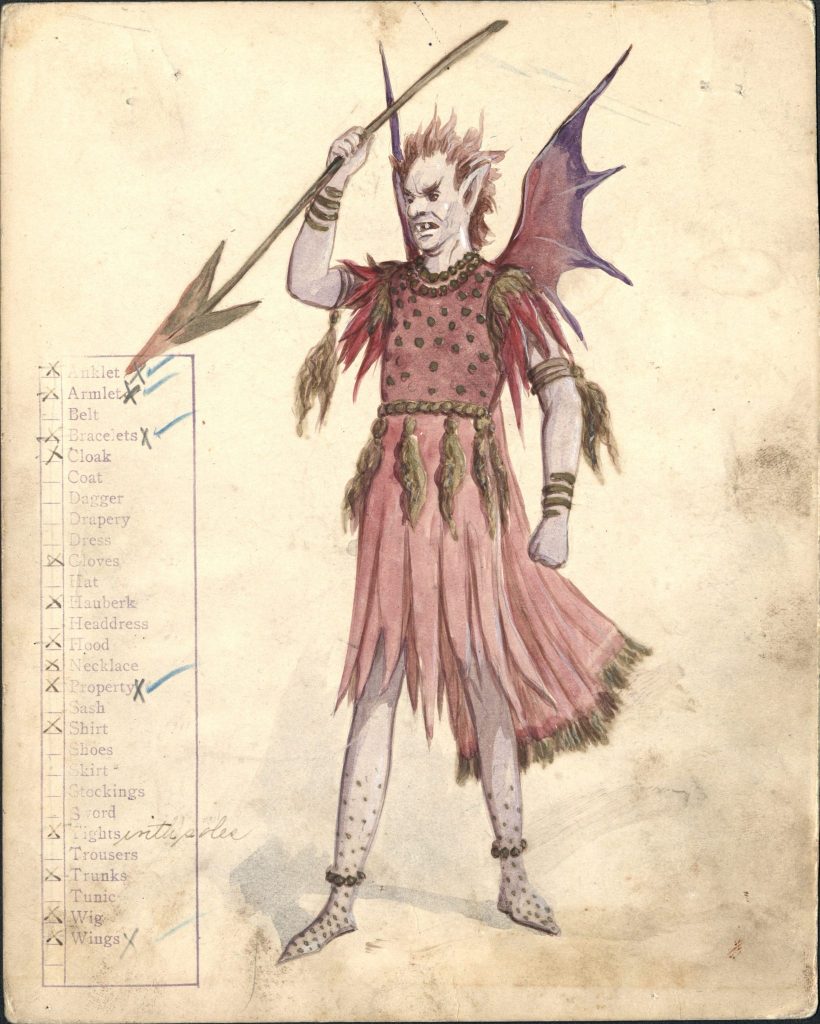

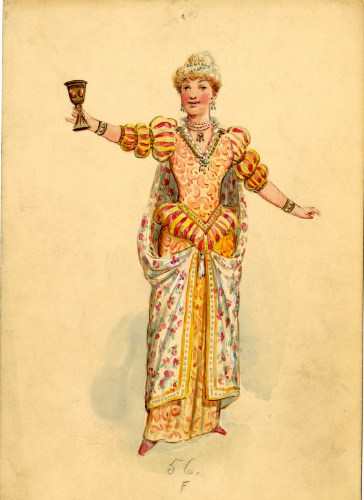

Bror Anders Wikstrom made a name for himself in New Orleans by engaging with the heart of the city’s creative culture: Mardi Gras. Wikstrom was the chief designer with the Krewe of Rex from 1885 to 1910, putting his fantastical designs at the formative decades of the New Orleans artistic street party now known around the world. He imagined wild designs for the grand pageantry of tableau parades, from the courtly regalia of old-line krewes to the whimsical fairies and creatures that bring joy, and maybe some naughtiness, to Mardi Gras celebrations.

With watercolor washes and metallic details, Wikstrom’s sketches were the starting point in bringing otherworldly stories to life on the streets of New Orleans. Literary and fantasy parade themes like “The Freaks of Fable” or “A Trip to Wonderland” became moving pageants of elaborate floats populated with dramatic costumed characters. Many New Orleans art collections house Wikstrom’s original designs including his early sketches, final design presentation plates, newspaper parade bulletins, and the vintage street photography that shows how these creations looked rolling through the crowds on Mardi Gras day. The New Orleans Public Library and The Historic New Orleans Collection have notable collections, with the largest trove housed at Tulane University’s Carnival Collection.

Unknown photographer, View of street showing Float #10 “Uneasy the Head the Wears the Crown,” Krewe of Rex, 1902. Carnival Collection, Tulane University Special Collections.

A Swedish émigré to the United States, Bror Anders Wikstrom (1854–1909) went to sea in his youth, studied art at the Royal Academy of Stockholm and in Paris, and eventually found his way to New Orleans by 1883. By the time of the Cotton Centennial of 1884, the artist was active in the New Orleans artistic community, first working as an assistant to fellow Swede Charles Briton, a well known Mardi Gras designer.

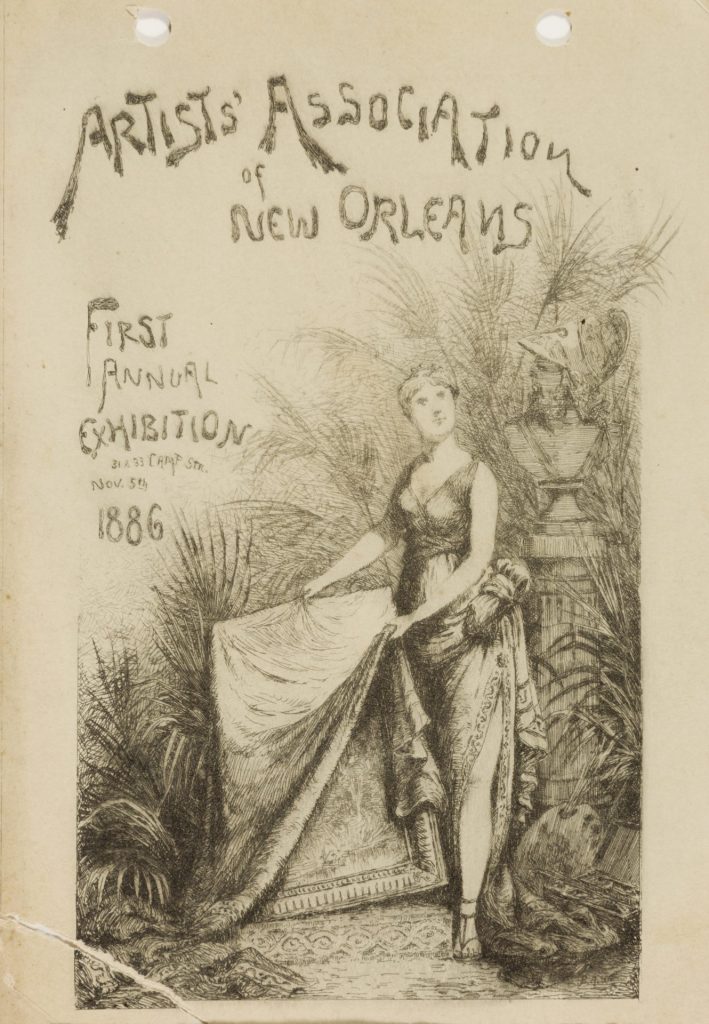

Bror Anders Wikstrom, Announcement for the First Annual Artists’ Association of New Orleans Exhibition, 1886. Lithograph. New Orleans Museum of Art, Anonymous Gift, 89.11

Wikstrom’s talent found him success as a marine and landscape painter, portraitist, cartoonist, and organizer of the turn-of-the-century New Orleans art community. Wikstrom was one of the founders of the New Orleans Artists Association in 1885, one of the civic groups that sparked the organization of the Delgado Museum of Art (today’s NOMA) in 1910.

Bror Anders Wikstrom, Western Landscape, c. 1900. Watercolor on paper. New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Prescott N. Dunbar, 86.72

Wikstrom had arrived in New Orleans a well-travelled man, and continued his explorations even after he’d settled in this city for 25 years. He took annual trips to Europe, and travelled Mexico widely recording what he saw through his brush, like on the c. 1900 Western Landscape watercolor in NOMA’s collection. These trips provided material for Wikstrom’s large oil on canvas landscape and marine scenes. A few years after his untimely death in 1909, these paintings were celebrated in the artist’s 1912 memorial exhibition at the Isaac Delgado Museum of Art.

Bror Anders Wikstrom, Morning on the Fishing Banks, 1899. Oil on canvas. New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Eugenia Uhlhorn Harrod in memory of her husband, Major Benjamin Morgan Harrod, 13.50

NOMA’s permanent collection includes the only known example of Wikstrom’s furniture design, a superb mahogany cabinet carved with a twin-tailed mermaid, dolphin, iris, and calla lily flowers. The whole design is in the fashionable turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau style, but also evokes Scandinavian wood carving traditions of Wikstrom’s birth country. This cabinet was gifted to the museum in 1914 by Mr. and Mrs. Gustave R. Westfeldt (who was president of the museum 1913–1915), a family of Swedish descent that supported the artist.

Bror Anders Wikstrom (American, born Sweden, 1854-1909), Cabinet, c. 1900-1905, New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. G. R. Westfeldt, 14.98

Bror Anders Wikstrom was so well-known by his New Orleans contemporaries that his name was carved into the stone on the architectural frieze on the 1910 Degado Museum (NOMA) building, alongside names of luminary artists like John James Audubon, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and John Singleton Copley. Wikstrom’s name can be found above the courtyard outside the Museum Shop.

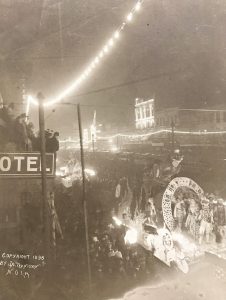

John N. Teunisson, photographer (American, 1869–1959), Street view showing Float #11 “The Devil’s Basket,” Krewe of Proteus, 1898. Photographic print. Carnival Collection, Tulane University Special Collections.

Wikstrom is best remembered, however, as a designer for elaborate Mardi Gras productions. Through the 1880s and 1890s, his fantastical designs elevated the extravaganza of Carnival in imagination and boldness. Each Mardi Gras parade would traditionally feature twenty main floats, along with bands, marchers, and horseback riders. The twenty floats were each accompanied by coordinating designs for more than 100 costumed riders, along with their outfits, jewelry, and accessories outlined on precise design drawings.

John N. Teunisson’s rare photograph shows a night time Mardi Gras parade, thought to be the first recorded. The 1898 image records how early night parades were illuminated by a combination of then-new electric light strings and the traditional flame “flambeaux” torches. The gambling scene float in the photograph is “The Devil’s Basket” design by Wikstrom for Proteus, so one can compare the design as it appeared to night revelers in New Orleans against how the float and costumes were imagined by Wikstrom in watercolor.

Bror Anders Wikstrom, Design for “The Devil’s Basket” float, Krewe of Proteus, 1898. Carnival Collection, Tulane University Special Collections.

Wikstrom’s design drawings mix of an evocative flourish that gives you the spirit of the design, but also are layered with pragmatic details like measurements, costume parts inventory, or the aerial plan you’ll sometimes find in pencil along the margins. The aerial plan for the “The Devil’s Basket” can be seen in the lower right corner of the drawing, and the numbers around the float align to the inventory number of the costumes.

Installation of Wikstrom designs for “The Alphabet” Proteus 1904 parade. Drawings on loan from Carnival Collection, Tulane University Special Collections in New Orleans Museum of Art Bror Anders Wikstrom: Bringing Fantasy to Carnival, Dec 22, 2017 to April 29, 2018.

NOMA’s 2017 exhibition Bror Anders Wikstrom: Bringing Fantasy to Carnival was anchored by the display of a full set of float designs for the 1904 Proteus “The Alphabet” parade, on loan from the Carnival Collection at Tulane University. Wikstrom’s vision for “The Alphabet” featured float themes derived from each letter of the alphabet–from the fierce battle atop the “D for Dragon” float to the glorious rainbow arching the “U for Unicorn” design. Notes on the edges of the margins tell us that the letters H and Q were represented by horseback riders acting as Heralds and Don Quixote.

In the celebrated turn-of-the-century drawings by New Orleans artist Bror Anders Wikstrom, we see the roots of the fantasy enacted during Carnival season today, when the New Orleans community, whether with a formal krewe or not, turns to their supply of wigs and costumes to adopt a dramatic alter ego.

–Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts & Design

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.