Walter Dorwin Teague, designer (American, 1883–1960), Steuben Division, Corning Glass Works (Corning, New York, founded 1903 as Steuben, acquired by Corning in 1918), “Lens” Bowl, c. 1932, Mold-blown Pyrex glass, 2 1/4 x 12 inch diameter, Gift of John Bullard in honor of Isidore and Marianne Cohn, 2014.11

This unadorned glass bowl displayed in NOMA’s decorative arts galleries is celebrated as art. No ornament or color is needed to decorate its form, as the concentric circles molded into perfectly clear glass make an elegant design statement. However, if one saw this exact same object affixed to the lead car of a quickly-approaching train, it might not be fully appreciated as a prime example of geometric reduction in 20th-century Modern art. This striking “Lens” Bowl was made in 1932 directly from the factory mold of a Corning Glass Company locomotive-headlight lens.

The optical science behind the headlight design dates back to the nineteenth century. French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel (1788–1827) innovated a glass lens made of concentric rings that captured divergent rays from a light source and directed them into a strong, single beam that could be seen from a greater distance. In their original application in lighthouses, “Fresnel” lenses saved countless lives from shipwrecks along perilous shorelines, and later were later adapted for use on locomotive engines, car headlights, and air-traffic signals still in production today.

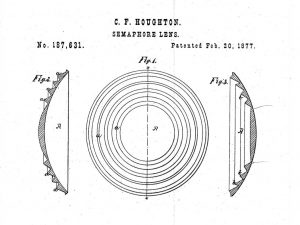

At New York’s Corning Glass Factory in 1877, Charles F. Houghton ( 1848–1897) patented the version of the Fresnel lens that later became a 1930s-era luxury bowl. Houghton, son of the Corning founder, filed the company’s improvement to the concentric circle type lens as a patent, writing:

“My invention relates to lenses which are employed in giving signals or used upon locomotive head-lights, or other lanterns when light is to be projected to a great distance; and it has for its object the production of a more durable cheap lens, adapted to the illumination of a greater surface, and giving a broader field of illumination than is possible in lenses as now constructed.”

Illustration from U.S. Patent US187631A, Charles F. Houghton, for Improvement In Semaphore-Lenses, patented Feb 20, 1877

Corning’s advancement in the production of glass lenses put the company at the head of an expanding market, and in a position to advise on railroad safety standards following a string of calamitous turn-of-the-century train accidents due to signaling errors. Working with experts on color theory, Corning chemist William Churchill identified the shades of red, green, and yellow that the human eye finds most distinctive in various weather conditions and the glass properties that make these precise colors. In 1908 the American railroad industry adopted Corning’s specified red, green, and yellow for use in traffic signals, resulting in an astonishing improvement in railroad safety. Fifteen years after the adoption of the standards, fatalities on American railroads dropped nearly seventy percent.

In the same town during the same years, and employing the same materials, another company formed with a different aim in mind. Steuben Glass Works formed in Corning, New York (Steuben County), in 1903 making art nouveau-style decorative objects in colored and metallic glass. When the company struggled during World War I in getting supplies, it was acquired by the more industrial-purposed Corning Glass Company, becoming a “Steuben Division” dedicated to artistic glass production. Steuben was known for a refined lead crystal-clear glass that refracted light beautifully.

During the Great Depression, and the resulting decline in profitability for luxury goods, the Corning team hired Walter Dorwin Teague, one of America’s first “industrial designers,” to bring a modern aesthetic to Steuben art glass. Teague’s eponymous New York City design firm, established in 1926, put their design and marketing vision on icons ranging from UPS trucks and Texaco gas stations to Kodak cameras and Boeing airplanes. During Teague’s 1932 contract year with Steuben, he stripped away fussy decoration and color in favor of the style of Modern glass coming out of Scandinavia and geometric simplicity that allowed the material of crystal glass to take focus.

Teague’s purposeful simplicity in design, however, was not an indication of any egalitarian motivation. Teague wrote to Corning’s Amory Houghton in October 1932, recommending they position Steuben as a symbol of aspiration: “We must work to establish Steuben as the finest glassware in America, worth all we ask for it. I believe we can make the ownership of Steuben glass one of those evidences of solvency—like the ownership of a Cadillac Sixteen or a house in the right neighborhood.”

The 1932 “Lens” Bowl stands out as a remarkable design within Teague’s work with Steuben. Teague’s fascination with the geometric pattern on an industrial lens mold at the factory led to this bowl, which differs only from identical locomotive train glass lenses in having its base polished to a luxurious shine. Though it did not have wide success in the 1930s luxury market, meaning few of this rare bowl were made, the “Lens” Bowl became an iconic application of Modern design theories into a manufactured domestic object. Teague’s design does away with ornamentation to instead focus on elemental geometry, it celebrates human advancements in material science, and, if you think deeply enough about the history of the design, it honors the scientific ingenuity that saved lives through advancements in light-signaling technology.

Rather than a mere gimmick, the “Lens” Bowl is part of the important Modern design movement that openly paid tribute to new materials and thoughtful industrial production. Like honoring the genius of a useful paperclip, the practicality of a laboratory’s glass beaker, here Teague’s design embodies the beauty of the machines that made Corning’s industrial advances possible.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.