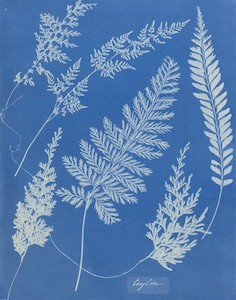

Anna Atkins (British, 1799–1871), Ceylon [examples of ferns], between 1852 and 1854, Cyanotype, Museum purchase, General Acquisitions Fund, 81.385

The London Botanical Society made Atkins an official member in 1839. Soon after, Atkins began studying with William Henry Fox Talbot (the inventor of the negative-positive process) and Sir John Herschel. Herschel created the cyanotype process, which results in the beautiful cerulean color of this cyanotype. Atkins made her photographs by placing plants directly on chemically treated paper and exposing the combination to sunlight, creating a negative image of this fern.

Atkins made all of her cyanotypes in England, often receiving specimens through imperial trade. This image, therefore, was produced over 5,000 miles away from where the plant originated, and now resides in New Orleans—nearly as many miles away from where Atkins lived! Which is to say, Atkins’ photograph is emblematic of photography’s importance for our ability to study ecology and share that knowledge with others.

Here we have a precisely detailed and objective image of a plant that can be transported and shared around the world. At the same time, the technology available to Atkins also had limitations as a tool of scientific observation, namely preventing us from knowing the plant’s color or providing a real sense of the specimen in three dimensions. I would offer that the exclusion of those details help make Atkins’ Ceylon such a straightforward, quietly stunning photograph about the diversity and beauty of our natural world.

—Brian Piper, Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator for Photography

▶ For a related hands-on art project, learn to how make a solar print at home.

NOMA members inspire the love of art in every visitor who walks into the Great Hall or through the gates of the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden.

In addition to enjoying benefits like special members’ previews of exhibitions, free wellness classes surrounded by sculptures, and a complimentary subscription to NOMA Magazine, our members enable schoolchildren to discover the Old Masters, community members to engage with world-class art and local artists, and NOMA’s curators to present innovative and provocative exhibitions year after year.

▶ JOIN TODAY