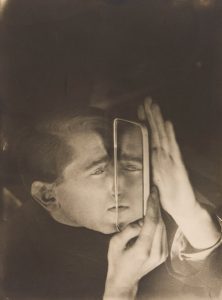

Lotte Stam-Beese (German, 1903–1988), Albert Braun with Mirror, 1928, Gelatin silver print, 4 11/16 x 3 7/16 in., Museum purchase, General Acquisition Fund, 82.102

The Bauhaus School of Design was established on an almost utopian ideal: that thoughtful art, design, and craft could and should be a part of every aspect of daily life. The profundity of this ideal, executed to the fullest extent, would result in people living in houses of Bauhaus design, eating with flatware off of ceramic dishes designed at the Bauhaus, all the while surrounded by works and decoration inspired by the design and teachings of the Bauhaus. Lotte (Charlotte) Beese arrived at the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, not as a photographer—it only became a formal part of the program in 1928—but as a textile design and architecture student. Nevertheless, it is a testament both to the successful saturation of the Bauhaus principles and to Beese’s own synthesis of them that she could produce a photograph as evocative of those principals as this one, which is an excellent and artful piece of design, a metaphor for photographic vision, a beautifully crafted print, and a playful portrait of one of her fellow students in the textile program, Albert Braun. The carefully placed mirror allows one half of Braun’s face to replicate itself, creating an unsettling double that throws the act of looking into the abyss, as if Braun’s own vision permanently returns itself. The slight angle of the mirror, however, also mischievously redirects his gaze to confront the camera lens, Beese, and, by extension, us, the viewer. This subtle detail forces us to engage with the reflection instead of the reflected, with the surface instead of the substance, creating a corollary for looking at a photograph within the photograph itself.

The mirror also serves as an extension of Braun’s vision, telescoping it out through multiple surfaces and across time and space. This too is in keeping with the conception of the camera and photography at the Bauhaus. In 1925, when László Moholy-Nagy published his influential Painting, Photography, Film (a Bauhaus publication), he argued for photography’s role as a creative technology, a productive and reproductive phenomenon capable of extending human vision. As he put it, the camera could “make visible existences which cannot be perceived or taken in by our optical instrument, the eye.”[1] Here, the image emphasizes photography’s role in “making visible” ourselves and others, since it includes both a self (Braun) and its other (the reflection).

As Moholy-Nagy’s ideas fomented change at the Bauhaus, they also seeped into the consciousness of the student body and provoked the adventurous, like Beese, to use the camera creatively in even the most casual sessions. This is one of several portraits of Braun made around the same time that show both the sitter and the photographer being typical college students: experimenting only half-seriously with a variety of contrived poses. Here, Braun and Beese managed to produce a photograph that is very much about photography—or at least the Bauhaus conception of photography—invoking contemporary attitudes about photographic production and reproduction in an image that invites us to look, and then look again.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.