NOMA+, a mobile pop-up museum that debuted in 2018, continues to serve audiences and communities who have historically not been engaged with the New Orleans Museum of Art. For two days in June, Community Engagement Curator Nic Aziz led an art worskhop with students at the Travis Hill School within Orleans Parish Prison, one of only three full-day high schools in the US that operate for inmates within an adult penitentiary. In this blog post, Aziz shares his impressions of working with these students on a project related to a recent exhibition of Haitian Vodou flags, Bondye: Between and Beyond.

On the evening of August 14, 1791, hundreds of enslaved Africans from across the island that is now known as Haiti and the Dominican Republic (then known as Saint-Domingue) gathered in secret in the middle of a forest for a Vodou ceremony that became the official beginning of the Haitian Revolution. The ceremony was led by a Jamaican houngan (Vodou priest) named Boukman Dutty and a mambo (Vodou priestess) named Cecile Fatiman. After more than a decade of fighting the French and Spanish for their independence, these enslaved Africans officially declared their freedom and established Ayiti (Haiti) as the first independent black republic in the world in 1804.

This literal and spiritual fight for freedom would go on to inspire freedom movements across the Americas—and its influence can be seen in countries such as Brazil, Venezuela, Columbia, and Cuba. This influence was especially apparent in the United States as Haiti’s victory affected the doubling of the country’s land mass through the Louisiana Purchase and six years after this brought just under 10,000 Haitians to New Orleans, doubling the city’s population and bringing many of the city’s most prominent cultural fabrics (i.e. shotgun houses and second lining).

Despite this heavy influence, Haiti’s impact on New Orleans culture is just beginning to gain recognition on a broader scale with occurrences such as current Mayor LaToya Cantrell recently referring to the city as “Haiti’s first diaspora.” Ironically, New Orleans’ relationship to Haiti has even deeper metaphorical connections as so many individuals (mostly young African-American men) continue to fight for the freedom that was gained by Saint-Domingue’s enslaved Africans now 215 years ago.

When former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu took office in 2010, New Orleans’ jail population was 3,300. As a result of this and the heightened media attention on the city following Hurricane Katrina, the issue of mass incarceration began to come to the forefront of local, national and global conversations concerning the city. By 2012, New Orleans was known as “the world’s prison capital” as it had the highest incarceration rate in the United States and was nearly five times that of Iran, thirteen times that of China, and twenty times that of Germany.

In 2011, New Orleans was one of five cities to win a national grant competition through what was known as the Mayors Project, a government innovation program through Bloomberg Philanthropies. A total of $24 million was disbursed through these five cities to help each create teams and fund programs that would address the most pressing challenges within them. New Orleans was given $4.2 million and used this funding to create what would be known as the city’s Innovation Delivery Team – and their initial foci would be to develop strategies to reduce murder and improve governmental customer service. One of these results would become known as the NOLA FOR LIFE strategy which was launched in 2012 and served as arguably the Landrieu administration’s most prominent implementation through the end of his administration in 2018. The strategy consisted of more than 20 different programs that all focused on the reduction of murder in New Orleans and featured a combination of New Orleans-specific programming along with evidence-based initiatives such as renowned criminologist David Kennedy’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy. I had the privilege of serving as a project manager on this team from January 2014 through July 2016 and in this role got to gain some very important perspective on the power of collaboration.

By the time I joined the team, the NOLA FOR LIFE strategy had begun to prove its efficacy as by the end of the 2014 it was announced that New Orleans had 150 criminal homicides that year, marking its lowest total since 1971. With this success, the team and administration were able to think about expansion which would lead to the creation of an official economic opportunity strategy. The majority of my first year was spent assisting the creation of this strategy and I would spend the rest of my tenure on the team managing initiatives within these two strategies. Because both were so dependent on community partnerships, I believe that I gained invaluable experiences and learned the true importance of community collaboration – a knowledge and skillset that I now use extensively in my role as Community Engagement Curator at the New Orleans Museum of Art.

One of the key components of the Innovation Delivery Team model was annual instances when we would come together as a team, evaluate our progress and propose new initiatives. As someone who was very passionate about culture (and a budding artist and curator who didn’t know it yet), the majority of my suggestions for new offerings related to art in some manner.

Some of these included the addition of art therapy and meditation programs to our murder reduction portfolio of work. Unfortunately these suggestions never gained any real traction—I believe partly due to a lack of collective support and partly because they were much more qualitative, abstract and long term in their approaches. Despite never becoming actualized programs, I would be able to utilize this type of thinking in a very full circle manner five years later through NOMA+’s most recent partnership with the Travis Hill School.

Travis Hill School was created in 2017 as the result of the Orleans Parish School Board signing a contract with national non-profit Center for Educational Excellence in Alternative Settings to operate the school. Named after the renowned local trumpeter affectionately known as “Trumpet Black” who passed away suddenly in 2015, the school committed to serving incarcerated youth along with any 18 to 21 year olds who were close to getting a high school diploma. Despite being incarcerated and awaiting trial, these students take the same standardized tests as all students in Louisiana and rotate among all major course offerings including art.

My connection to the school was the result of one of their staff members, Elishia McAllister, who I met almost a year prior during a community event at the Ellis Marsalis Center where I was with our NOMA+ mobile museum unit. From that point we stayed connected and she eventually reached out, expressed an interest in me working with their students and introduced me to the school’s art teacher, Patricia Laing. Patricia and I then coordinated over several months to solidify what would become the two-day workshop that took place at the school in June. During our correspondence period, we mostly talked about the logistical aspects of the workshop—what I could and couldn’t bring, the number of students in each class, etc.).

The moment I arrived at the Orleans Parish Prison, I knew it would be an extremely emotional and visceral experience as this was my first time in an adult prison (the other time was at our youth prison, dubbed the “Youth Study Center,” located in the Saint Bernard area of New Orleans). As I parked and walked into the building, I made sure to mentally prepare myself for what I was about to experience, while also preparing for the sessions that I would be leading through the day. After signing in with the security guard on the first floor, I waited for the Travis Hill staff member (Ms. Nealy) to come down and bring me up to the school on the second floor. Once on the second floor, the reality of the experience truly set in as I began my first of several engagements with security. I was given a briefing on what was considered “contraband” and as a result had to leave my laptop in a locker next to the security desk. I then had to have my box of art materials checked, go through a body scanner and be scanned again by the guard with a handheld security wand. Following these scans, I then had to be given access through two different levels of large electric hollow metal doors to officially enter the prison. It should also be noted that this is an emotionally jarring process that all Travis Hill staff members must go through each time they step outside of the facility (i.e. to eat lunch, to get some air, to check their phones that they’re not allowed to bring inside, etc.).

As I walked down this first main hallway, I briefly talked with Ms. Nealy about my background and her current experience as a parent who was struggling with having an athletically gifted son choose a different path in college than football. Midway through this conversation, my reality was slowed down and interrupted by the site of a man limply walking across the hall in an orange jumpsuit with his hands and ankles chained. He of course resembled me and the more than 80% of incarcerated individuals in New Orleans’ prison population who are also African American men—and I’ll never forget this image and the feelings I felt as it occurred. While this was an image I had seen before through my work in the Mayor’s office and being in courtrooms with many of these individuals at once, seeing it this close in an actual prison was a completely different experience. After this brief reality intermission, I returned to my presence within the conversation with Ms. Nealy and got on the elevator to the third floor where the art class was located. By the time I arrived in the classroom, this first period was near its end and after briefly meeting Ms. Laing (the art teacher) for the first time in person, she introduced me to the students who were about to leave and told them that I would be back to work with them on Thursday. I used these few moments to further prepare myself for the next group of students who were on their way.

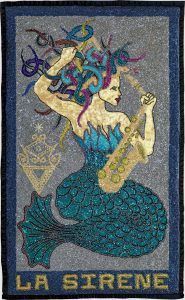

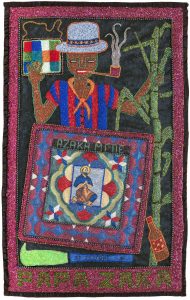

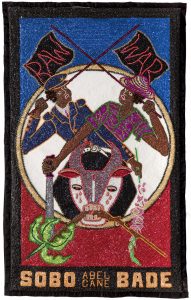

With each workshop or pop-up experience that I have facilitated thus far through our NOMA+ community engagement strategy, there has been a relationship to an exhibition that is on view in the museum. With this workshop at Travis Hill, I was able to incorporate an exhibition that I had the opportunity to co-curate which was on view at NOMA from January 25th – May 27th, 2019. The exhibition was entitled Bondye: Between and Beyond and featured 14 sequined Vodou prayer flags made in the early 1990s by Louisiana-born artist Tina Girouard along with renowned Haitian sequined artists such as Edgar Jean-Louis and Georges Valris. Each flag represented a different “lwa” (spirit) within the Vodou religion and they play an important role in Haitian culture, gatherings and rituals. These lwa stand at cultural and spiritual crossroads and serve as intermediaries between humans and “Bondye,” the supreme being who represents unity and the highest principle of the universe. Additionally, as mentioned in the curatorial text, “these works prompt us to consider the ways we all exist between different cultures, contexts and experiences and explore our many points of connection with the rest of the human family.” As I stood in front of this class of young African-American men who all sat in orange jumpsuits, I realized that the moment and workshop was a beautifully kismet manifestation of this prompt.

We all existed together in that room at this unique point of congruence, finding points of connections despite the differences in our current lived experiences. I was there with the opportunity to utilize history and art as a bridge and catalyst to create space for connection and exploration, with these students who were existing in an environment that too often diminishes their value within the aforementioned human family. We were able to instantly establish connections – whether it was our shared New Orleans nativity or their admiration of the shoes I was wearing or the similar musical artists that we listen to.

Like most of the workshops that I lead, I began by assessing their familiarity with NOMA and the term “curator.” As expected [and as is the case with the majority of workshops I conduct], there was very minimal familiarity with NOMA and absolutely no familiarity with the term curator. After a brief explanation of the role of a curator, I used this to transition into an explanation about the historicallyexclusionarynatureofmuseumsandmyspecificroleatNOMA.“Whatpercentageof museum visitors across the country do you think look like me and you,” I asked. In each group I took several guesses and there was only once or twice throughout the entire day that any of them were even close to the actual percentage. Each time when I would reveal that a 2010 study found that only six percent of museum visitors across the country were African American, there would be surprise and I used this to create a discussion about why they thought that this number was so low. Many of them identified reasons such as just a general “lack of interest in art” among certain cultures, while some occasionally insinuated a lack of interest due to a lack of artwork that resonated with these cultures. From this point, I led into an exercise and discussion that forced them to reflect on their familiarity with the city that we call home.

“What do y’all know about Haiti?”

I’d get quick answers to this question, show the country’s flag, and lead into an activity l call “New Orleans or Haiti” – a simple exercise that I created as an engagement tool for the Bondye: Between and Beyond exhibition. It is one in which I show different pictures of New Orleans and Haiti and prompt participants to denote which was which. As expected, the students had trouble choosing which were New Orleans and which were Haiti – but interestingly enough some of the groups did exponentially better than the myriad of groups throughout New Orleans that I’ve done this exercise with to date. After clarifying which was which and watching the beautiful banter filled with “I told you that was New Orleans!,” I would ask if they had an idea of why the exercise was so confusing. After taking answers ranging from “similar cultures” to “they’re both poor and black,” I led into a brief history lesson.

Using the technologically opulent SMART board, I pulled up google image results for “Le Bois Caiman” and explained the beginning of the Haitian Revolution. From there I referenced the country gaining its independence to become the first black republic in the world and the impact that that had on New Orleans and the rest of the United States. “Five years after Haiti gained their independence, nearly 10,000 Haitians came to New Orleans and they brought shotgun houses, second lining and creole cottages,” I’d say. “This is why that game was so difficult.” After providing this context, I’d bring it back to Bois Caiman to relate all of this to the Bondye: Between and Beyond exhibition and the four elaborate foam core reproductions of the featured flags that I had with me.

What do y’all know about Vodou?

This question would get many more responses than the Haiti one and included some such as: “That’s that magic and spell stuff” or “evil dolls” or “that famous lady that’s buried in that cemetery” (Marie Laveau). From there, I’d go back to the images of Bois Caiman and explain how the Haitian Revolution began with a Vodou ceremony – and then explain the irony that we’ve been conditioned to view Vodou (and other African spirituality practices) as “dark” and “bad” despite the fact that it literally was the catalyst to our liberation. I’d then give a brief explanation of Vodou, the purpose of sequined prayer flags and the meanings behind each Lwa represented in them. The flags that I had with me included Erzulie, Simbi, Grand Bois and Ogou. While each sparked interest in different ways, I always ended by presenting Ogou – the Lwa that is associated with freedom, power and strength. It is also believed that Ogou is the Lwa who possessed the enslaved Africans during the Haitian Revolution and propelled them to gain their independence. Unsurprisingly, this lwa and the flag resonated with many of the students as a result of its association to freedom. The monumentality of explaining the meaning behind a sequin beaded flag of a Vodou spirit that is believed to have possessed enslaved Africans to victory to become the first independent Black republic in the world, to students who were sitting in front of me in orange jumpsuits with their ankles chained together, will forever be etched in my consciousness.

After explaining each flag’s purpose and meanings, I explained that everyone would have the opportunity to make their own flags. “Just like each of these flags represent something different, what would your flag represent,” I’d ask. From here, I’d give each student a canvas banner flag and prompt them to take some moments to think about how they’d like to design their piece. In addition to the flags, I brought a myriad of different sequins and other types of beads and gems that students could glue onto their flags. While some jumped right into creating their flag, others needed a little more guiding. I tended to use questions like “what are you most passionate about” or “what about yourself do you hope to portray to other people.” While each student and their unique creations stuck out in my mind, there were a few whose interest and skill made them especially memorable.

In one group, there was a student named Erick who was from the Seventh Ward and very fond of rap music. As he intently glued beads to this flag, we got into a discussion during which he recommended several up and coming New Orleans rappers that I should listen to. The concept of freedom from Ogou’s flag was particularly striking for him and he derived much influence from it for his piece.

Tina Girouard, OGOU, 1992, Sequins, beads, fabric, 43 x 72 in., Collection of the Artist ©Tina Girouard Photography by Roman Alokhin, courtesy New Orleans Museum of Art

In another group, there was Edwin, also known as “Spaz.” He was from Baton Rouge and arguably the most attentive student from any of the groups. His eyes never wavered and he asked extremely insightful questions that showed a heightened level of interest. Before he left the room, he came up to me, shook my hand and said “I really like art and what it can do to your mind…I like where your head’s at.” Before he left I briefly used the SMART board to show him images of African-American artists who often make work about his experience like Hank Willis Thomas and Dread Scott—and I told him that I’d show him more artists like these during the next session.

Last but not least there was Jameal, who I didn’t get to meet properly until the second workshop day. I learned from a staff member during the afternoon of that first day, and from Jameil on the second day, that his great-grandmother was Haitian. He had apparently created another art piece earlier in the year that incorporated his Haitian heritage. As a result, his interest and above-average knowledge about Haiti showed emphatically during the second day and he worked intently to lay the foundation to another Haitian-themed piece of art.

This two-day experience at Travis Hill School was undoubtedly one of the most moving experiences of my life. Having the opportunity to use art in that environment felt like such a full circle moment from my first professional role working for the Mayor’s office after returning to New Orleans. In addition to the insight I gained from my interactions with the students, my eyes were also opened to the extremely emotionally taxing nature of that environment for all involved. The stiff gut-wrenching feeling of the entire building is extremely protruding and these anxieties are compounded if you are an African-American man constantly having to look into this sinister mirror. Whether having to listen to the random instances of screaming during altercations, or forcing students to wait in the hall after class is over to confirm that there is the same number of pencils left in the room or looking down and re-realizing that their ankles are shackled together – the reality of the environment has a way of throwing frequent and weighted reminders of its harshness. While our world currently has so many different types of freedoms that are being fought for, these students are unfortunately in the middle of the most similar manifestation of what the enslaved Africans sought when they met in the middle of Haiti’s woods in August 1791. Perhaps just like Bois Caiman, or even the Civil Rights Movement, the root of their liberation might rest in tapping into their spirituality – and what better medium than art to help ignite their journey to this source?