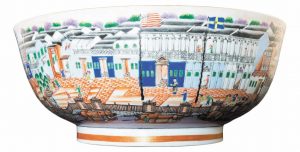

Chinese, for Western market, Punch Bowl with Cantonese “Hongs,” 1788–1790, Porcelain, enamel, 5 7/8 x 14 3/8 in diameter, Museum purchase, Elise Mayer Besthoff Fund, 2018.27

A newly acquired Punch Bowl with Cantonese “Hongs,”on display in the Lupin Gallery of Decorative Arts, reveals both the exquisite craftsmanship of Chinese porcelain and a window into international trade of the late eighteenth century.

Enameled around the outside of the bowl is a continuous scene of a bustling waterfront along China’s Pearl River. Small river craft are being loaded with cargo as men in Eastern and Western dress scurry along the docks. Impressive buildings line the water’s edge, each distinguished with a national flag. The bustle of commercial activity shown is a rare depiction of the Chinese trading port of Canton (today’s city of Guangzhou), circa 1790, meticulously painted and fired onto porcelain.

Export Chinese porcelain was highly in-demand among Europeans as early as the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), with trade occurring at first over land along the Silk Road, and then by sea beginning in the early sixteenth century. By the eighteenth century, both Europe and the Americas had intense desire for China’s white porcelain, along with Chinese tea, spices, and textiles. Imperial China, however, was officially considered a self-sufficient economy that was closed to foreign access. Between 1757 and 1842 “The Canton System” allowed for only limited and highly regulated international trade from China’s major southern port at Canton. Foreign traders were confined to wharves along the Pearl River.

Punch bowl with Cantonese “Hongs” details this area of riverfront “hongs,” or the combination warehouse, office, and living spaces for the international ship captains and tradesmen visiting China. The bowl shows the flags of Denmark, the Spanish Philippines, France, Sweden, Britain, The Netherlands, and the young United States. The presence of the US flag helps to date this bowl, as we know that America entered into direct trade with China in 1784 after the American Revolution.

These bowls were likely made in China specifically as a souvenir of sorts for a Western captain of the commercial China trade. For one thing, punch drinking was not customary in China, so all large porcelain punch bowl forms were made specifically for the export to the West. A hong scene painted on porcelain is relatively rare—fewer than 100 are known—but the Canton waterfront became a revered scene in paintings and prints by both Chinese and American artists.

NOMA’s hong bowl is displayed next to yet another treasure of related interest—a gilt and enameled Automaton Clock manufactured in London, circa 1800. This musical timekeeping showpiece was likely made in England specifically for the Chinese market, as clocks were one of the few potential imported Western goods that were valued by the Chinese. China’s Emperor Qianlong, who reigned from 1711 to 1799, wrote in 1793 to England’s King George III: “Our Celestial Kingdom possess all things in abundance and wants for nothing within its frontiers. Hence there is no need to bring in the wares of barbarians.” Decidedly non-barbaric exception were mechanical clocks and gadgets from London, which the Emperor and the Chinese elite valued as much as the Western elite valued their fine Chinese porcelain and tea. These two objects together reflect the long and complicated international trade relationships between the East and West.

Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design