Enrique Alférez (Mexican-American 1901-1999), Symbols of Communication, 1967, Plaster, rebar, paint, Dimensions variable, 118 panels, Gift of Joseph Jaeger, Barry Kern, Michael White, and Arnold Kirschman, 2020.7.1-.118

At the New Orleans Museum of Art, the writing is literally on the wall—or a display case. Words are not only visible in descriptive labels but also in select paintings and decorative arts that feature written communication. Perhaps the most dramatic expression of this meeting of arts and letters is the recent installation of a room-sized mural by New Orleans’s own Enrique Alférez (1901–1999). Commissioned for the escalator atrium of the Times-Picayune building in 1967, Symbols of Communication was donated to NOMA after the newspaper relocated its headquarters and the property was razed in 2019. The large-scale bas relief now covers three walls, from floor to ceiling, in NOMA’s new multipurpose Lapis Center for the Arts that will officially open in late April.

Symbols of Communication includes characters from alphabets that span time and geography. Mayan glyphs and Egyptian hieroglyphics are juxtaposed against the swirling logograms of Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese script, the connected lines of phonologic Greek and Roman letters, and the dots and dashes of Morse code and Braille. These varied examples of print language are present in many works, including the following four examples that feature poetry, royal titles, a sermon, and even historic legal documents.

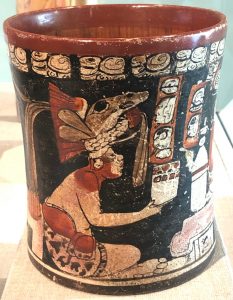

Maya Culture, El Peten, Guatemala, Cylindrical Vessel Depicting Enthroned Lords and Attendants, c. 600–900, Terra cotta with polychrome, 6 5/8 x 5 1/4 in., Ella West Freeman Foundation Matching Fund, 69.33

Maya script, also known as Maya glyphs, is the only ancient Mesoamerican language to be substantially deciphered. The earliest inscriptions discovered by archaeologists date to the third century BCE and the writing was in continuous use until the Spanish conquest of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. A polychrome vase in NOMA’s collection from the Northern Peten in Guatemala depicts two enthroned rulers, their attendants, and numerous glyphs. Broad headdresses and heavy necklaces distinguish these lords from subservient figures featured on a lower level of the vessel. Research has led to the supposition that the attendants are women. The names and titles of all four figures seem to be inscribed in vertical columns of glyphs. An animal head with a protruding tongue, identified as Manik (glyph 671), occurs in the names of all four personages on the vase.

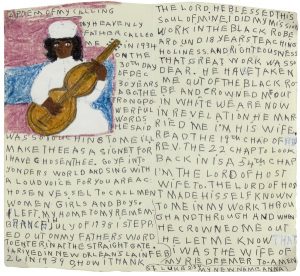

Sister Gertrude Morgan (American, 1900–1980), A Poem of My Calling, c. 1970, Crayon, tempera, graphite, and ballpoint ink on paper, (8 1/4 x 9 in., Gift of Maria and Lee Friedlander, 2000.108

Sister Gertrude Morgan’s artistic career is inextricably linked to her spiritual calling as a prophetess and missionary. Born in 1900 in Lafayette, Alabama, Morgan began preaching in her mid-thirties. By 1939 she moved to New Orleans, where she became a fixture in the French Quarter as a sidewalk evangelist and gospel musician. Morgan’s stream-of-consciousness sermons took on a physical form when she began painting in 1956 by divine command. She always gave credit for her artwork to the Lord, who she believed guided and nourished her talent. Morgan used any object close at hand when the “spirit” moved her to create art, including cardboard, window shades, styrofoam trays, plastic utensils, jelly glasses, blocks of wood, lamp shades, picture frames, her guitar case, and even the back of a For Sale sign placed in her yard by a real estate agent. In Poem of My Calling Morgan uses crayon, tempera, graphite, and ballpoint ink on paper to recount her spiritual awakening, which includes a self portrait with guitar in the upper left corner. The autobiographical prose begins:

MY HEAVENLY FATHER CALLED ME IN 1934 ON THE 30th DAY OF DEC. 30 YEARS AGO. THE STRONG PO- WERFUL WORDS HE SAID WAS SO TOUCHING TO ME I’LL MAKE THEE AS A SIGNET FOR I HAVE CHOSEN THEE. GO YE INTO YONDERS WORLD AND SING WITH A LOUD VOICE FOR YOU ARE A CHOSEN VESSEL …

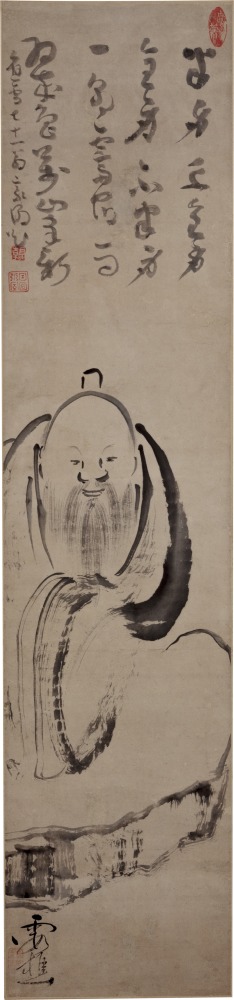

Ike Taiga (Japanese, 1723–1776), Sage by a Rock, Singature: Kasho, Seal: Kasho, Inscription by Gocho Kankai(1739–1835), dated 1809, Ink on paper, 46 1/8 x 10 1/2 in., Gift of Kurt A. Gitter, MD, and Millie H. Gitter in memory of Dr. Harold P. Stern, Director, Freer Gallery of Art, 1972–1977, 77.20

The Nanga (“southern painting”) or Bunjinga (“scholars painting”) school emerged in early eighteenth-century Japan, inspired by Chinese literati painting. The imported style gradually grew in popularity among a first generation of Japanese painters who borrowed elements from this Chinese tradition. The evolving genre ultimately passed to an exceptional young artist, Ike Taiga, who became the most influential Nanga master in Japan. After hearing Zen sermons by the great Rinzai master Hakuin, Taiga executed works in the style of Zenga, a combination of calligraphy and painting distinguished by rough, powerful brushwork. One such work is Sage by a Rock (1809) which includes a later inscription by the Buddhist monk Gocho Kankai (1739–1835), who wrote:

Half a body is not a whole body,

A whole body is not half a body,

In the morning the rain clears,

And the myriad peaks are newly green.

Marinus van Reymerswaele (Dutch, 1495–1566), The Lawyer’s Office, 1545, Oil on wood, 40 1/8 x 48 5/8 in., Ella West Freeman Foundation Matching Fund, 70.7

Paintings by European masters of Northern Renaissance realism often recorded official contracts or acts. Marinus van Reymerswaele’s painting The Lawyer’s Office (1545) is a remarkable example of this practice. Research has demonstrated that the handwritten documents in the background of the painting, executed with legible detail, refer to an actual lawsuit begun in 1526 in the Dutch town of Reymerswaele on the North Sea. The suit arose between three heirs of Anthonius Willem Bouwenz and Cornelius vander Maere, the latter having purchased a salt mine from the heirs of Anthonius. Conflict ensued when Cornelius refused to make the initial payment and subsequently had his goods seized. The legal transactions lasted until 1538, by which time the property under dispute had probably been submerged or destroyed by storms. Ironically, the court fees still had to be paid.

Portions of this feature were excerpted from descriptions in the New Orleans Museum of Art Handbook written by Lisa Rotondo-McCord, Joan G. Caldwell, Stephen Adiss, and Sharon E. Stearns. The Handbook is available for purchase in the Museum Shop.

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.