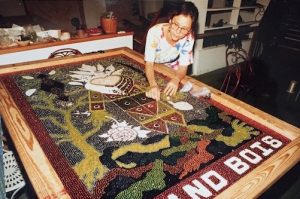

Tina Girouard, a Lousiana-born artist who became a key figure in the New York art scene of the 1960s and ’70s, died on April 21 at age 73. Born in 1946 in DeQuincy, Louisiana, Girouard frequently focused her art on Francophone cultures in her home state and beyond. In the 1990s she worked in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, among local artists and wrote a book on the use of sequins in Haitian art. She also crafted sequined works of her own that pay homage to Vodou flags honoring spirits known as lwa. “Something within us all is unknowable and unchangeable,” she once wrote, adding, “Life and death form a whole as we flow along our mystical voyage—a delicate, solo dance.” Girouard’s most recent exhibition at NOMA, Bondye: Between and Beyond, featured sequined prayer flags inspired by twelve lwa (spirits) of Vodou. Curator Nic Aziz shares his thoughts in this tribute to the artist.

Throughout much of the eighteenth century, rebellions swept across the Caribbean and South America. Enslaved Africans, often allied with free people of color, were constantly fighting for the abolition of slavery and freedom from colonial power. Ironically, these rebellions were often influenced by British and French seamen who shared news of insurrections in other locales, most notably the French Revolution. The common bonds between the oppressive experiences of these seamen and the enslaved Africans created unique bonds—to the point that many Africans during this period buried seamen who died on these islands in their cemeteries.

While the end of slavery was the primary goal of these rebellions, there was another arguably even more harmful transgression whose eradication was significant to the insurgents—race. As formerly enslaved Africans began to take control of Saint-Domingue (now known as Haiti) at the end of the eighteenth century, and word of this uprising began to spread throughout the Caribbean and the world, the rejection of societies being rooted in racialist ideologies spread to other nations. In his book A History of Jamaica, originally published in 1807, author Robert Renny references a song that was frequently sung in the streets of Kingston in 1799:

One, two, tree,

All de same;

Black, white, brown,

All de same:

All de same.

This song-based example of an egalitarian society free of racial hierarchy is one that would eventually be attempted, but unfortunately never fully realized due to many of the deeply damaging ramifications of race’s creation. Race is a construct that, since its inception, has impacted nearly every aspect of human existence. Its effects have led present-day scholars, such as Professor Barbara J. Fields, to extensively study the phenomenon and create new fields of study and terms such as “racecraft.” While many of us can acknowledge the illusory nature of race, due to its implications, particularly over the last four hundred years of human history, we must simultaneously acknowledge its complex impact on how we have and continue to exist.

When I was asked to co-curate Tina’s exhibition of Vodou prayer flags with Katie Pfohl toward the end of 2018, the concept of “race” was at the forefront of my thinking. I was somewhat familiar with her artistic practice, but I was much more familiar with the fact that she was an artist of European descent making Haitian flags. As a Haitian-American, and someone who has done extensive Haiti-centered work in New Orleans since 2015, my curiosity was naturally piqued. Curating this exhibition provided me with an opportunity to learn more about my culture and this specific aspect of Tina’s practice as an artist while also creating space for me and our museum visitors to explore complex issues related to race, culture, and appropriation.

From these initial inquiries, I believe that there were two particular curatorial decisions that improved the exhibition’s efficacy. The first was the exhibition’s name, which was altered to Bondye: Between and Beyond, in an effort to illuminate Haiti’s deeply underdiscussed influence on New Orleans and the world. “Bondye” is regarded as the supreme being within the Vodou religion, a religious practice whose roots exist in modern-day Benin and arrived in New Orleans largely with an influx of migrants following the end of the Saint-Domingue Revolution in 1804. Second was the development of a program at NOMA that would give our community the opportunity to engage in a discussion around the more controversial aspects of the exhibition, such as cultural appropriation. This became a panel discussion held in March 2019, entitled “Considering Cultural Exchange,” which was an extremely rich conversation around appropriation, exchange, and collaboration. Despite these and other curatorial aims, there were still criticisms of the exhibition. Some of these critiques were warranted, however I believe that their existence in our collective conversations affirmed the power of art. “Great art,” as I have come to learn, has the ability to spur questions and dialogue from the viewer—and in this case the story behind the work created just as many, if not more, of both.

Tina’s dedication to Haiti was unceasing from her first moments engaging with the country. After twenty years of researching Haiti’s connection to her native Louisiana, she traveled to the country for the first time in 1990. In her book, Sequin Artists of Haiti, she refers to an almost immediate love and desire to live and work there after only several days traveling through Port-au-Prince and Jacmel. Through her travels, she was able to learn about the beauty and technical aspects of the sequin art practice while also noticing the practice’s deficiencies due to a lack of both artist credit on works and the dearth of women sequin artists.

Just before leaving Haiti during this first trip, Tina visited the renowned Hotel Oloffson where master sequin artist Antoine Oleyant had a studio at the time which was known as “Atelier Simbi.” In her account of the meeting, Tina reveals that she “froze” upon entry as she was struck by one particular piece, “a spectacular rendering of a bull.” This bull was Bossou, the lwa (Vodou spirit) who releases earth’s bounty as the master of agriculture. Tina purchased the Bossou piece and used it to propose an exhibition of Antoine’s work for the 1991 Festival International in Lafayette where she served as the president of the board of directors. At the festival, Antoine apparently greatly admired a “good luck” hat that Tina wore and right before he left Lafayette for New York to continue showcasing his works, Tina put the hat on Antoine’s head and said “see you in Haiti.” This small gesture of respect and admiration would become Tina’s first official artistic exchange with Antoine and the larger Haitian community.

When Tina revisited Haiti later that year and returned to Antoine’s studio, he welcomed her by wearing the lucky hat, which he had since decorated with sequins. He had also created another one for himself and the two artists began collaborating to create work that blended Western images from Tina’s life experiences with Haitian imagery from Antoine’s. As Tina wrote in her book: “Never intending to appropriate a traditional Haitian art form, my desire was to come to a point of collaboration naturally. Open to sharing our separate ideas, techniques, and cultures, we wanted to achieve that goal spontaneously by working side by side.” The beauty in this intent and exchange is paramount—and it led to Tina establishing her own studio and spending the next five years in Haiti working with other master sequin artists such as Georges Valris and Edgar Jean-Louis. They would create Vodou flags that I would have the honor of curating for display in NOMA’s Great Hall nearly twenty-five years later.

The stories that emerge from this period of her artistic practice could simply be described as “exceptionally human”—and this exceptionality is something that I felt deeply during my time working on the exhibition and the two times that I met her.

Nic Aziz, Tina Girouard, and Katie Pfohl. Aziz and Pfohl co-curated an exhibition of Girouard’s Vodou flags in 2019.

As I reflect upon Tina’s legacy, the word that appropriately comes to mind is “spirit.” It is quite antithetical to the previous word that came to mind when I first became aware of her Haiti-related work. This shift in my own thinking is a lesson within her legacy that we can all learn from. The word Vodou comes from the Fon language of the Dahomey Kingdom (within the present day African nation of Benin) and literally means “spirit”—and despite the ways in which Western societies have attempted to demonize the religion, it is one that venerably ignited the path to liberation of enslaved Africans in Saint-Domingue and established Haiti as the first independent black republic in the world.

Perhaps Tina, along with Antoine, Georges, and Edgar, and all others involved in the production of the Vodou flags within the Bondye: Between and Beyond exhibition, were not only collaboratively creating work that honored spirits within the Vodou religion but also using the works and their production as a figurative mirror to explore the essence of each other’s humanity. As we all push forward through humanity’s tribulations and convoluted compositions, these “mirrors” could be an essential place of refuge that allow us to explore the ways in which man-made constructs and conditioning have distorted our abilities to simply see, feel, and create.

Thank you for the mirror Tina.

Nic Aziz is NOMA’s Community Engagement Curator. Read more about Tina Girouard at her official website.