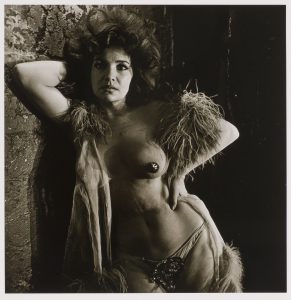

Diane Arbus (American, 1923–1971), Blaze Starr, Baltimore, 1964, Gelatin silver print, Gift of H. Russell Albright, MD, 91.528

It is often said that a portrait photograph represents some kind of exchange between the photographer and the subject, and that the resulting image, as the product of this exchange, has something from both of these figures in it. Such a description however, fails to account for the intervention of the camera—or at least the camera’s functions that are outside of the photographer’s control. There is no question, for example, that Diane Arbus is present here in the framing, the sharpness, the exposure, and even in Blaze Starr’s pose (which would surely be different in front of an operatorless camera), but the camera introduces its own particularly intrusive qualities. Arbus was a revolutionary figure in the history of photography, in part because she intuitively understood the role of the camera in these exchanges. She once described the photographic process as having “a kind of exactitude, a kind of scrutiny that we’re not normally subject to. I mean that we don’t subject each other to. We’re nicer to each other than the intervention of a camera is going to make us. It’s a little bit cold, a little bit harsh.” Unlike an encounter between two people, a photograph lingers. What might escape notice in a momentary exchange is transformed into a (semi)permanent set of declarative sentences: “This is a scar; here is a breast; and there are wrinkles on my body.” It is the static nature of the photograph that gives significance to the incidental—and that unflinchingly and perhaps cruelly submits the smallest aberration for eternal and universal judgment.

If anyone could stand up to such scrutiny it was Blaze Starr. By the time Arbus was sent to photograph her for an article in Esquire, Starr was a nationally recognized burlesque performer. Arbus made this photograph just outside the Two o’Clock Club, Starr’s home nightclub in Baltimore, but in the late 1950s Starr performed for an extended stay at the Sho-Bar on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, where she caught the eye of Governor Earl Long. Their well-known affair is often cited as a reason that Long’s wife had him committed to a mental hospital (he soon talked his way out of the facility). In New Orleans, Starr performed for then Senator John F. Kennedy and Jackie Kennedy, who were guests of Governor Long, and when Long passed away, he left Starr a bag of jewels. When a thief stole them, Starr put up a fight, resulting in the scar visible in Arbus’s photograph. Brazen, successful, and tough, Starr was every bit as blunt as Arbus’s photograph of her. In the rough social discord of the 1960s, when a sense of belonging was a highly sought-after but rarely obtained commodity, Starr almost defiantly found a place to belong in Arbus’s photograph.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.

▶ DONATE NOW