Jacob August Riis, (American, born Denmark, 1849–1914), Untitled, c. 1898, print 1941, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Milton Esterow, 99.362

When the reporter and newspaper editor Jacob Riis purchased a camera in 1888, his chief concern was to obtain pictures that would reveal a world that much of New York City tried hard to ignore: the tenement houses, streets, and back alleys that were populated by the poor and largely immigrant communities flocking to the city. Riis knew that such a revelation could only be fully achieved through the synthesis of word and image, which makes the analysis of a picture like this one—which was not published in his How the Other Half Lives (1890)—an incomplete exercise. Nevertheless, Riis’s careful choice of subject and camera placement as well as his ability to connect directly with the people he photographed often resulted, as it does here, in an image that is richly suggestive, if not precisely narrative. The two young boys occupy the back of a cart that seems to have been recently relieved of its contents, perhaps hay or feed for workhorses in the city. Maybe the cart is their charge, and they were responsible for emptying it, or perhaps they climbed into the cart to momentarily escape the cold and wind. Dirt on their cheeks, boot soles worn down to the nails, and bundled in worker’s coats and caps, they appear aged well beyond their years—men in boys’ bodies. The broken plank in the cart bed reveals the cobblestone street below. The street and the children’s faces are equidistant from the camera lens and are equally defined in the photograph, creating a visual relationship between the street and those exhausted from living on it.

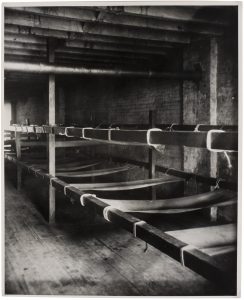

Jacob August Riis (American, born Denmark, 1849–1914), Bunks in a Seven-Cent Lodging House, Pell Street, c. 1888, Gelatin silver print, printed 1941, Image: 9 11/16 x 7 13/16 in. (24.6 x 19.8 cm); sheet: 9 7/8 x 8 1/16 in. (25.1 x 20.5 cm), Gift of Milton Esterow, 99.377

A photograph may say much about its subject but little about the labor required to create that final image. For Jacob Riis, the labor was intense—and sometimes even perilous. In the service of bringing visible, public form to the conditions of the poor, Riis sought out the most meager accommodations in dangerous neighborhoods and recorded them in harsh, contrasting light with early magnesium flashes. The technology for flash photography was then so crude that photographers occasionally scorched their hands or set their subjects on fire. Even if these problems were successfully avoided, the vast amounts of smoke produced by the pistol-fired magnesium cartridge often forced the photographer out of any enclosed area or, at the very least, obscured the subject so much that making a second negative was impossible. As a result, many of Riis’s existing prints, such as this one, are made from the sole surviving negatives made in each location.

This picture was reproduced as a line drawing in Riis’s How the Other Half Lives (1890). The accompanying text describes the differences between the prices of various lodging house accommodations. The seven-cent bunk was the least expensive licensed sleeping arrangement, although Riis cites unlicensed spaces that were even cheaper (three cents to squat in a hallway, for example). The canvas bunks pictured here were installed in a Pell Street lodging house known as Happy Jack’s Canvas Palace. Without any figure to indicate the scale of these bunks, only the width of the floorboards provides a key to the length of the cloth strips that were suspended from wooden frames that bow even without anyone to support. By focusing solely on the bunks and excluding the opposite wall, Riis depicts this claustrophobic chamber as an almost exitless space. Only the faint trace of light at the very back of the room offers any promise of something beyond the bleak present.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.

▶ DONATE NOW