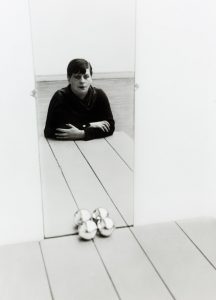

Florence Henri, Selbstportrait, 1928–1933, 8 x 11 in., Gelatin silver print on paper, Museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts and Museum Purchase Funds, 79.31.1, Florence Henri © Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genoa, Italy

What is the difference between a selfie and a self-portrait? A new exhibition drawn from NOMA’s permanent collection of photographs from the 19th through 21st centuries, opening at the St. Tammany Art Association on October 21, explores the many ways in which photographers used reflections as tools and stylistic devices, with a focus on those who chose to capture themselves and their equipment in the process. Self/Reflection: Photographs from the New Orleans Museum of Art will remain view through December 2, 2017.

Selfie culture is prevalent these days as social media platforms are flooded with thousands of images every second. While the technology to make this possible is relatively new, it could be argued that the impulse to capture/represent/reflect/portray oneself can be traced back to the very beginning of humanity. Prehistoric hand silhouettes seen in caves around the world, including Indonesia, France, Argentina, and Australia, are the first manifestations of this impulse. While it is not known if these marks were made as territorial claims, or for ceremonial purposes, or because wallpaper had yet to be invented for nearly 40,000 years, we do know by their frank existence that early humans chose to signify their physical being in that particular time and place. And modern man has only continued the inclination.

Fast forward through Ancient Egypt and Greece when artists at work were represented in hieroglyphs and vase painting, respectively; through the Renaissance when the availability of mirrors led to a boom in self-portraiture in painting, drawing, printmaking, and sculpture; and pause in 1839. Ten years after the first camera-made photograph and one year after Louis Daguerre fortuitously captured the first human in a photograph, Robert Cornelius took the first known photographic self-portrait. Using Daguerre’s method required a long exposure of the photographic plate, which allowed Cornelius time to move from behind the camera into the shot, where he would have had to stay still for several minutes. The result shows the off center bust of a young man with arms crossed staring directly out of the picture.

One can philosophize on whether it is a human compulsion to see oneself, to be seen, or to represent oneself. Indeed, arguments have been made in each case. Narcissism and vanity aside, painters and photographers alike used themselves as subjects for utilitarian purposes—as their own models they could experiment with materials, equipment, techniques, and timing. Self-portraits became means of illustrating one’s skills and advertising one’s abilities.

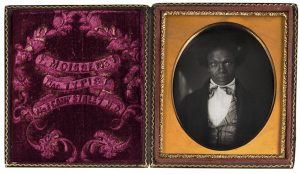

Occasionally, a photographer would capture his or her own reflection in an image out of happenstance, such as Felix Moissenet whose outline can be seen reflected in the piercing eyes of a free man of color taken in his Camp Street studio circa 1855. In other instances, artists set up the shot with the intention of capturing their own reflection in the image, as in Florence Henri’s Selbstportrait (pictured above). Once technology advanced to the point at which a photographer could see the captured image before developing it, whether coincidental or staged, the photographer was in control of creating an object that reflects himself or herself, or not. They choose to develop the image, or not.

Felix Moissenet, Freeman, c. 1855, Daguerreotype, Sixth plate, 3 1/4 x 2 3/4 in., Museum purchase, 2013.22

For those artists who chose to capture themselves within their image, there is an element of performance. How they choose to portray themselves can be seen in how an image is staged, how they are positioned, how they dress and comport themselves, what they choose to show of themselves, what they choose to show of the camera or equipment. Henri, dressed in dark colors with darkened hair and makeup heightening the contrast with her lighter surroundings sits with her arms folded and resting on a table looks straight ahead at a mirror in which she is reflected. At the base of the mirror are two small orbs that also reflect Henri and are in turn reflected in the mirror. Not seen: any vestiges of her equipment. The viewer is privy to a serious moment of introspection and contemplation, seeing what the artist saw herself but also what the artist chose to show of herself.

The intimacy that comes with seeing an individual’s point of view is also at play in this and many photographs in the exhibition. The viewer’s proximity to the artist, however direct, veiled, or distorted is important. Not only must the viewer acknowledge that proximity, but the artist has created it, expecting and inviting the scrutiny of the viewer.

A prime example of this intimacy and performance is Carrie Mae Weems’ Untitled (Man & Mirror) (1990) the first image from her Kitchen Table series in which the artist presents vignettes from the life of a fictional woman — played by the artist and staged at the artist’s own kitchen table in her apartment. Weems draws the viewer in with her direct gaze, the line of the table, which is oriented as though the viewer sits opposite her, watching as a sharply dressed man in a hat, his face concealed, leans over her provocatively. We are in her private space. It was important to Weems to make visible what was largely unseen at the time, accurate representations of women, particularly black women. Though she is portraying a character, there are still elements of autobiography that cannot be ignored or discounted.

Including works by Brassaï, Ilse Bing, Imogen Cunningham, Lee Friedlander, André Kertész, Clarence John Laughlin, and Tina Barney among others, Self/Reflection endeavors to explore the idea of self-representation and the use of reflection as device in European and American photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection.

The St. Tammany Art Association is located at 320 N. Columbia Street in Covington, Louisiana. For more information, visit the association’s website or call 985.892.8650.

–Anne C. B. Roberts, Curatorial Assistant to the Deputy Director

EVENTS

October 15, 4 – 5 pm: The St. Tammany Art Association presents Curator’s Commentary, a sneak preview and insights into Self\Reflection: Photographs from the New Orleans Museum of Art with Anne C. B. Roberts, exhibition curator. Free admission.

October 21, 5 – 9 pm: Self/Reflection officially opens to the public as part of the Fall for Art festival in downtown Covington.

November 4: The St. Tammany Art Association presents “Reflections of Me,” a children’s mirror mobile making workshop. $20 workshop fee, includes all supplies; pre‐registration required.