Though you’re unlikely to see sliced turkey with cranberry sauce, football games, or napping relatives in any of the works of art displayed at NOMA, there are hints of Thanksgiving themes to be found within our galleries. The museum will be closed on Thursday, November 23, in observation of the federal holiday, but we invite you to visit throughout the long weekend and the holiday season ahead to behold works of art that celebrate food and drink, family, togetherness, and, yes, even major sporting events.

Michael Simons, Still Life of Fruit with Lobster and Dead Game, 17th century, Oil on canvas, Bequest of Bert Piso, 81.280

Depicting a bountiful spread, this still life by Michael Simons captures an array of victuals that may look a bit different from any Thanksgiving meal Americans may know. Some notable changes may be the hare, the grapes, and, of course, the gleaming lobster to the left. However, the game birds may resemble their cousin, the turkey, once plucked, cooked, and placed on a platter. While featuring more unusual food than the standard Thanksgiving fare, this seventeenth-century painting emphasizes the preparation of a grand banquet.

Zulu People, KwaZula-Natal, South Africa, Beer vessel (ukhamba), 20th century, Earthenware, Museum purchase, Françoise Billion Richardson Collection Fund, 2001.19

In the Thanksgiving spirit of sharing, one may take inspiration from the Zulu people’s ukhamba (plural, izinkamba), vessels which were used for serving beer. A ladle, called an inkhezo, spoons the beer out of the ukhamba which is then passed around a group—although it is documented that occasionally one may drink directly from the ukhamba itself. Although izinkamba come in many shapes and sizes, varying between regions, they are consistently elaborately decorated with lines and patterned reliefs. It has been suggested that these decorations serve to add grip to the pot when it is slippery with beer—perhaps after one too many sips. This vessel embodies Thanksgiving’s tone of gathering, and perhaps participating in a drink—or two—together.

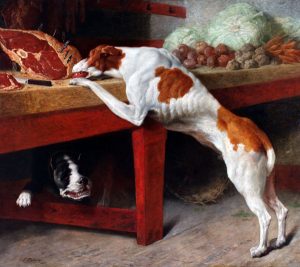

Featuring an sizable slab of meat and a pile of vegetables in the background, this painting by Paul Poincy, Dogs in the Market, captures the ravenous side of all of us when it comes time for Thanksgiving dinner. A New Orleans artist, Poincy captured portraits and places around this city in his paintings. Portraying a scene in the French Market, this work shows a moment in the height of the historic market’s popularity in a time before Winn Dixie. Historians mark that dogs frequently ran through the market, searching—or taking—food. Hopefully your dog is a little more well-mannered, and he simply begs for your turkey scraps!

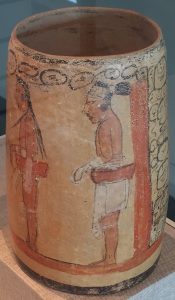

Maya Culture, Guatemala, Cylindrical Vase Depicting Four Ballgame Players, c. 600–900, Terracotta, polychrome, Museum purchase, Ella West Freeman Foundation Matching Fund, 68.16

No Thanksgiving would be complete without football; football and Thanksgiving go together like turkey and cranberry sauce. Whether you watch the game or partake in the pigskin yourself, one can argue that American football is practically a Thanksgiving ritual—although perhaps not as much as the Mayan ballgame was to the Mayans. On this Mayan vessel, four male figures pose differently, wearing traditional ballgame accessories, including yokes on hips, kneepads, and mitten-like gloves. Researches speculate that the rules of the game were to keep the hard rubber ball in play, passing from one player to another and scoring when the ball touched the court area of the opposing team—described like this, it’s more than slightly reminiscent of America’s favorite Thanksgiving game. However similar the rules might have been, the penalties for losing a game of touch football in the backyard are much less severe—losing Mayan teams were sometimes sacrificed for bountiful agriculture in the year to follow.

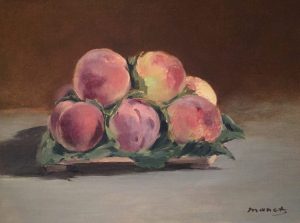

Although not typical fare on a Thanksgiving menu, there is perhaps no more Southern pride found in fruit than that within a fresh peach. In Edouard Manet’s final years, he limited himself to small-scale still life paintings of fruit and flowers, and this simple bunch of peaches is perfectly representative of that more stylized work. Plump and ready to eat, Manet’s peaches are a veritable feast in themselves.

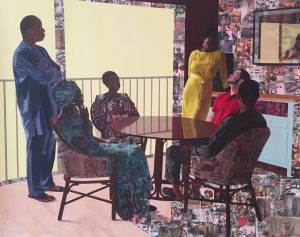

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, I Still Face You, 2015, Acrylic, color pencils, charcoal, oil transfer and college and commemorative fabric on paper, Collection of the Los Angeles Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by Holly and Albert Baril and AHAN: Studio Forum, 2015 Art Here and Now Purchase

Depicting a group sitting around a round table, with food absent, this piece invokes a deeper glimpse into the nature of meeting at a table. Born in Nigeria and now living in the United States, Njideka Akunyili Crosby merges traditional Igbo visuals and American pop culture into a conversation about shifting ideas of “home” in an increasingly global world. As Akunylili Crosby says, “I make work for diverse audiences—artists, art enthusiasts, painters, immigrants, Nigerians, Africans, non-Nigerians, [and] people from formerly colonized (and colonizing!) countries.” This universality of art can certainly be translated to a holiday celebrating the “immigrants” and “colonizing” of America—even without a feast on the table. Crosby is among the artists represented in NOMA’s Prospect.4 exhibitions.

Unidentified Artist working in Venice, The Last Supper (detail), c. 1300, Tempera and gold leaf on panel, The Samuel H. Kress Collection, 61.59

A supper of a different sort than Thanksgiving, this panel depicts the Last Supper of Christ, regarded in the Christian faith as his last meal with the twelve apostles before his crucifixion. Featuring a full table, all thirteen of the participants have bowls and drinks before them. This movement is captured in the artistic style of the eastern Mediterranean island of Crete, reflective in the dynamic, expressive strokes of the garments and white hair adorning the apostles. Following the Byzantine traditions of Crete, the meal is shown at a round table—a notable difference between thirteenth-century Italian art and later Renaissance depictions of the same scene, which change the setting to a rectangular table in favor of form and symmetry.

Giovanni Martinelli, Death Comes to the Banquet Table, c. 1630-1640, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mrs. William G. Helis, Sr., in memory of her husband, 56.57

This seventeenth-century painting depicts a grand feast rudely interrupted by an uninvited skeletal guest, accompanied by literal finger-pointing and gasps of shock. Anyone with extended family could most likely attest to the notion that oftentimes, familial Thanksgiving feasts do not run as planned, with closeted skeletons making appearances in the form of political arguments, religious disagreements, or just old family rifts. When this happens, one may wish to bury one’s face in the nearest side of stuffing—or in this painting, a delectably giant pie—but one must meet the conflict face-to-face. Speaking to a larger fear of conflict, Martinelli’s work reminds us all that not all feasts are as peaceful as we may hope them to be.

French National Porcelain Manufactory (Vincennes 1740–1756, Sèvres 1756 to present), Designed by Jean-Claude Duplessis (French, c.1695–1774), Painted by Pierre-Joseph Rosset (French, 1734–1799), Covered Tureen and Plate (Terrine du Roi), 1754–1755, Soft-paste porcelain, hand-painted and gilded, Museum purchase, William McDonald Boles and Eva Carol Boles Fund, 2000.53.a–.c

Thanksgiving is traditionally a time to pull out the fine china, polished silverware, and cherished centerpieces. NOMA’s Decorative Arts Gallery features an array of exquisite tableware, including this covered tureen and plate manufactured by the French National Porcelain Manufactory, best known by its regional home of Sèvres, from the mid-eighteenth century. Founded in 1738 as the Vincennes manufactory, the trademark porcelain became a pet project of Louis XV and his mistress Madame de Pompadour. In 1756 the factory was moved to Sèvres close to Madame de Pompadour’s Bellevue Palace and along the route to Louis XV’s residence the Palace of Versailles. Louis XV became very involved in the production of the porcelain and demanded only the finest pieces be produced. This demand probably contributed to financial difficulties experienced by the company. These financial difficulties had Louis taking over the factory and making it a royal holding until the French Revolution when it was nationalized. The state-owned manufactory continues to produce limited-edition and very expensive porcelain for global collectors.

Will Ryman, America (detail), 2013, car parts, railroad parts, cotton, computer parts, corn, coal, bullets, arrowheads, chains, shackles, wood, exterior paint, 168 x 156 x 168 inches

President Abraham Lincoln was the first to declare Thanksgiving a national holiday. On October 6, 1863, in a speech that expressed gratitude for a pivotal Union Army victory at Gettysburg, Lincoln declared that the nation would celebrate an official Thanksgiving holiday on November 26 of that year. America’s sixteenth president is heavily identified with the log cabin of his birth, a symbol of pioneer fortitude in the wilds of the North American continent. The interior of this large-scale replica of the rough-hewn abode, titled America, by artist Will Ryman, assembled on the second floor of the museum, features a kaleidoscopic assemblage of items representing the industries and economies that built the United States. Built as a chronicle of capitalism in America, this structure features everything from cigarettes to coal and cotton to candy—all painted a luminous shade of gold.

David Johnson, editor of museum publications, and Katelyn Fecteau, editorial intern, contributed to this feature.