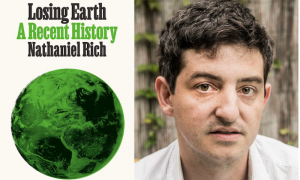

The 1970s and ’80s proved to be pivotal decades in scientific study of climate change — and opportunities to raise public awareness and enact mitigating policies. New Orleans-based writer Nathaniel Rich takes an in-depth look at the failure to act and efforts to dismiss warnings from scientists and activists in his book Losing Earth: A Recent History, published in 2019. In conjunction with exhibitions at NOMA that address environmental issues—including Tina Freeman: Lamentations and Inventing Acadia: Painting and Place in Louisiana—Rich will discuss his research as part of Friday Nights at NOMA on January 17, at 6:30 pm, followed by a book signing in the Museum Shop. Rich will be joined in conversation by Mark Davis, founding director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Law and Policy.

In advance of the talk, Rich spoke with NOMA Magazine.

What drew you to the subject of climate change?

I came to write about climate change not from any activist impulse but out of a frustration with the dominant writing on the subject. I didn’t think that anybody had written very deeply about what seemed to me the heart of the story: the human dimension of the problem.

Climate change is not merely the most important issue of our age, but the story of our age, even of our civilization—nature’s backlash against the rapid progress enjoyed by our species, by nearly every metric conceivable, during the last two centuries. Yet much of the writing on climate has been narrow, unimaginative, repetitive. There has been excellent reporting about the science, the fossil-fuel industry’s disinformation campaigns, the economic questions, the technology available to us, the apocalyptic projections. We need that journalism and could use a lot more of it. But few serious writers have examined the larger human questions raised by climate change. For instance: How does a sentient person alive now live with the knowledge that we’ve devised a mechanism of self-annihilation? Will future generations be satisfied with the justifications we offer today for inaction? Even as we push for action today, how do we make sense of our past failures to act? How do we begin to make sense of our own complicity, however reluctant, in this nightmare?

You claim that there is prevalent “public amnesia” about the history of climate change. Please explain, and why does this continue to stymie efforts to address extreme weather?

These are the questions that drove me to tell the intimate stories of those who first grappled with them. The book’s main figures—Rafe Pomerance, James Hansen—were not only the first people to try to develop political solutions to climate change, but the first to ask what the crisis might mean for their own futures and the lives of those they loved.

Public amnesia has been a stated goal of climate disinformationists for decades; as long ago as the early 1990s, Exxon spokesmen were insisting that the science was too uncertain to serve as the basis of regulatory policy, even though its own scientists had understood perfectly the science of global warming since the 1950s. But even the most well-intentioned leaders of the movement to curb carbon emissions today still often fail to recognize how old a problem this is. I think of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez complaining how the “United States government knew that climate change was real and human-caused in 1989, the year I was born.” But our government has known about it, at the highest levels, since the 1950s. There were major features in Life and Time that decade about the problem, articles in the New York Times and other newspapers, it was even featured in the most widely-watched children’s show in the nation. This problem has been us for a long time. What’s new is the idea that it’s a new problem.

ABOUT NATHANIEL RICH

Nathaniel Rich is the author of three novels: King Zeno (MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018); Odds Against Tomorrow (FSG, 2013); and The Mayor’s Tongue (Riverhead, 2008). Losing Earth: A Recent History was published in April 2019 by MCD/Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Rich’s short fiction has been published by McSweeney’s, Vice, the Virginia Quarterly Review, and the American Scholar; the stories “The Northeast Kingdom” and “Blue Rock” were both finalists for the National Magazine Award for Fiction, and the latter was awarded the 2017 Emily Clark Balch Prize for Fiction. Rich served as Fiction Editor of the Paris Review between 2005 and 2010.

Rich is a writer-at-large for the New York Times Magazine; his essays on literature appear regularly in the Atlantic, Harper’s, and the New York Review of Books. His reported pieces have appeared in various anthologies, including the Best American Nonrequired Reading and the Best American Science and Nature Writing.

In 2005 he published a work of film criticism, San Francisco Noir: The City in Film Noir from 1940 to the Present, which Martin Scorsese called “a fascinating work of criticism disguised as a guided tour around a great city.”

NOMA members inspire the love of art in every visitor who walks into the Great Hall or through the gates of the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden.

In addition to enjoying benefits like special members’ previews of exhibitions, free wellness classes surrounded by sculptures, and a complimentary subscription to NOMA Magazine, our members enable schoolchildren to discover the Old Masters, community members to engage with world-class art and local artists, and NOMA’s curators to present innovative and provocative exhibitions year after year.

JOIN TODAY