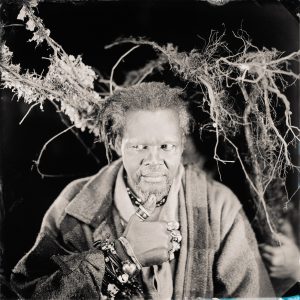

Timothy Duffy (American, b. 1969), Ironing Board Sam (Sammie Moore), 9th Wonder of the World, Hillsboro, NC, 2015, Tintype, 14 x 14 in., Courtesy of the artist

The tintype portraits of musicians by Timothy Duffy (American, b. 1963) are a thoroughly American enterprise: his choice of materials aligns with and challenges a distinctly American history of photography, while his subjects represent one of the most important musical legacies in the United States. Duffy’s photographs have a distinct “American-ness” and his choice of subjects represent the often overlooked but rightful creators, custodians, purveyors, and performers of American music.

The tintype photograph was first patented in the United States in 1856, and its common name, “tintype,” was a popular adaptation of the more precise “ferrotype,” as the images are produced on sheets of iron, not tin. Perhaps most importantly, the tintype is a direct positive process, meaning that each image is unique, and is produced directly inside the camera. It is also the first photographic medium in which African Americans appear in any great number. The New Orleans Museum of Art has almost sixty such tintypes.

The rise in popularity of the tintype coincided with the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the Civil War. Tintypes were inexpensive and they were often produced by itinerant makers who would briefly set up their wagon in a town, making it common to encounter the process in both urban and rural areas. The tintype, therefore, embodies particular visual histories of both class and race. It is also arguably the most anonymous form of photography in the nineteenth-century. Its quick mode of production left little time for fussy cases that might have identified the maker, and there was often no need to identify the person in the photograph. Thus the vast archive of American tintypes produced between the late 1850s and the 1930s is a frustratingly silent visual census of a generation of American people: their shadows immortalized, but the substance of their stories notably absent.

Whereas the story of the tintype was one of anonymity, Timothy Duffy seeks to make it about authorship. Not only are his pictures decidedly the products of an artist, they are also pictures of artists. For the past several years, Duffy has sought out the makers of American roots music, looking to set the record straight, or at least make sure the record exists. If the previous century of tintype image-making was a missed opportunity, Duffy is determined to record this history as it happens, producing a masterful set of tintypes which ensures that this generation will be able to speak to future ones.

In his years of making tintypes, Duffy has embraced their brilliance, their eccentricities, and even their faults. Much like the improvisational qualities of the music that his subjects play, the best tintypes often result from incidental effects of the process—drying too quickly, oversensitivity, slight ripples in the surface of the chemistry. Duffy welcomes these as flourishes or nuances that elevate the image beyond the realm of technical achievement. Each of Duffy’s tintypes was produced inside a large camera, which makes possible an incredible amount of detail, palpably tracing lines etched in skin. It is an intrusive level of detail, or at least would seem so if the musicians did not confront the camera as forcefully as it confronts them. Duffy is often quick to point out his subjects’ role in the production of these images, referring to them as collaborators. Indeed, they often seem completely self-determined in the resulting images. Ironing Board Sam almost leaps off the plate, playing directly to the camera and by extension us as viewers, with his sparkling jacket made even more brilliant on the surface of the reflective metal plate. And Lonnie Holley performs for the camera, glancing suspiciously to the side, and clutching his chest defensively against the threat of a “White Man Stealing My Roots,” as he asserts in the title.

Timothy Duffy, Lonnie Holley, White Man Stealing My Roots, Hillsboro, NC, 2017, Tintype, 14 x 14 in., Courtesy of the artist

Holley’s tableau cuts to the heart of the issue that Duffy and his collaborators seek to address: despite the importance of these musicians, and the national legacy they represent, many remain little known, often outpaced by other popular performers who have built their own careers on top of the “roots” of these musicians and their ancestors. Duffy’s tintypes give them a visible presence, but in his other endeavor, as Director of the Music Maker Relief Foundation, he also finds ways to provide support for them, both financial and promotional. In all aspects of his life, he is dedicated to the preservation of both the shadow and the substance of these figures. In making these photographs, in compelling us to look closer, know the faces, and learn the names, Duffy has enlisted one American tradition, the tintype, in the service of honoring another.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs

Timothy Duffy: Blue Muse will be on view in the Templemann Galleries from April 25 through August 4.