NOMA’s vast collection of photography includes numerous examples of religious practices captured on film. Featured here are eight selections —ranging from an evangelistic preacher in 1930s-era Harlem to Muslim women in mid-century Kashmir — chosen by Brian Piper, Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator for Photography, and Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings.

Between World Wars I and II, James Van Der Zee was one of the most popular photographers in Harlem, New York. Known primarily for his portraits, Van Der Zee also worked for a wide range of clients outside of his studio, including a variety of Harlem’s diverse faith communities. Daddy Grace, born Marcelino Manuel de Graca, founded the United House of Prayer for All People in 1919. As leader of this independent Christian church, Grace became well-known for his charismatic style of evangelism and stories of faith healing. Mordecai Herman oversaw the Moorish Zionist Temple, one of the earliest Black Hebrew groups in New York. Believing they were descendants of the biblical Israelites, members of this Temple fused traditional Jewish and Christian elements with early Pan-African nationalism.

Both of these pictures (click on the image to enlarge) show off Van Der Zee’s virtuosity and creativity as a photographer. He captures Rabbi Herman leading a service through his temple’s window, famed by Hebrew lettering and American and Israeli flags. The yellow that remains in the center, is from where Van Der Zee (or an employee) hand-colored the candles and lightbulb inside the window. Daddy Grace is a fine example of Van Der Zee’s use of compound negatives. Here, he photographed a biblical illustration separately and then overlaid that negative with his portrait of Grace, printing them as one seemingly magical image, that likely enhanced Grace’s legend. —Brian Piper

Linnaeus Tripe (British, 1822–1902) , Triviar, Ghats, March–April 1858, Albumen print from a waxed paper negative, 25.1 x 38.1 cm., Museum purchase, 87.36

As a captain in the East India Company army, Linnaeus Tripe produced some of the earliest photographs of India and Burma in the 1850s. Many of his photographs were ultimately set into a series of lavish bound albums that comprised a visual survey of these locations. This photograph, which Tripe made in Triviar (Trivady), a town near Tanjore, shows the “ghats” or sacred bathing places and entry points alongside a body of water. Although these photographs are today some of the best documents of the structures that existed at the time, it is important to remember that they were produced in service of a foreign government that sought to control these places and the people that lived there. —Russell Lord

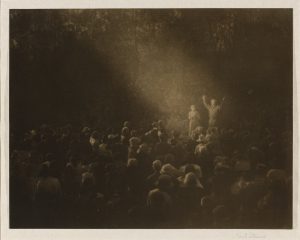

Karl Struss (American, 1886–1981), The Faith Healer, 1921, Gum over platinum print, Sheet: 10 5/16 x 13 3/16 in. (26.2 x 33.5 cm); mount: 14 5/16 x 16 5/16 in. (36.6 x 41.4 cm), Museum purchase, 1977 Acquisition Fund Drive, 77.18

Born and raised in New York City, where he studied under Clarence H. White at his photography school, Karl Struss was an active member of the pictorialist photography community, which favored soft, dark, and carefully crafted prints, like this example. In 1919, Struss moved to Hollywood, where he became one of the leading early cinematographers, winning one of the first Academy Awards for cinematography for his work on F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927). Fortunately for Struss, the fledgling field of cinematography still had a proclivity for the expressionist strain of moving pictures that emerged from Germany. This aesthetic perfectly matched his approach to photography, as this film still for an unidentified project reveals. Isolated by a sharp beam of light, “the faith healer” is presented ambiguously: the loyalty he inspires, attested by the enormous crowd presumably on hand to witness his power, is both troubling and potent. It is likely that Struss made this picture as a kind of film still on the set of the 1921 silent movie The Faith Healer, now lost. Karl Struss, along with his teacher, Clarence White, co-curated the first ever photography exhibition at NOMA in 1918. —Russell Lord

Unidentified photographer, Je Suis L’imaculee Conception, c. 1885, Albumen print, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Prakapas, 86.369.151

This photograph depicts the Grotto of Massabielle in Lourdes, France, where in 1858 Bernadette Soubrious claimed to witness an apparition of the Virgin Mary seventeen times. The vision implored Soubrious to drink water from a small spring in the cave and then asked for a chapel to be built. The vision told the young woman “I am the immaculate conception.” Soon after, the grotto was established as a shrine and a Catholic sanctuary was built on the grounds. The Vatican canonized Saint Bernadette in 1933, and replicas of the Lourdes grotto proliferated around the world (several exist in New Orleans). Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims still visit the grotto every year, many to drink the spring water which is believed to have miraculous healing properties. In this photograph, several supplicants kneel in prayer. Hundreds of crutches, presumably from sick or infirm visitors line the walls of the grotto, a grim reminder of our fragile health but also a testament to the great religious faith that draws people to Lourdes.

In the late nineteenth century, inexpensive albumen prints like this were commercially produced in large numbers and easily distributed around the world. Religious-themed photographs were among the most popular. A visitor to Lourdes could purchase one as a souvenir, or you could order one from a photographer’s catalog without ever making the pilgrimage. For a person of faith, viewing this photograph in an album or on the mantle could call up those same feelings of hope and reverence across time and space. —Brian Piper,

Roman Vishniac (American, born Russia, 1897–1990), Man Soaking Bread at Water Pump, c. 1938, Gelatin silver print, Image: 9 1/2 x 7 9/16 in. (24.1 x 19.2 cm); sheet: 9 13/16 x 8 in. (24.9 x 20.3 cm), Museum purchase, 74.95

In 1935, Roman Vishniac was hired by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, a leading humanitarian assistance organization, to photograph Jewish communities throughout Eastern Europe. Over the next few years, Vishniac built an extensive visual record of life in these communities, chronicling poverty in major urban centers and small villages alike. Although many of these communities were centuries old when Vishniac photographed them, his body of work would soon prove to be the only comprehensive document at the very end of their existence, as the Nazis systematically eradicated Jewish life in Europe.

Here, Vishniac captures a poignant gesture: a man soaking a piece of hard, stale bread at a water pump just to render it edible. The stones and cement around his feet are stained dark from the water and register clearly in the photographic negative, while the rest of the street and much of the background is blown out by the harsh light of day. The result is a portrait of isolation. It is now almost impossible to separate these images from the history that followed them. What in another context might be only a simple, if powerful, document of impoverished life becomes a haunting elegy for a life already circumscribed by the specter of death. —Russell Lord

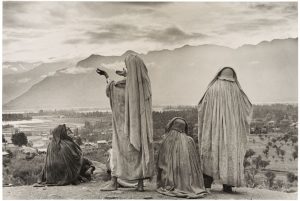

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908–2004), Srinagar, Kashmir, 1948, Gelatin silver print, 9 9/16 x 14 3/8 in. (24.3 x 36.5 cm), Museum purchase, Women’s Volunteer Committee Fund, 73.222

Here, a group of Muslim women pray on Hari Parbat, a holy site overlooking the Indian city of Srinagar, while the sun rises behind the Himalayas. The hill is a nexus point for many religions: a Hindu temple, multiple mosques, and gurdwara (places of assembly and worship for Sikhs) are all located there. Isolating the group of figures against the mountains, Henri Cartier-Bresson arrested the moment when one of the women reaches out, a gesture of prayer that looks as if she is releasing the distant clouds into the air like doves. A month after making this picture, Cartier-Bresson met with Mahatma Gandhi to cover the breaking of his six day fast, and ninety minutes after that meeting, Gandhi was assassinated.

The word “immediacy” is often invoked in discussions about photography. It is frequently found as a descriptor for the work of Cartier-Bresson, and perhaps this is not surprising: “immediacy,” used loosely, connotes the same sense of urgent temporality as does the famous “decisive moment” conception of photography that is usually applied to Cartier-Bresson’s work (despite the fact that he never used the term to describe it). Used precisely, however, “immediacy” refers to something that is unmediated, a direct engagement with a thing or an experience. As convincing as any photograph of a thing might be, it is still a mediated version of that thing, which is to say that a photograph might seem to possess a sense of immediacy, but that perception is nothing but an alluring deception.

Consider the present image, for example. Let us assume for a moment, even if it is not true, that we know nothing about it. Then let us consider the distance between what little we can know for certain from the image and how much more we would know if we were actually there. We can make several assumptions about the isolated moment that the photograph represents, but it lacks the before and after that actual experience would provide. In this case, for Cartier-Bresson, that experience included the beginnings of the Indo-Pakistani War; arduous travel by boat, plane, train, bus, military convoy, and foot; and days of rain and flooding. It was, in other words, much noisier and more violent than the quiet, contemplative image that he managed to excise from that experience would suggest—here, a group of Muslim women pray on Hari Parbat, a holy site overlooking Srinagar, while the sun rises behind the Himalayas.

Of course, Cartier-Bresson never intended for his photographs to fully articulate their own contexts; rather, his goal was to make pictures, like this one, that can convey a sense of humanism beyond the facts that brought his images into being. While this photograph may remain mute as to the social and political backdrop of its subjects, Cartier-Bresson’s intuitive attention to the alignment of elements in front of the camera results in a picture that is rich with suggestion. —Russell Lord

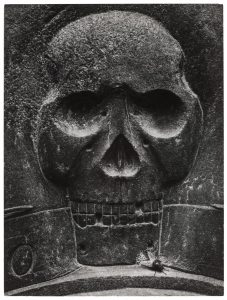

Ansel Adams (American, 1902–1984), Gravestone Detail, Concord, Massachusetts, ca. 1960, Gelatin silver print, 9 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (24.8 x 18.4 cm), Gift of Mrs. P. Roussel Norman, 86.319.1

Ansel Adams is, in one way, a victim of his own success. His best-known images, sensuous and majestic representations of the American West, issued in a variety of formats, have been the subject of multiple catalogs, and remain widely distributed in calendars still today. One photograph even adorned a 3-pound can of Hills Brothers coffee in the 1960s. The problem is not with the commercial success of these images, but rather the way in which their renown has completely eclipsed everything else he did. For example, throughout his career, Adams was apparently always interested in gravestones. Beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s, Adams photographed old carved headstones in cemeteries from California to New England. He viewed these markers as “profoundly human,” by which he meant to describe the deep personal connection that must have existed between those who installed the stones and those they commemorate. He also, however, valued the craft of the stone carvers, calling it “folk art” and seeing yet another profoundly human dimension in the quality of the work and how that work expressed cultural traditions about life and death. But even within his cemetery photographs, this particular image is an outlier: Adams was careful to explain that his interest in these scenes was not motivated by a macabre obsession with death in and of itself. As a result, his headstone pictures tend to be beautiful but literal descriptions of the stone and its carving and not overtly symbolic, as this one appears to be. A dead fly rests beneath a skull whose expression is more contemplative than frightening, as if this were a twentieth-century meditation on a very common theme: death and the fleeting nature of life.

Such an interpretation might veer too close to metaphor for Adams, but he was sympathetic to its conclusion. For him, the gravestones were not only about what remained but also about what once was. He described these markers as the “closest link I know to the past” and felt they provided “contact with past humanity.” Despite their importance to him, these gravestone photographs remain relatively unknown compared to his landscapes, and yet Adams’s interest in both subjects may originate from a similar concern for humanity’s place in the world. The experience of a vast landscape is not unlike that of considering the deceased through the markers they leave behind. Both make explicit our own limited dimension, in either space or time. To marginalize Adams’s photographs of gravestones, therefore, is to obscure a part of him that informs the rest. Somewhere between the cemetery and the mountain, the humanist and the naturalist collide. —Russell Lord

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

Your gift to NOMA provides critical support for the museum and plays an integral role in all that the museum does, from presenting groundbreaking exhibitions to offering arts-integrated education programs to students across the region.