In 1908, the recently chartered National Child Labor Council (NCLC) hired Lewis W. Hine to make photographs to aid efforts to end exploitative and abusive child labor practices. Hine had trained as a sociologist, and while teaching at the Ethical Culture School in New York, Hine came to believe in the power of photographs to document social issues and encourage reform. The NCLC focused on garnering support from the white elite and middle classes, most of whom were unfamiliar with the realities of industrial work.

Hine traveled throughout the country photographing children working long hours and at dangerous tasks in textile mills, factories, meatpacking plants, and mines. Hine’s own work was dangerous, as he was traveling in states resistant to protections for child workers and into facilities where bosses did not want poor working conditions exposed. The photographer often adopted disguises or concocted stories to photograph and then interview workers. Hine knew that precise and accurate details would have the most efficacy in bringing about protections for young workers. The results were straightforward, un-retouched photographs with a modern sensibility. They helped set a standard for the documentary photography tradition that exploded in the United States between the World Wars.

Lewis W. Hine, (American, 1874–1940), Johnnie, a nine-year old oyster shucker, 1911. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Women’s Volunteer Committee Fund and Dr. Ralph Fabacher, 73.122.

The photographer made a trip to the Gulf states in 1911, and investigated working conditions in the seafood industry in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. In the 1890s, advances in railroads, canning, and ice-making greatly expanded the market for Gulf Coast seafood, and companies encouraged immigrants from Eastern Europe to move to the region (often via Baltimore) for the winter season with their entire families. Any child labor protections each state had in place were routinely ignored or went unenforced, and children began cleaning shrimp and oysters in industrial facilities as soon as they were able.

In Dunbar, Louisiana, Hine used his camera to reveal children packed shoulder to shoulder and working feverishly in an oyster packing plant. The titular subject of the photograph above, Johnnie, aged 9, has to stand on the rail just to reach the oysters to shuck. Hine also annotated each image he made, including details like the hours worked (3:30 am to 5:30 pm) and the number of “pots” of seafood each child was expected to process each day. This photograph also features the “boss of the shucking shed” with a pipe and bowler hat in the background. This man offered that “I have to lie to ‘em,” to entice workers from Baltimore, an attitude that fits his lurking posture here.

Lewis W. Hine (American, 1874-1940), Maud Daly, five years old. Grace Daly, three years old, 1911. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Women’s Volunteer Committee Fund and Dr. Ralph Fabacher, 73.128.

At other times, Hine waited until managers went to lunch or young laborers went home for the day to make his surreptitious portraits. Hine’s caption for this second picture reads, in full:

Maud Daly, five years old. Grace Daly, three years old. Pick shrimp at the Peerless Oyster Co. Their mother said they both help, and their sister said the little one worked fastest. Many little ones like them work here. Location: Bay St. Louis, Mississippi

Impressive for its clarity and texture, the success of this portrait also depended on the conflation of the concepts of childhood and innocence, an idealization that first emerged in the nineteenth century. At the time of this photograph, that belief only extended to white children in the minds of the NCLC’s supporters, and the conflation of all three ideas—childhood, innocence, whiteness—made this photograph a potent image for the organization. The sentimental juxtaposition of these girls’ incredibly young faces with their dirty clothes and worn shoes made what the NCLC considered a moral case for eliminating child labor.

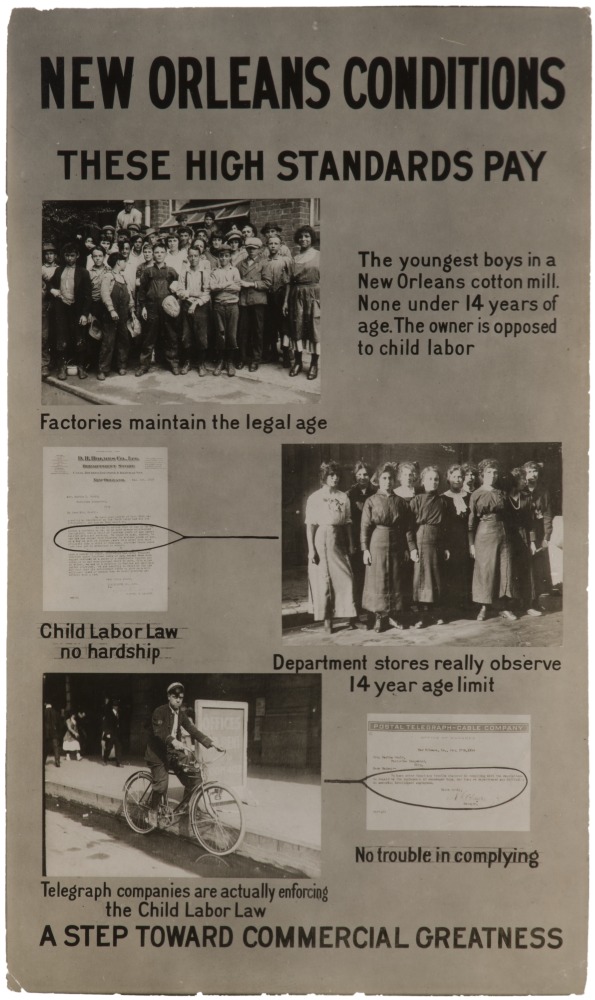

Hine also made photographs of instances that the NCLC viewed as success, where child labor laws were successfully in place and enforced. The photographs in this panel were made in New Orleans. In the city, Hine found department stores, a telegraph operator, and a cotton mill employing no children under the age of fourteen, in compliance with the current law. Contrasted with Hine’s photos of young seafood workers, these children appear clean and in good spirits.

Lewis W. Hine (American, 1874-1940), These High Standards Pay, c. 1911. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Joshua Mann Pailet, 2000.623.

This object in NOMA’s collection is actually a four-by-six-inch photographic print of a much larger poster that Hine made by combining his own images with text and graphic elements. For this display, signed testimonies are reproduced as a reassurance for the managerial and capital classes that following labor laws will assuredly lead to “commercial greatness.” Hine created many panels like these—showing both poor conditions and high standards (that pay)—and organized them into exhibitions that toured widely, in an effort to illustrate how stronger national labor protections would improve life in the United States.

—Brian Piper, Assistant Curator of Photographs

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts—now more than ever. Your gift makes a direct and immediate impact as we plan exciting new exhibitions, organize insightful programs in the museum and Besthoff Sculpture Garden, and develop new ways for you to #ExploreNOMA.