If the Authorities Ask, They Are Just Decorative

Farberware (New York, New York, founded 1900), “Bubble” Cocktail Shaker and Cup, c. 1930. Chrome-plated metal, wood. Gift from the George R. Kravis II Collection, 2019.8.64.1–3.

The distinctive swishing, clinking sound of ice cubes and liquid jostling inside a cocktail shaker is a joyful part of mixing up a daiquiri or a French 75. NOMA’s collection includes two American chrome cocktail shakers that date from around 1930, during an era known for the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. But with some irony, the Prohibition era also saw Americans drinking more distilled liquor than they ever had before.

Prohibition was a nationwide ban on the production, importation, transportation, or sale of alcoholic beverages. It lasted from 1920, when the 18th Amendment was made to the US Constitution, to 1933, with its repeal and the 21st Amendment. A common idea is that cocktail mixed drinks became popular during this time to disguise the bad taste of illegal “bathtub” gin, but as with all things, the truth is both more complicated and a little more dull.

New Orleans drinking culture historian Elizabeth Pearce, owner of Drink & Learn and host of the Drink & Learn podcast, notes that the broad American cultural shift around drinking in the 1920s was not necessarily the invention of new cocktails, and the popular underground cocktails were not necessarily even American. “Yes, there were drinks invented during prohibition but most of the classic Prohibition-era cocktails we think of were created long before. A 1920s gin cocktail the ‘Last Word’ was invented in 1915, before Prohibition. The white rum ‘Mary Pickford’ drink was invented in Cuba when the actress visited there, and ‘The Bee’s Knees’ was created at the Hotel Ritz in Paris, presumably with very good gin from England.”

According to Smithsonian Magazine, prior to Prohibition distilled spirits accounted for less than 40 percent of the alcohol consumed in America. By repeal in 1933, spirits made up more than 75 percent of alcohol sales. With that marked shift from Americans drinking beer and wine to drinking Sazeracs and martinis came the resurrection of old recipes for mixing liquor and the proliferation of everyday bar equipment for preparing and serving cocktails.

“There was an explosion of people making drinks at home,” Pearce notes. “We watch movies of people going to speakeasies and think that was the only way that people were drinking in the 1920s, but in fact one of the ways you could legally drink was in your home, consuming liquor that you purchased before the National Prohibition Act went into effect.”

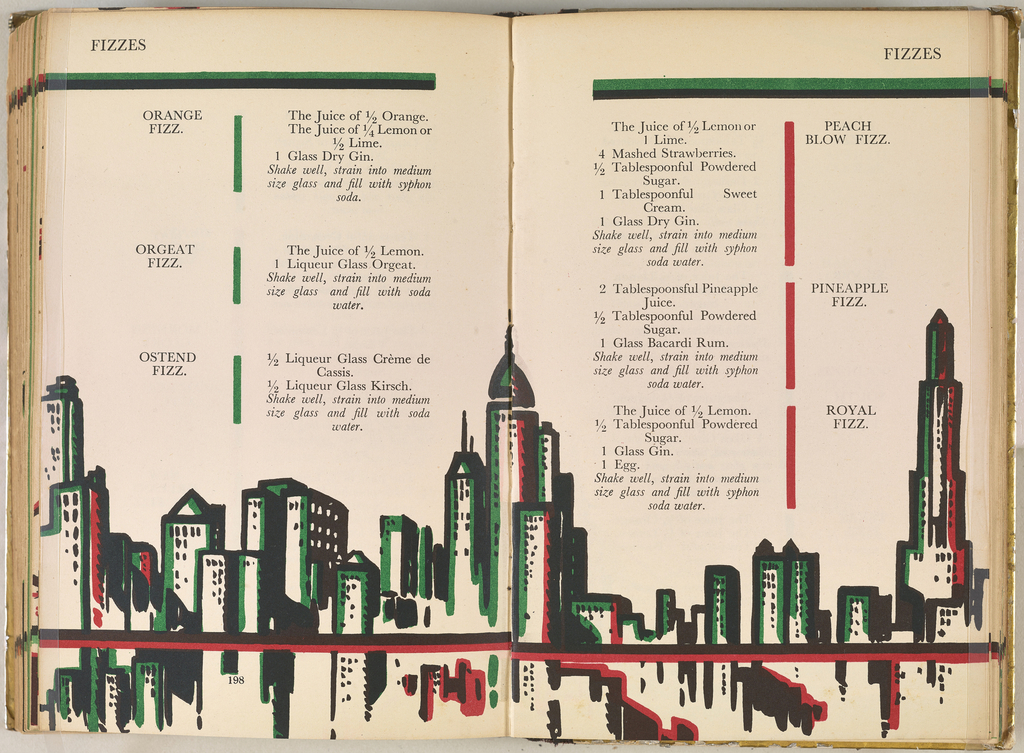

Two-page recipe spread in Harry Craddock’s The Savoy Cocktail Book, 1930. Smithsonian Libraries, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Library, Gift of George R. Kravis II.

Well-known mixologists like Harry Craddock of the Savoy Hotel in London published recipe books to aid bartenders working at home or in new private clubs. Craddock’s The Savoy Cocktail Book collection of 750 cocktails recipes was first published in 1930 and is still in print today.

Once alcohol consumption moved into American homes, Pearce notes there was a changing acceptance to women imbibing alongside men. “Coupled with the passage of women’s right to vote in 1920, all women began to enjoy more freedoms…It wasn’t just flappers. And if you are the hostess, you want to offer something delicious.” Prohibition-era newspapers could not legally publish cocktail recipes, but Pearce notes that leading up to and just after prohibition, newspaper women’s sections advised readers on how to make a Manhattan or other popular drinks.

Chase Brass and Copper Company (Waterbury, Connecticut, founded 1837), Howard F. Reichenbach, designer (American, 1901–1959), “Gaiety” Cocktail Shaker, 1933–1937. Chrome-plated and enameled brass, Bakelite plastic. Gift from the George R. Kravis II Collection, 2019.8.28.a–c.

Those Prohibition-era 1920s newspaper advertisements also indicated that people were still buying barware, and Pearce notes, “It couldn’t be just decorative!” Of the two chrome cocktail shakers currently on view at NOMA, we know that one was produced by Chase Brass & Copper in 1933, that is, not until legally after the repeal of Prohibition. The production dates on the other shaker, pictured at the top of this article, are unclear. This well-known Farberware c. 1930 Art Deco “Bubble” cocktail shaker is generally included among those intentionally overly-decorative bar equipment that could arguably be considered ornament, if questioned by authorities or temperance advocates, and not only utilitarian. Other illicit barware took the form of penguin and lighthouse shakers, or even a flask fully disguised as opera glasses.

Chase’s “Gaiety” cocktail shaker was designed in 1933, post Prohibition, in the Specialty Division of a company mainly known as an industrial metal producer, not a purveyor of fine home goods. Their Specialty group was formed in 1928 to allow industrial designers like Howard Reichenbach room to be more creative and responsive to the desires of the market. During the 1930s economic depression, these designers combined fresh “Modern” styling with intentionally low prices to broaden the types of domestic goods made with modest brass, chrome, and copper.

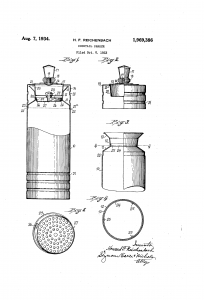

During his time at Chase, Reichenbach established eighteen U.S. patents to his name, including designs for lamps, a lipstick applicator tube, and this 1933 cocktail shaker. In his written patent application he makes the claim:

Howard F. Reichenbach, inventor; The Chase Companies, Inc, assigner. Cocktail Shaker. US Patent 1,969,386. October 6, 1933.

My invention relates to an improvement in cocktail shakers, the object being to produce a shaker of superior convenience, appearance and effectiveness, constructed with particular reference to preventing the escape of any fluid, no matter how violently it is shaken.

Reichenbach didn’t invent the shaker form, just added his own design twist. Much like when today’s bartenders put a trendy lavender or chili pepper spin on a gin, tequila, or rum drink, they are adding to the long history of carefully crafted cocktails.

The 1930s “Bubble” and “Gaiety” cocktail shakers are currently on view in an installation at Café NOMA. The display highlights cross-cultural museum collection objects related to dining and food, including French wine bottles, English glass champagne flutes, Chinese porcelain punch bowls, and African palm wine containers.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts & Design

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.