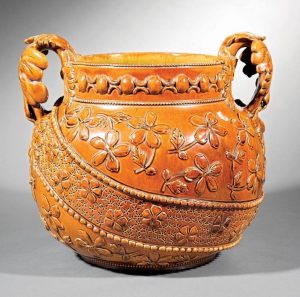

New Orleans Art Pottery (New Orleans, c. 1887–1893), Thrown by Joseph Fortune Meyer (American, 1848–1931) and George E. Ohr (American, 1857–1918), Jardinière, c. 1890. Earthenware, glazed; 16 1/2 h x 18 inch diameter.Museum purchase, Mervin and Maxine Mock Morais Fund and Partial Gift of Jean R. Heid, 2018.61.

NOMA recently acquired a jardinière that was crafted around 1890 at the short-lived New Orleans Art Pottery. Though this small operation only produced pots for a few years, it carries outsized significance as one of the earliest American art potteries and an important precursor to the cherished pottery that thrived for decades at New Orleans’s Newcomb College. The New Orleans Art Pottery specialized in crude but sophisticated utilitarian objects–architectural tiles or outdoor planters like this jardinière–so many examples were discarded after being worn, broken, or unrecognized as hand-thrown pieces of New Orleans history. With so much of their work lost to time, we celebrate this new addition to NOMA’s permanent collection as a rare piece of New Orleans art history.

A pair of New England brothers named Ellsworth and William Woodward came to this city to run the creative programs at the 1884 New Orleans World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. Their public art classes were so incredibly popular that, after the close of the fair, the brothers were hired as professors by Tulane University. In addition to art instruction for women at the new Newcomb College (the 1886 sister college to Tulane University), the Woodward brothers helped establish the “Women’s Decorative Art League” in the late 1880s. A December 1887 New Orleans Daily Picayunearticle called the league an “association of 75 or more women, brainy and plucky, who are determined to establish themselves as decorators.”

Housed in the Central Business District at 249 Baronne Street, the Women’s Decorative Art League offered instruction in a variety of practical arts, including in artistic ceramics. Aligning with the emerging Arts & Crafts Movement, which called for local materials and individual craftsmanship in opposition to industrial manufacture, “the products of the league will be entirely home industry, as they will grind their own clay, do their own modeling, designing and decorating.” This league’s pottery operated under the name “New Orleans Art Pottery” until 1890, after which it was called the “Art League Pottery Club.” NOMA’s jardinière is scratched on the bottom “The Pottery Club / 249 Baronne St / N.O. La.”

The Daily Picayune article notes that “an experienced potter has been secured, who will go to work as soon as possible, making the rough flowers pots.”That potter was the Biloxi native Joseph Fortune Meyer. To assist with the logistics, Meyer hired for a short time his friend and protégé George E. Ohr, a now-famous artist who later carved out his own place in history as the “mad potter of Biloxi” with outrageously creative ceramics. At the New Orleans Art Pottery, Meyer and Ohr turned out large-scale, classically-shaped low-fired utilitarian ceramics, just like this jardinière, which were decorated with punch and scratch designs and applied ornament by the female students of the art league.

Reportedly, the women’s art league sent forty examples of their work in a variety of medium to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, but not much is known about the enterprise after that date. The idea of a pottery as central to the practical education of women in the arts, however, had taken root in New Orleans. Ellsworth Woodward appealed to the Newcomb College president for the addition of a ceramics program, celebrating clay as the ideal artistic material, for”the possibilities underlying native raw materials when trained talent takes it in hand and stamps it for beauty and use.”By 1894, Woodward’s suggestion was a reality, as Newcomb constructed a special art building equipped with facilities for firing and glazing ceramics. Expert potter Joseph Fortune Meyer was brought on to the staff, running the famous Newcomb College pottery from 1897 to 1927.

NOMA’s rustic jardinière reminds us again of the rich artistic scene in New Orleans at the turn of the century. The experimentation in giving young women a practical education in interconnecting art, craft, and manufacturing of ceramics at the New Orleans Art Pottery laid the foundations for one of this city’s most enduring contributions to American arts, the superb handmade Arts & Crafts pottery made by the women of Newcomb College.

—Mel Buchanan, RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design