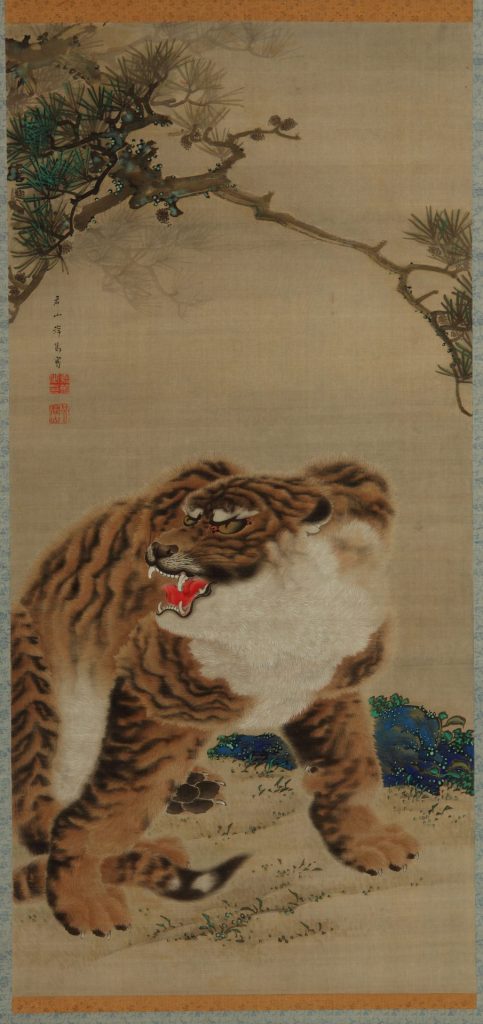

Kishi Gantoku (Japanese, late 19th century), Tiger Beneath a Pine Tree. Ink and color on silk. Gift of MaryAnne and Howard Rogers in Honor of Kurt Gitter, M.D., and Alice Rae Yelen, 2011.38.

February 1 marks the beginning of the Year of the Tiger.

For China, Vietnam, and other countries across East and Southeast Asia, the Lunar New Year—sometimes also called the Chinese New Year—is one of the most important celebrations on the calendar. Following the traditional lunisolar calendar, the new year starts sometime between late January and early March.

While the new year has been celebrated on January 1 in Japan since 1873—due to a shift to the Gregorian calendar—there are several earlier examples of works in NOMA’s Japanese art collection celebrating the Lunar New Year.

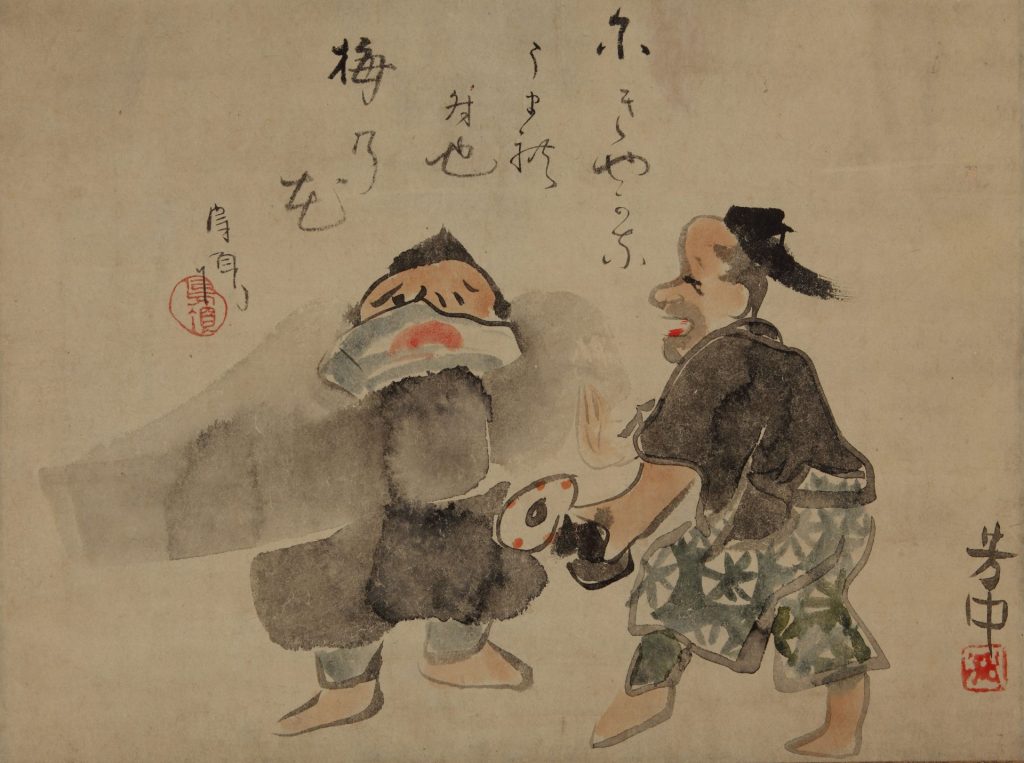

Nakamura Hochu (Japanese, active 1790-1813), New Year’s Revelers. Ink and color on paper. Women’s Volunteer Committee Fund in memory of Edith Rosenwald Stern, 80.188.

While the exact date of the Lunar New Year changes, it generally coincides with the arrival of the first plum blossoms in Japan. During the season, manzai dancers, such as the ones shown above in a work by Nakamura Hochu, would go from house to house, singing and playing instruments, like the small drum carried by the figure on the right.

The inscription at the top of the painting reads:

Born with

Liveliness and merriment

Blossoms of the plum

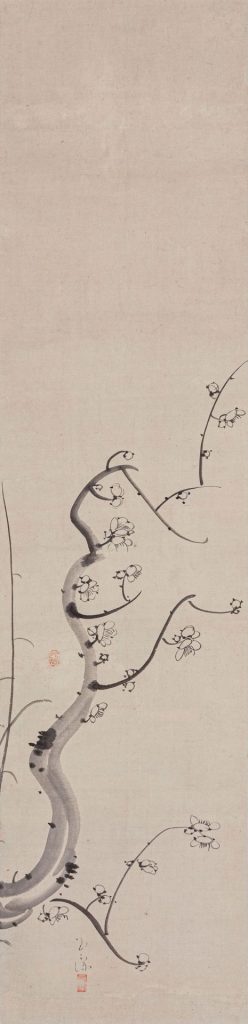

Ike Gyokuran (1728-1784), Plum Blossoms. Ink on paper. Gift of Kurt A. Gitter M.D. and Alice Rae Yelen, 97.849.

The symbol of the plum can also be seen in this delicate ink painting by Ike Gyokuran, one of the pre-eminent female artists of the 18th century. The daughter and granddaughter of independent women, who were entrepreneurs and poets—Gyokuran began her study of poetry as a child.

Sakai Doitsu (Japanese, 1845–1913), Three Friends of Winter. Ink and color on silk. Museum purchase, Muriel Haspel Fund, 99.266.

The blossoming plum signifies the end of winter. In the painting above, Sakai Doitsu, a late 19th-century artist, depicts a classic theme, the “three friends of winter.” These hardy plants survive the harshness of winter and set forth new growth in the spring, becoming traditional symbols for resilience, rebirth, and long life.

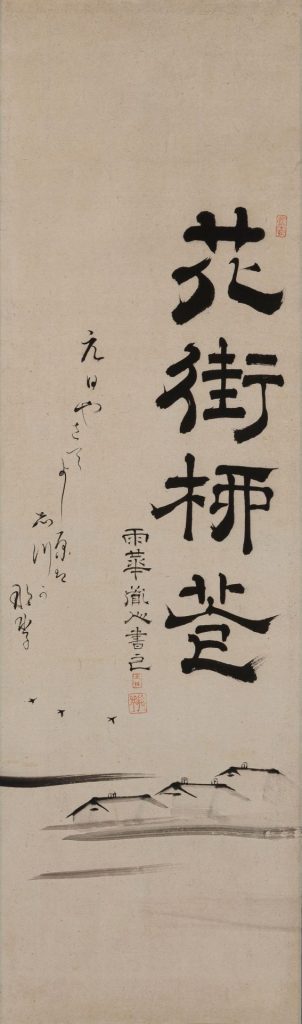

Sakai Hoitsu (Japanese, 1761–1828), Flower and Willow World. Ink on light color paper. Gift of Kurt A. Gitter, M.D., and Milie H. Gitter, 83.5.

And finally, a quieter scene from New Year’s Day.

The “Flower and Willow World” of this painting’s title refers to the “licensed quarters” or district outside of Edo—now Tokyo—known as the Yoshiwara, where courtesans, sex workers, and entertainers lived and conducted business. The poem to the left of the title reads:

New Year’s Day–

And now the Yoshiwara

Is quiet

New Year’s Day was the only day of the year where men were absolutely required to be at home with their families. Consequently the Yoshiwara, with its brothels, tea houses, theaters, and other venues for men’s entertainment, was uncharacteristically silent. This scroll is the first of a series of twelve, representing the months of the year in the Yoshiwara.

Happy Year of the Tiger from NOMA!