Born on a cotton farm in rural Mississippi in 1946, McArthur Binion is now one of the most vital and important voices in contemporary American art. To create his iconic paintings, Binion collages highly personal markers of his identity—his birth certificate, identity cards, family photographs and address books—into seemingly impersonal grids of oil stick, ink and graphite. His paintings offer a powerful meditation on the persistence of history and memory, revealing how personal meaning can emerge out of even the starkest and most minimal forms. Binion is among 120 artists who will be participating in the prestigious 57th Venice Biennale from May 13 – October 26, 2017.

On March 10, NOMA will unveil a newly acquired painting by Binion, which will be unveiled to the public on Friday, March 10, alongside a group of new acquisitions of works by contemporary African American artists that honor the life and legacy of New Orleans chef and civil rights activist Leah Chase. The exhibition, NEW at NOMA: Recent Acquisitions in Modern and Contemporary Art, will remain on view through October 1, 2017. That same evening, Binion will present a lecture on his life and work at 7 p.m. that evening. NOMA’s Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Katie A. Pfohl talked to Binion in advance of his March exhibition and lecture, and Arts Quarterly offers an edited transcript of that conversation here.

McArthur Binion was born in Macon, Mississippi, in 1946. In 1973 he became the first African American to graduate from the prestigious Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. He currently resides in Chicago.

You were born in a small town in rural Mississippi. How did you decide to move to New York and become an artist?

My head does not come from art history—I am a true rural modernist. The first time I ever saw a painting was when I was 19 years old. I was working for a new magazine up in Harlem—basically as a sophisticated delivery guy—and the editor sent me to deliver a package to the director of the Museum of Modern Art. I was waiting by the coat check, turned around, and saw a painting by Wilfredo Lam—although I did not know who that was, yet. It was really a hugely emotional experience for me. I had read about painting in literature, but I had never seen one, or realized that painting could be of philosophical nature, that it could truly make you feel and think. After that, I decided to become a visual artist but the whole thing was so totally foreign to me—and I was totally no good at it! So I buckled down and drew for forty hours a week for two years straight, and finally I got it. I already had my head, but I had to find my hands.

In the 1970s, New York was divided between abstract artists like Sol LeWitt making abstract, minimalist work and and artists interested in exploring identity and politics who wanted to make questions of race, gender and sexuality more fully part of the conversation. Given all that was happening politically at the time, why did you choose to create abstract paintings?

First of all, it was not a conversation between these artists. It was an opposition. For me, the most challenging thing I could do was work to find some humanity within abstraction. The goal, for me, was to make abstraction personal. When I started working, it had never been done that way. I wanted to smash all those guys like Sol Lewitt. I’m always challenging different painters in my studio—I will smash Cy Twombly one day, just crack him in half, and then I’ll take Jasper Johns and smash him too. With those guys, it was always something heady, and for me smart is absolutely boring. I want to swing with my emotional content, that’s what I am after. For me, the most genuine experience is to look at a painting and have no expression—no language for it—but to cry.

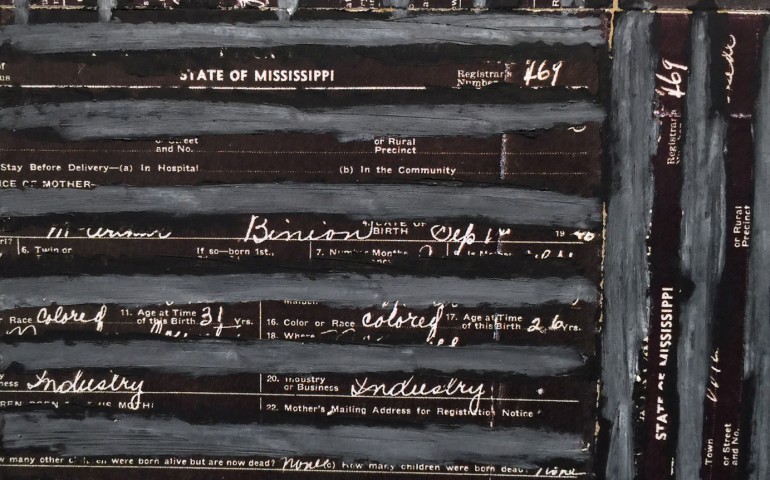

In your DNA: Black Painting series, one of which NOMA just acquired, you underscore your Southern roots by collaging your birth certificate—which reads Macon, Mississippi—into your paintings. Do you consider yourself a Southern artist?

It was very scary for me to start using my birth certificate in my paintings. Have you seen the picture of my birth house in Mississippi? You see this house, you see my whole story. Do you know that I am one of eleven children, nine of which were born in that two-room house? The South is where all the original black outsiders came from, and I was born in the real South. My brain just has that imprint, and it is still a part of me. One day I was painting, and I just kept coming back to that birth certificate, how under race it said colored, but because my birth certificate was a copy, colored was written in white on black. My next series of paintings, half are going to have my birth certificate, and half are going to have a photograph of a lynched man, but you are going to have to look really hard to see it under the paint. This is not about race, this is about history and images, about saying more with a lot less.