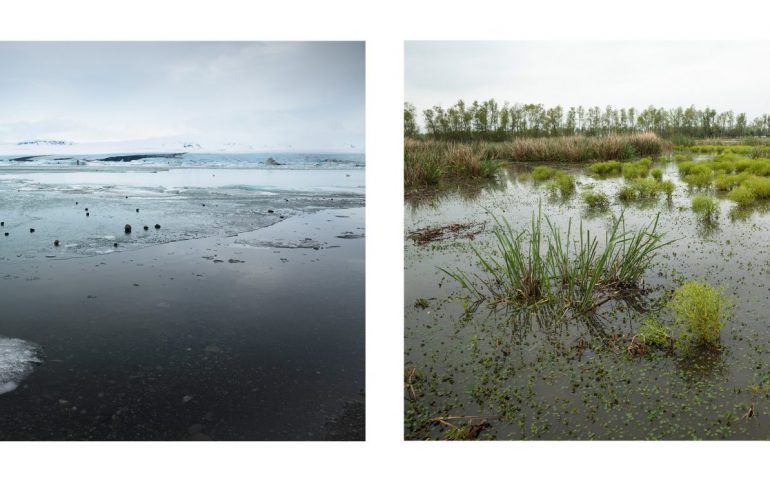

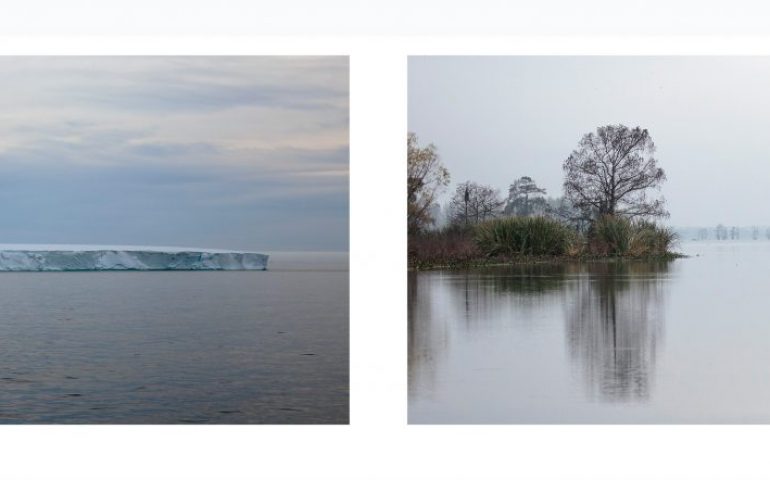

Over the past seven years, Tina Freeman has photographed the wetlands of Louisiana and the glacial landscapes of the Arctic and Antarctica. In Lamentations, on view through March 18, 2020, Freeman pairs images from each place in a series of diptychs that function as visual stories about climate change, ecological balance, and the relationship of natural phenomena across time and space. Images are paired aesthetically and practically, demonstrating how the rising waters along the coast of Louisiana are both visually and physically connected to the melting glaciers at the poles, despite the separation of vast distances. The large, color photographs in Lamentations make evident the crucial global dialogue about water in two physical states.

It is a simple construct: two pictures, side by side, each informing the other in a broad sweeping narrative about melting ice caps and rising sea levels. But Lamentations is anything but simple: it addresses the central issues of our time and does so in a form that wrestles with its own limitations. Put another way, this project profoundly engages with both its message and its messenger, with both the precarious existence of glaciers and wetlands and with photography itself. The diptych structure in Lamentations introduces a series of urgent narratives in a way that a sequence of individual photographs could not.

The meaning of any particular photograph is often incredibly slippery, subject to a variety of interpretations. Throughout history photographs have been used, by opposing parties, to argue both sides of the same story. The challenge for any photographer, especially one with a specific story to tell, is to somehow direct the viewer toward his or her way of seeing the image, to control the narrative. In magazines and newspapers this is done, often inelegantly, with captions—text that necessarily explains what a picture is about and why it is there. Freeman accomplishes it without text, using pictures alone to tell their own story. In each pair of images, one from the Arctic or Antarctic and its companion from Louisiana, the meaning of each individual image is framed and provoked by the other. A fallen tree in a swamp echoes the contours of a musk ox skeleton on the tundra, for example, with both becoming specters of loss. Each work becomes a declarative sentence, almost shouting that we cannot possibly understand this without that. When we begin to understand that this is the life-threatening loss of coastal refuge, and that is the increasingly fast dissolution of glacial ice, the global stakes truly come into focus.

The images are beautiful, but the beauty of each picture is quickly and constantly qualified by the presence of its partner. The wild irises of the Louisiana wetlands may seduce us for a moment, but that elation is quickly tempered by the adjacent threat to their existence. In this sense, each image is persistently haunted by its neighbor, with some pairings emphasizing the beauty that might be lost and others emphasizing the balance between disparate areas. In one diptych, for example, melting mounds of ice face off with a parade of cypress tree knees, but the quick realization that the first is shrinking while the other is growing underscores a fragile balance, and the fact that melting ice and sea-level rise is a zero-sum equation.

Each pair also effectively erases the vast distances that physically separate the subjects, forcing us to confront, in a single viewing, subjects that are directly connected but not normally apprehended together. This often results in unexpected relationships. Without this work, for example, who would have considered that in both Louisiana and the Arctic, the dead cannot be truly buried, as both lack permeable and stable ground in which to do so? This is a story about life and death, and how thin the line between them actually is. The title, therefore, is almost prophetic, suggesting a world in which that line has been irrevocably crossed. Lamentations carries with it associations of mourning, of weeping—a powerful metaphor for the melting of ice—and of what happens in the wake of profound loss.

Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs