The works of art contained in NOMA’s galleries and the Besthoff Sculpture Garden depict the full gamut of human emotions — from love and compassion to vengeance and fright! This Halloween, prowl our halls and the shadowy outdoor paths to view scenes and objects that are guaranteed to give visitors the willies. From snakes, spiders, bats, toads and skeletons, to depictions of murder and an unwelcome visit from the grim reaper, you never know what might be lurking around the next turn. Presented here are ten selections from the permanent collection and loans.

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1996, Bronze, ed. 5/6, Museum purchase, Sydney and Walda Besthoff Foundation Fund, 98.112

Anyone with arachnophobia will certainly shiver at the sight of the giant bronze Spider in the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden. The sci-fi movie-sized arachnid, standing more than ten-feet tall, haunts the garden with its sprawling eight legs positioned akimbo. The sculpture, weighing close to 1,800 pounds, thankfully does not include a web of scale size. Bourgeois’ preoccupation with spiders has spanned her career, starting in the 1940s but becoming more common in the 1990s. Her Spider sculptures are on display around the world. The artist’s inspiration is far from macabre, for as Bourgeois explains, “The spider—why the spider? Because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider.”

El Greco (Dominio Theotokopoulos) and Studio, St. Francis, c. 1570, Oil on canvas, Lent by the estate of William G. Helis

Dark and foreboding, with the exception of a solitary beam of light fighting off the surrounding darkness, the subject of El Greco’s dramatic painting, St. Francis, looks skyward and gestures at a human skull after receiving the stigmata. The dark tone of the painting and the elongated forms are not only typical of El Greco’s expressionistic style, but intone a sense of mortality to the work—the subject appears more akin to the skull near his skeletal fingers than to the vitality of the viewer. According to Catholic teachings, St. Francis’s hands and feet were divinely pierced in 1224 during a solitary period of fasting and prayer on Italy’s Mount Alvernia. His wounds bled for two years until he died in 1226. The Stigmata of St. Francis is observed very September 17th.

Otto Marseus van Schrieck, Serpents and Insects (detail), 1647, Oil on canvas, Gift of John J. Cunningham, 56.30

Dripping in creepy-crawlies, Serpents and Insects is practically a jump-scare of a painting, revealing a veritable witch’s brew of frightful creatures some of which only gradually come into view. With mouths agape, the serpents in the painting writhe around the foreground among mushrooms and moths. A toad devours a white-winged meal—perhaps before this unsuspecting amphibian too becomes dinner? Many of Schreik’s paintings feature nightmarish fauna that dwell on the damp forest floor: insects, frogs, lizards, and snakes. The Dutch Golden Age artist raised snakes in a vivarium behind his home. After multiple modeling sessions with his reptilian pets, these snakes became so tamed they would remain in whatever position in which he posed them. Focusing on the brevity of life, Serpents and Insects is a reminder of what may be lurking just underfoot.

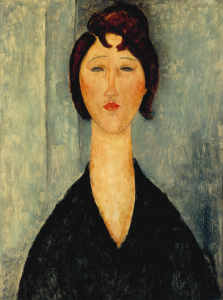

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of a Young Woman, 1918, Oil on canvas, Gift of Marjorie Fry Davis and Walter Davis, Jr. through the Davis Family Fund, 92.68

For those with automatonophobia, or fear of humanoid figures, Amadeo Modigliani’s haunting portrait of a young woman may give you the chills. In his signature Expressionist style, Modigliani’s Portrait of a Young Woman features a solemn female figure with an elongated neck dressed in black—with deep, charcoal-colored eyes devoid of expression. The subject is clearly a young woman, but her blank eyes neglect the emotion usually found in portraits.

Giovanni Martinelli, Death Comes to the Banquet Table (detail), c. 1630-1640, Oil on canvas, Gift of Mrs. William G. Helis, Sr., in memory of her husband, 56.57

A skeleton rudely interrupts a 17th-century dinner party in Giovanni Martinelli’s Death Comes to the Banquet Table. This ghastly specter of death itself, with a nearly-empty hourglass held in its bony hands, startles guests who look on in horror. Spooky and surreal, the bone-jarring intruder shows just how aware the artist was of cruel fate in his day and age. Plagues periodically swept through Europe, infant mortality rate was high, and medical practices were primitive at best. Martinelli would have been no stranger to death and its brutal timing.

Veracruz Culture, Mexico, Gulf Coast, Palma Depicting a Ball Player and Flying Bats (detail), c. 200–900, Volcanic stone, On loan from the collection of Hugh Allison Smith

Bat mythology is extensive among the Native American cultures of Mexico and Central America, where the winged rodents are symbols of death and the underworld, sorcery, darkness, and sacrificial rites. In some Mexican tribes, bats are believed to carry messages to and from the spirits of the dead. In others, bats are believed to cause the sun to set, bringing on the night. In the volcanic rock carving Palma Depicting a Ball Player and Flying Bats, bats fly around a ball player, perhaps one destined for human sacrifice. These Mesoamerican sporting events were rigged so that captives were put to death following games that mimicked cosmic forces, rituals performed to appease the gods. A palma is a stone representation of a palm frond that was used as ceremonial clothing by ball players.

Probably Swiss or German, “Rusticated” Framed Mirror (detail), c. 1875, Painted and parcel-gilt carved wood, with some composite materials, mirrored glass, Museum purchase, William McDonald Boles and Eva Boles Fund, 2016.53

A dead rabbit hangs from a cluster of grapes in this “Rusticated” Framed Mirror on display in NOMA’s Lupin Foundation Center for Decorative Arts. Two lifeless birds also dangle on either side of the reflective glass, typical hunting-trophy ornaments on “rusticated” furniture that became popular in the Victorian Age. This style is also known as “Black Forest,” in reference to the manufacture of such carved furniture in the area around Brienz, Switzerland. The Black Forest, or “Schwarzwald,” is known as the home for sorcerers, wizards, witches, and dwarves in Germanic folklore.

India, Nagaland, Basket with Monkey Skulls, 19th century, Palm frond, raffia, and monkey skulls, Gift of Siddharth K. Bansali, 98.314

The Naga people inhabit far northeastern India in a region bordering Burma/Myanmar. For generations a masculine rite of passage required headhunting among warring tribes, a practice that was forbidden under British colonial rule in the 19th century. As a substitute for human skulls, the craniums of monkeys were used to decorate this basket. “A Naga village could not remain even ideally at peace as long as there prevailed the belief that the occasional capture of a human head was essential for maintaining the fertility of the crops and the wellbeing of the community,” wrote Fürer-Haimendorf, a German anthropologist who studied the Naga culture nearly a century ago.

Alexandre-Marie Colin, Othello and Desdemona, 1829, Oil on canvas, Museum purchase, The Bert Piso Fund, 2001.329

The murderous climax of William Shakespeare’s drama Othello is depicted in this painting by French artist Alexandre-Marie Colin. The play, believed to have been written in 1603, centers upon two central characters: Othello, a Moorish general in the Venetian army, and his unfaithful ensign, Iago. Othello is seen here fleeing a a crime of passion after he strangles his wife, Desdemona, upon believing she is a serial adulteress. He later learns he has been tricked into believing that Desdemona was unfaithful from rumors planted by Iago. This causes Othello to stab Iago and commit suicide. Othello and Desdemona is on view in the exhibition Orientalism: Taking and Making, which examines racially insensitive Western interpretations of the Middle East, North Africa, and East Asia. Desdemona was a bold fictional character for her time, defying family expectations and social convention by engaging in an interracial marriage.

George Segal, Three Figures and Four Benches, 1979, Painted bronze, Gift of Sydney and Walda Besthoff, 98.147 (Installation by Mrs. P. Roussel Norman)

George Segal’s Three Figures and Four Benches take on an melancholic, ghostlike quality in the Besthoff Sculpture Garden, particularly when floodlit during nighttime events. Among the most well-known names in the Pop Art movement of the mid-twentieth century, Segal would essentially mummify his subjects in plaster casts to create lifelike figures from the hardened material. Initially, Segal kept his sculptures stark white, but a few years later he began painting them, usually in bright monochrome colors. Eventually he started having the final forms cast in bronze, including this sculpture, and sometimes patinated white to resemble the original plaster.

The New Orleans Museum of Art will be open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Tuesday, October 31.

David Johnson, editor of museum publications, and Katelyn Fecteau, editorial intern, contributed to this list.