In early 2024, Kurt Gitter and Alice Yelen Gitter gifted over fifty works of Japanese art to NOMA. This remarkable donation includes major works by Edo-period painters (1615-1868), as well as significant works of ceramic art from the late 20th century to the present day. This exhibition, the first in a series, celebrates these gifts and honors more than five decades of philanthropy by the Gitters, who have donated nearly 250 works to NOMA, helping to establish and develop the museum’s Japanese art collection.

The present exhibition pays homage to the 1976 show Zenga and Nanga: Paintings by Japanese Monks and Scholars. This was the first NOMA exhibition to highlight the Gitters’ collection, and after its premiere in New Orleans, the presentation traveled to five other museums in the United States. Both exhibitions focus on paintings by Zen and literati artists, two of the primary artistic currents of the Edo period.

Among the painting traditions to flourish during the Edo period, the Nanga, or literati, style was among the most significant. Fueled by the new Tokugawa Shogunate’s embrace of Confucianism, Japanese artists studied Chinese Ming and Qing Chinese painting subjects and styles (largely through reproductions in woodblock-print painting manuals), as well as embraced the values of a Chinese gentleman scholar. While largely professional painters, unlike their Chinese counterparts, Japanese Nanga artists were musicians, poets, historians, calligraphers, art historians, and more. Their rich cultural knowledge and practice simultaneously infused their paintings with a deep reverence for tradition, and reflected their engagement with the present.

Zen painting underwent a significant revival in the Edo period, due in part to the increasing importance of the tea ceremony. Using only black ink and paper, Zen monks communicated spiritual truths and guidance to their followers. The fall of the Chinese Ming government in 1644 led to a number of monks emigrating to Japan, where they came to be known as the Obaku sect. These monks exerted great influence on painters of all traditions, bringing with them contemporary works of Chinese art and practicing a distinctive style of calligraphy. The most important reviver of Zen painting was Hakuin Ekaku, who broadened its scope and audience, inventing new subjects and themes, an approach perpetuated by generations of followers.

There were direct connections between these seemingly distinct approaches to art and communities of artists. Literati painters, such as Ike Taiga studied Zen with both Hakuin and the Obaku monks. The Zen monk Gocho Kankai wrote inscriptions on paintings by both literati artists and his fellow Zen monks. Envisioning Japan draws together recent and prior donations from the Gitters, gifts they facilitated, and museum acquisitions, to illuminate the distinct, yet interrelated strands of this remarkably diverse period of artistic production.

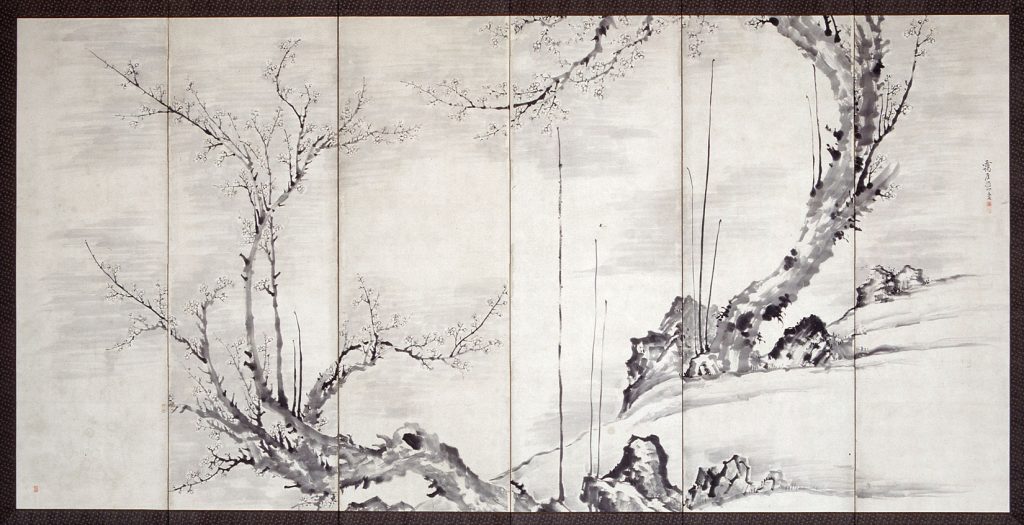

Bamboo and Plum Blossoms (Right)

n.d.

Takaku Aigai

Ink and color on paper

Bamboo and Plum Blossoms (Left)

n.d.

Takaku Aigai

Ink and color on paper

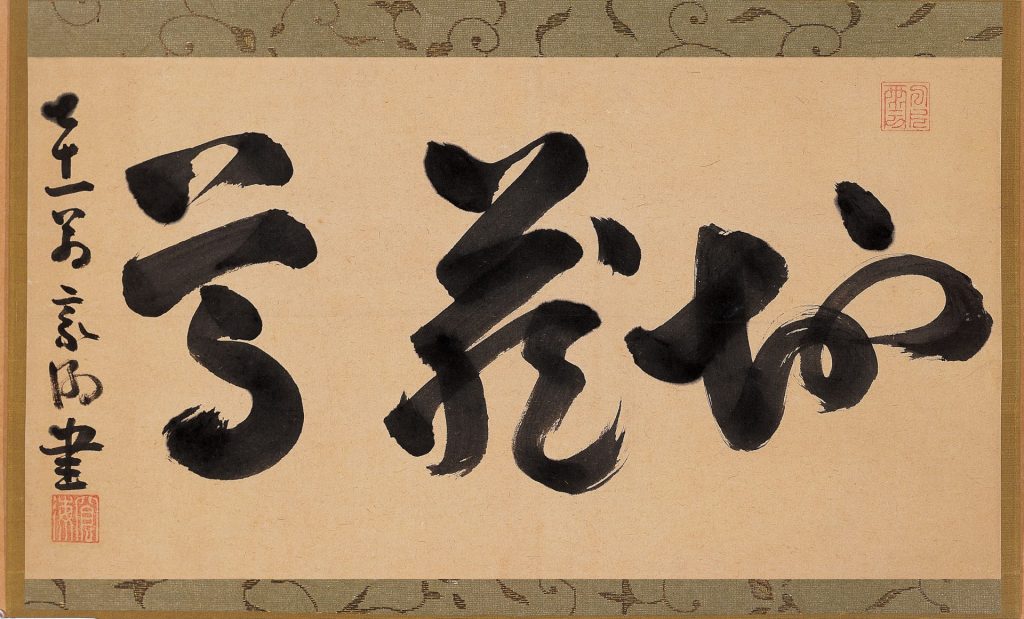

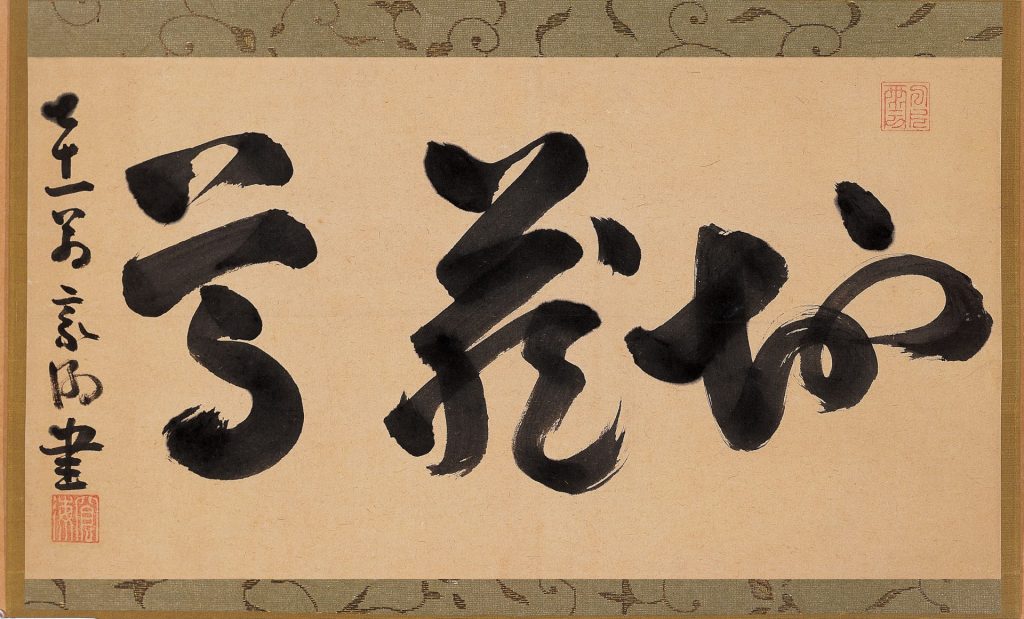

Respect Jizo

1809

Gocho Kankai

Ink on paper

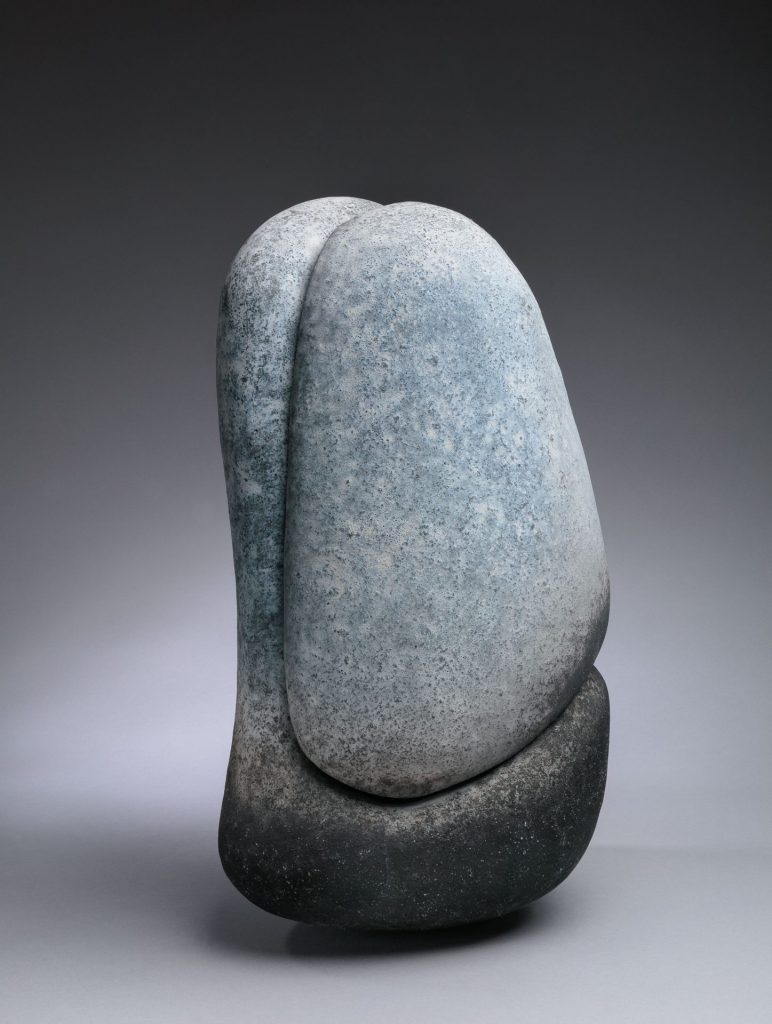

Saiki Sculptural Form

n.d.

Gomi Kenji

Stoneware with ash glaze