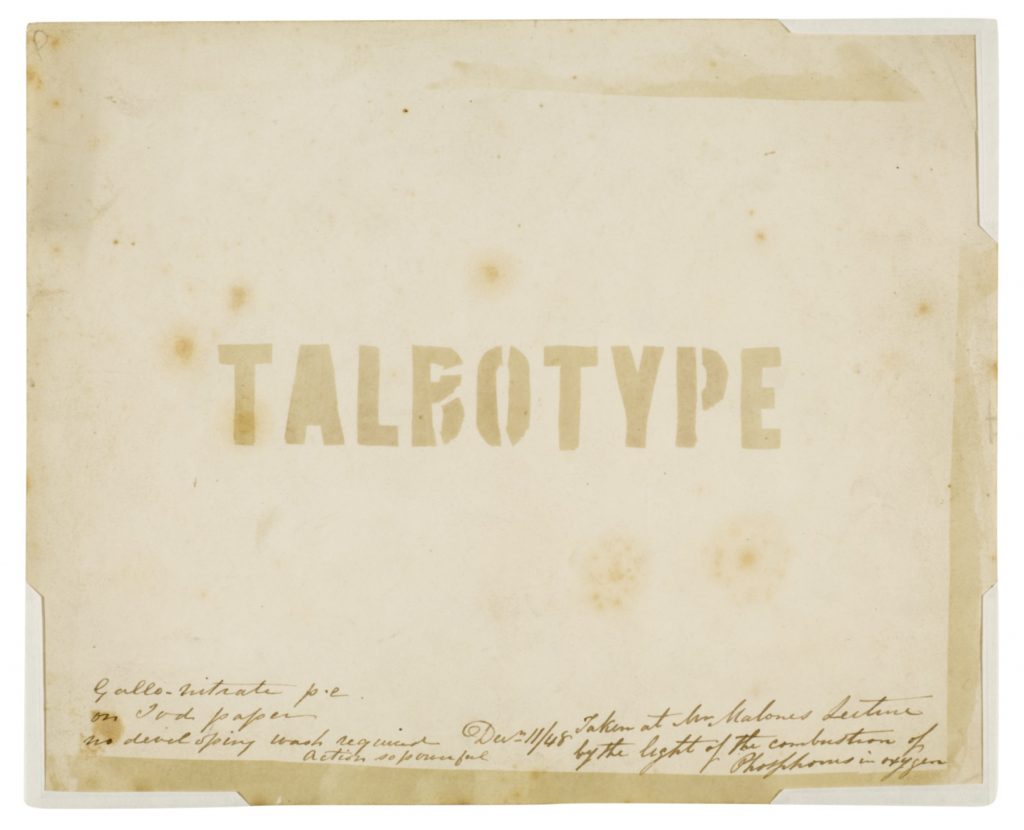

Thomas Augustine Malone (British, 1823–1867) Demonstration of the Talbotype, 1848, Calotype (Talbotype) paper negative, 7 3/8 x 9 1/8 in. (18.8 x 23.2 cm), Museum purchase, 2012.90

The word “photograph” encompasses a wide variety of processes, practices, materials, and objects. Today, it is used to describe images on paper, glass, or metal, as well as digital images that have no permanent physical support. As a term, it has become so commonplace that it is easy to forget that there was a time when the naming of photography was a matter of intense debate and the word “photography” was but one of many under consideration. For several decades before and after the introduction of photography to the public in 1839, inventors, critics, theorists, and scientists came up with a range of terms to describe the myriad of processes that make up photography’s origins. One such process—a method of capturing images on chemically sensitized paper—was created by British scientist and inventor William Henry Fox Talbot. He presented some examples in London shortly after Frenchman Louis Daguerre’s invention of the daguerreotype—a chemical image on a metal plate—had been announced in Paris. Talbot resisted the urging of his friends, who felt that his process could and should serve as a counterpoint to Daguerre’s self-referential method, and ultimately favored elegance over vanity, choosing the term “calotype” (from the Greek “kalos,” meaning beautiful, and “type,” meaning image.) His most ardent supporters, however, honorifically referred to the process as “Talbotype.” This term, therefore, functions as a synonym for early paper photography—but one freighted with personal and even nationalist sympathies.

Thomas Augustine Malone had learned this process directly from the inventor, and throughout the early to mid-1840s he worked closely with Talbot and his chief assistant, Nicholaas Henneman, to establish a photographic printing firm. On December 11, 1848, Malone stood before an audience at the Western Literary and Scientific Institution in London’s Leicester Square to demonstrate the effects of light on chemically treated paper. Malone covered a piece of prepared paper with a stencil, closed the windows in the lecture hall, and then ignited a fuse of phosphorous, resulting in a brilliant and sustained light in the darkened hall. After several seconds (or perhaps minutes), the phosphorous was burned up and Malone removed the stencil. There, graphically represented on the paper in block letters, was the word “Talbotype.”[1] Information about this demonstration was recorded in ink on the photographic record itself. Rarely does an object have so much of its own history inscribed on it.

Malone’s demonstration piece, believed to be one of a kind, then, is a strange but wonderfully conceptual work from early photography. As a photograph that consists of nothing but the word “Talbotype,” this work gives us photography twice over—that is, in word and in image. Photographic images alone can be powerful and emotionally evocative things, but they are also often open-ended and ambiguous, and subject to a multitude of interpretations. Malone’s work preemptively circumvents this uncertainty by combining both word and image in an endless circle of reference: the word is the image and the image is the word.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

[1] For more on Malone’s lecture, see Larry J. Schaaf, Sun Pictures, catalogue 21, Talbot’s World: A Gallery of Natural Magic (New York: Hans P. Kraus Jr., 2012), 34.NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. Your gift will make a direct and immediate impact as NOMA welcomes our community back to the museum and sculpture garden, plans new exhibitions, and develops virtual and at-home arts education resources for school partners.