None of the following photographs were taken by photographers in their own homes. Rather, to make each of the images discussed here, a photographer had to gain permission to cross the threshold into someone else’s home. If that transaction calls to mind mythic negotiations that, supposedly, allow a vampire to enter one’s home (May I come in?), perhaps that anxiety stems from the very idea of a stranger turning a camera towards our most private spaces. Ideally, our homes are spaces that we craft to reflect our identities, bring comfort, and nurture relationships. In reality, home can also be stifling, lonely, or dangerous. Allowing an outsider to make a photograph that reflects any of these qualities requires vulnerability on the part of the subject, and trust placed in the photographer. Given a level of access, the photographer then makes choices about how they might convey the singularity of the home-space in front of them, and whether to expand or explode the domestic myths they have been invited to turn into a picture.

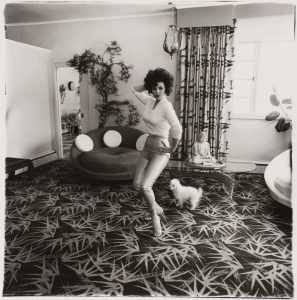

Diane Arbus (American, 1923-1971), Blaze Starr in Her Living Room, Baltimore, MD, 1964, printed later , Gelatin silver print , Gift of Katia and Howard Read, 95.570

When Diane Arbus went to Baltimore for an Esquire magazine profile on Blaze Starr, the burlesque performer had already achieved national fame, in part because of her affair with Louisiana Governor Earl Long. In another portrait from that same visit, Arbus photographed Starr in her work costume, which is to say, nearly entirely nude. Whereas a burlesque dancer might not be readily associated with a domestic identity, Arbus had Starr strike nearly the same seductive pose in her brightened living room. Fully clothed but in front of her stylish furniture, small dog, and a bonsai-style tree echoing Starr’s form, it remains debatable which of these two pictures is more revealing of Starr as a person. Although Arbus began her photography career in fashion, some of her most important work consisted of probing portraits taken in settings where the subject often found themselves—whether a park, workplace, or their home. As Curator Russell Lord points out in the article linked above, Arbus was highly cognizant of all of the players in the photographic event, including maker, sitter, and the camera itself. Whether or not we might judge Starr to be wearing a slightly softer facial-expression in her living room than behind the Two-O’Clock Club, Arbus uses both of these settings—work, home—as a way to present a fuller idea of Blaze Starr’s everyday life.

James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983), Family House, 1938, Gelatin silver print , Museum Purchase, City of New Orleans Capital Funds and P. Roussel Norman Fund, 76.43

In many of the portraits James Van Der Zee made at his studio he strove to create the illusion that his subjects were in finely decorated domestic spaces, using conventional props like columns, furniture, and flowers, but also realistically painted backdrops and special effects added in the darkroom. The photograph Family House, is an example of Van Der Zee’s less common practice of photographing people in their homes, and provides an example of where Van Der Zee found inspiration for the atmosphere he sought to emulate in his studio.

In this photograph, the patterns on the carpet, drapes, and other textiles in this bedroom appear so busy that it becomes easy to miss the woman lying under a blanket on the chair in the rear corner. In other photographs taken at the same time, Van Der Zee identifies this woman as “The Heiress,” and notes that she was bequeathed the residence when her long-time employers (who owned it) passed away.

Little more is known about the woman, but in this photograph and others, Van Der Zee portrays her as dwarfed under tall ceilings in rooms full of large furniture, mirrors, and art. Taken towards the end of the Great Depression, Van Der Zee’s “Heiress” series is often looked to as the artist’s attempt to model an emergent black middle class in Harlem, but we might also read this photograph as reflecting the woman’s ambivalence about her new property: having labored so long within the walls, she now appears overwhelmed by its size.

Lou Stoumen (American, 1917-1991), American Family, Camden, New Jersey, 1945, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, Zemurray Foundation Fund, 76.453

It is unclear how Lou Stoumen came to be in the home of the Pennsylvania family he photographed on the day that Franklin D. Roosevelt died. Stoumen volunteered for the Army in 1942 and worked as a photojournalist for Yank, a weekly magazine put out by the US military. Whatever Stoumen’s acquaintance with this family, their facial expressions indicate his visit was a somber one.

The first few letters of the President’s name are just visible on the newsletter in the father’s lap. The members of the family dominate the frame, but Stoumen includes a few objects that hint at how connected they might have felt to FDR and the ongoing war effort. A portrait in uniform underline the father’s own service (or a brother’s?) and the radio cabinet on the left likely transmitted several of the president’s famous fireside chats as he guided the country through the crisis of the Great Depression. Beyond these elements, and some markers of middle-class comfort or stereotypes, it becomes difficult to definitively surmise much else about this family or their home. In that sense, this photograph exhibits the limits of a single photograph to fully describe a family’s home. It might even be said, that the other photographs included in the picture—a military portrait, a formal event, two siblings on a cold day—are the only way we can grasp more about the family and a home that continually changes and evolves.

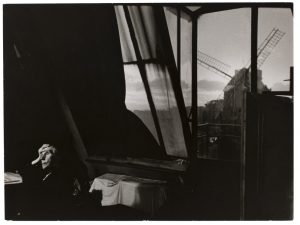

Bruce Davidson (American, born 1933), Mme. Fauché, the Widow of an Impressionist Painter, 1956, Gelatin silver print, Gift of Viron Kersh, 78.165

While Bruce Davidson spent his Army service in Paris in 1956 he befriended the 92-year-old widow of impressionist painter Leon Fauché. Fascinated with her routine movements in and around her home in Montmartre, Davidson spent a great deal of time with Mme. Fauché learning about her habits and allowing her to become comfortable in the presence of his camera. In this photograph, the widow’s open window frames one the iconic windmills in her neighborhood—a nod towards her link with a bygone-era in Paris when she and her husband rubbed elbows with artists like Henri de Tolouse-Latrec.

Davidson throws light on his subject and the cloth-draped furniture behind her, which only serves to increase the weight of the gathering dark in the apartment that evening. In contrast to Stoumen’s single moment, Davidson’s photograph pulls a stronger line through time, and can remind us that as we grow older our homes can fit and feel very differently. Davidson published his “Widow of Montmartre” series in Esquire magazine and showed them to Henri Cartier-Bresson, who subsequently invited Davidson to join the Magnum group.

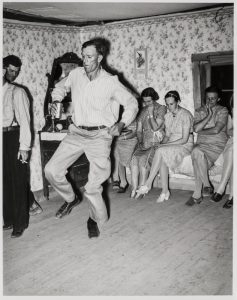

Russell Lee, (American, 1903-1986), Square Dancing at Home, Pie Town, New Mexico, 1940, Gelatin silver print, Museum purchase, Division of the Arts Grant Matching Fund for State Traveling Exhibitions Program, 79.316

In the final photograph featured here, Russell Lee captures a moment of levity during the Great Depression, and suggests how important our homes will be for friends and family when we can again gather safely after the Covid-19 pandemic. Lee took his first photographs about 1935, but just five years later he was employed by the Farm Security Administration to document the effects of the economic downturn in the Midwest and West. He drove to Pie Town, New Mexico, a municipality on the Continental Divide that (believe it or not) exists primarily because of and in order to sell pies.

Pie Town was populated my homesteaders and Dust Bowl refugees working hard to scratch out a living in the arid climate. Russell also photographed residents at work and play, including this square dance in someone’s home. With the furniture pushed to the walls, we can see this is domestic space being repurposed. The man with a drink in his hand has the floor and Lee freezes him mid-jig. The forced perspective of the camera makes the man seem impossibly large and as if he might leap through the ceiling. Perhaps, rather, the ceiling was actually impossibly low, but Lee’s tightly composed photograph collects the social energy in this home, where petít-farmers and pastry cooks have eagerly dressed up to pass a Saturday evening in one another’s company, and in a friend’s lovely home.

—Brian Piper, Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Photography

Virtual programs at NOMA are made possible in part by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.

▶ DONATE NOW