All photographs depend on different combinations of chemicals and minerals to turn light into pictures. This week, as NOMA focuses on the materials and processes that artists use to create, we’d like to give some special attention to a unique and beautiful variety of photograph: the platinum print. It may come as no surprise that a photography curator finds it difficult to choose a favorite photographic process, but platinum printing ranks high on my list and NOMA’s collection boasts a number of these fantastic objects. Considering just a few of them together gives us a chance to appreciate the variety of ways that photographers have used platinum to great effect.

Throughout the history of black and white photography, silver has been the most widely used element, valued for its sensitivity and availability. While many early photographers and scientists experimented with platinum (and its close variant, palladium), William Willis first took out a patent for the platinotype in 1873. By the 1880s platinum printing paper had been made commercially available. Whereas light-sensitive silver was to be suspended on top of photographic paper (at that point in time using either a salt-solution or egg whites, later in a kind of gelatin) platinum affixes directly to the surface of the paper. As a result, all platinum prints have a matte finish which contributes to their velvety, rich appearance. Compared to silver, photo-sensitized platinum is heavier, slower to react when exposed to light, and (you guessed it) more expensive. While platinum prints are more stable than silver prints, their slow printing speed means that they must all be contact printed, with the negative right on top of the photo-paper. The extra effort and cost effectively served as a barrier to platinum prints for many photographers. For those willing to face those difficulties the reward is a photograph with an incredible range of lush grey mid-tones that cannot be achieved in silver prints, while also registering tones that range from pink to reddish-brown.

Peter Henry Emerson (British, born Cuba, 1856-1936), Towing the Reed, 1886 , Platinum print, Museum purchase, Jung Enterprises and WVC Funds, 75.3

Peter Henry Emerson was among the first photographers to embrace platinum printing, and to do so in a way that utilized the full potential of the method. Emerson was an early advocate for photography as a fine art, on the principle that a photograph could perfectly describe nature. He rejected artificially constructed and posed images, and focused primarily on the people and environs of the rural region of East Anglia. Emerson was also a physician, and strove for his photographs to emulate natural human vision. Here, the platinum print enhances the soft edges in the background of the photograph, out of focus the same way the farther-away farmer would be to our eyes if we were standing by the creek, looking at the man pulling the boat. This photograph differs from many platinum prints, which can be printed very dark as shown below, because Emerson printed it in way that enhances the bright sunlight casting shadows behind his subjects. Later in his life, Emerson rejected the idea that photographs could be anything more than mere documents, which seems a shame because Towing the Reed remains a true masterwork.

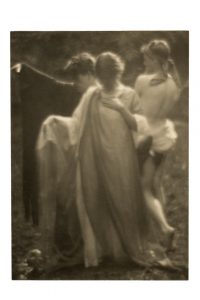

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883-1976), Decorative Panel, 1912, Platinum print, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. P. Roussel Norman, 74.284

Imogen Cunningham began her photography career in the company of several important pictorialist photographers, determined to give photography the status of fine art. Trained as a chemist, Cunningham learned the platinum process while working for Edward S. Curtis in 1907. Over the next several years she perfected her technique, and learned to make her own platinum paper that would enhance brown and sepia tones in her work. This photograph, Decorative Panel, bears some of the markers traditionally associated with the pictorialist school: soft focus, classical themes, and laborious printing methods. The gradual tones made possible by the platinum process coupled with the extremely soft lines of her subject’s cloaks give Cunningham’s work a warm, ethereal, and even dreamlike impression. Cunningham made this photograph early in her career, and it stands out against her later work with the f/64 group in California when she made precise formal studies of flowers.

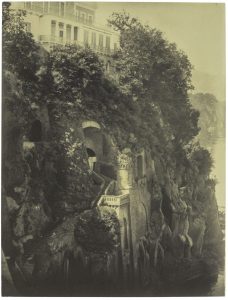

Karl Struss (American, 1886-1981), Capri, 1912, Platinum print, Gift of Jim and Cherye Pierce, 2018.43

Another platinum print made in 1912, Capri, exemplifies another possibility for the platinum process: because they must be contact printed, the sharpest of negatives turn into prints with minimal loss of detail. Karl Struss was also associated with pictorialism, and this photo of the staircase under an Italian mansion clearly portrays the mortar between every stone. While the negative might have been retouched, this platinum print transmits an incredible amount of detail, primarily through contrast in features on the cliff-side. Beginning in the 1920s Struss applied his vision to the burgeoning motion picture industry, winning one of the first Academy Awards for Cinematography.

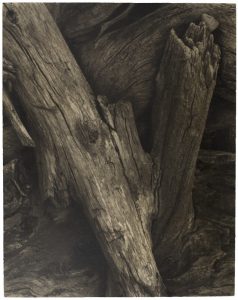

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976), Driftwood, Maine, 1928, Platinum print, Museum purchase through the National Endowment for the Arts Grant, 75.51

Paul Strand also moved between photography and motion pictures during his professional career. This photograph of driftwood in Maine showcases many of the qualities covered above—sharp detail in the whorls and grain of the wood, a rich, velvety surface, and subtle transitions in brownish tones that are perfect for an image of wood. Viewed alongside Emerson’s Towing the Reed, Driftwood seems very dark, and carries a real sense of weight (contrary to the general lightness of dried driftwood). Made prior to his Mexican period and full-time engagement in film-making, this work is one of Strand’s finest platinum prints, and a favorite in NOMA’s collection.

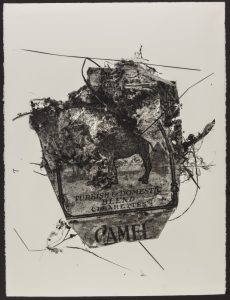

Irving Penn (American,1917-2009), Camel Pack, 1975, printed later, Platinum palladium print, Gift of the artist, 85.154.1

Use of platinum printing waned somewhat during the twentieth century, but artists devoted to use the method continued to produce rich results. Perhaps best known for his advertising and fashion photography, Irving Penn also made a number of striking modernist still-life photographs of found objects like this pack of Camel cigarettes, part of a series of objects rescued from a gutter. This photo depended on a combination of platinum and palladium, and to print them so large (about 30 x 22 inches) Penn devised a system to secure the paper to aluminum plates and print in stages. The contrast of the all-white background and precisely detailed decay of the package creates an even more stark, even bleak effect. With this photograph Penn shows us that that the platinum process can elevate even garbage to high art.

Lois Conner (American, b. 1951), Atchafalaya Swamp, Louisiana, 1988, Platinum print, Museum purchase, Funds provided by Cherye R. and James F. Pierce, 2014.76

Finally, this beautiful work by Lois Conner renders the Atchafalaya Swamp in haunting detail. Conner specializes in horizontal landscapes made with a panoramic or banquet camera, which holds a negative that is almost 7 x 17 inches. When viewed without overmatting in place (as in this image ) this photograph also provides some insight into the production of a platinum print. Because it must be contact printed, and the photographer is working in the dark, she applies the chemistry to the paper in a space bigger than the negative in order to guarantee that the negative could not be misaligned. When exposed to light then, the solution not covered by the negative turns a dark black—although we can see brush strokes. Within the frame, Conner’s process allows her to render the swamp in the darkest of greys, without losing any detail. Where Emerson’s photo above seems warm and bright Conner leans into the fog. The abandoned boat we can see increases the sense of tangled mystery until it is overwhelming. This photograph is a fantastic example of the full history of platinum printing, a legacy that Lois Conner continues to advance today.

—Brian Piper, Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Photographs

Many photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

NOMA is committed to uniting, inspiring, and engaging diverse communities and cultures through the arts — now more than ever. You can support NOMA’s staff during these uncertain times as they work hard to produce virtual content to keep our community connected, care for our permanent collection during the museum’s closure, and prepare to reopen our doors.