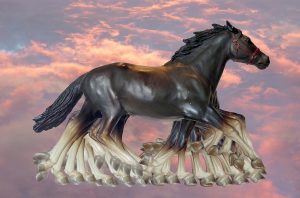

Lee Deigaard, Steady Star, 2011, Video, Promised Gift of Arthur Roger, EL.2016.132.22, © Lee Deigaard

Lee Deigaard is among the artists represented in Pride of Place: The Making of Contemporary Art in New Orleans, an exhibition of more than 70 works of art donated by renowned New Orleans gallerist Arthur Roger. Deigaard’s video, Steady Star, features a toy horse in motion against a sky that progresses from day to night palettes. The artist credits a childhood love of horses as inspiration for the piece. Many of her works reflect nature, particularly animals and their interaction with the environment. Arts Quarterly editorial intern Katelyn Fecteau spoke with Deigaard in advance of an Artist Perspective lecture at NOMA on Friday, July 28, at 6 p.m.

What is your general approach to your art?

My general approach is trying to be open to the incidental things that I discover with unusual angles of coming upon something. A lot of what I learn about the world happens through what animals show me. They have much more sensitive sensory perceptions. A lot of my imagery comes from that or from what animals do, or trying to pursue understanding of animals in the natural world.

Nature is a strong theme in your work. How so?

Yes. It’s essential I’d say. It’s working from life, in a way, but not in the way we’re used to talking about it. It’s living out in the world. When I walk my dog, I watch her align herself in the world with things. She uses her body—she’s carrying nothing, wearing nothing. I learn a lot about ways of thinking about drawing and space by watching her very subtle physical interactions with the environment.

What prompted you to create Steady Star?

I was one of those girls who loved horses. I suppose there’s two types of girls: those who think horses are everything and those that don’t understand the fuss. I grew up in a city and I couldn’t get near any horses really because to be near a horse is a privilege—in all senses of the word. It’s just a privilege being near them because they’re so special and so exquisitely sensitive and can read us better than we can read ourselves in many ways. So growing up, I read all the books about horses. I had some plastic horses like the model that’s in the installation—that was my childhood horse. My time with horses had to deal with the imagination: drawing them, thinking about them, and somehow, trying to be ready for the day somebody tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Little girl, we have a hundred horse stalls that need cleaning. You’re on. Do it.” I was prepared somehow.

The piece kind of arose out of how the gallantry, devotion, and steadfastness of horses can be overlooked—just like the strength of little girls. For me, as a child, the dream of a horse was a very enduring one. It had abstract elements to it. I grew up among relatives, great grandparents, who all had horses, so I grew up surrounded by pictures of family members with horses. I think I definitely started to think of horses as my kin, but I had to be an adult before I got to be around horses and know them personally.

This piece is about, in a dream, horses. It’s literally a projection of a horse, an imaginative projection. It’s also about a horse running and never growing tired. A lot of what we think of when we think about horses is about freedom. Dreaming of horses is about dreaming of freedom. The lives of most horses are the opposite. They don’t have a lot of autonomy or freedom. Animal lives are very short relative to how we’d like them to be. A horse that runs and never grows tired, is sort of a dream itself. Arthritis does not come for the horse. It’s about that.

The sound recording that you hear [with the video] is a recording of a horse sleeping. It’s immensely difficult to record the sounds of a sleeping horse. That’s a horse friendship where he trusts me and we nap together in the barn.

How did you meet Arthur Roger, and how would you say he inspired you in your art?

I got to know him because he would come into The Front, the gallery artist collective of which I’m a part. He would come in on Sundays and if I were gallery-sitting, I could see him then. He came with his dog. Of course, any artist in town knows him from his gallery and the artists he shares with us; it’s such a good gallery. That’s actually where he bought Steady Star, from one of those Sundays when he dropped by with his dog.

He gave me my first solo show in a commercial gallery in New Orleans. That was last year. He’s decisive, and things happen quickly—it’s very transformative. It’s wonderful to be benefiting from him as an artist.The show got put together and happened, and with such beautiful standards of presentation. Everything about working with him and his gallery was an absolute pleasure. He does wield a great deal of influence in changing the life of an artist. He’s built up such a well-deserved reputation. If he likes your work, you feel quite selected and special.

What do you hope to inspire with your art? What do you want people to feel?

If I look back at my whole career, I think I was pursuing ways to encourage empathy, in my case, particularly across species. People are a lot more open to it now than they were: about seeing the emotional complexity of animals and giving weight to relationships with them, or just weight to their role and space in the world. My art is about the animal protagonist and trying to look at animals as individuals acting to their own purposes, for their own reasons—and not as symbols or metaphors or objects of beauty.

To see an animal as an individual, I think, has been my goal. If I could accomplish something larger that through empathy and some insight into the animal as an individual, then it would change and heighten people’s attitudes toward animals and eventually that could have an impact on animal welfare. Even just at the level of somebody thinking twice before they cut a tree back where several animals live. Sometimes it’s a small thing. I want the artwork to either arrest or beguile the viewers’ physical senses too. I think that’s important. That’s part of the emotional component of art.

You’ve lived in New Orleans since 2002. How would you say the city has affected your work?

I maintain what you would call a bit of a photographic diary. I spend a lot of time outdoors in New Orleans, in the parks and finding the wild bits among the city. A lot of it’s in the company of other animals, like dogs. I was thinking recently about my relationships to green and how it, living in New Orleans, shifts your palette and what you see and the kinds of patterns I look for.

In another less natural way, I’m affected by things. Just the mechanisms of getting through a dog walk. It’s something you do as part of the devotional care of an animal and for their health and well being. I live in a neighborhood where there is a lot of road construction. I started watching closely and seeing what my dog, how her body interacted with cones and spray paint and started seeing in a whole new way. It’s not just what her senses tell me to look at, but also how she’s using her body in the conversation. The way she does that is to do this millisecond alignment of her body, where she says “There’s that. I recognize it.” And she’s on to the next thing but she knows I see it.

How am affected by New Orleans? I lost my studio to Hurricane Katrina years ago and it affected entirely how I made my art. Steady Star came out directly from trying work in more reproducible, portable ways because I was still in the frame of mind of how to flee a hurricane.

When I first got here, I rented near City Park and would walk under the 350-year-old oaks, just memorizing them and taking a series of photographs at different times of the day. I have a whole body of non-primarily animal-based work that started explicitly out of those trees and the offshoots of looking at oak trees and how oak trees are drawing their shadows on the ground, their reciprocal selves as the light changes.

What you think an art career or being a practicing artist has done for you?

When you’re younger, you have all the anxiety of trying to know who you might be and how you’re going to survive in the world. How you’re going to keep a roof over your head and all these things. There can be a lot of active discouragement against becoming an artist. It’s seen as impractical. When you choose to be an artist, it’s not really a choice—it is who you are. Working as an artist has meant that my predilection towards probing and interrogating things and thinking deeply about things and opening my senses up to what, particularly the natural world, gives back. It’s a life that enables constant learning. It can involve a lot of uncertainty because if you push yourself, you don’t know if you can do things, and you don’t know if you can find the maximal expression of something. It’s a very fulfilling way to live, that ability to think, explore materials. It combines aspects of philosophy, engineering, ethology, being a naturalist.

I think being an artist means never thinking I’m an expert at anything and always trying to make sure that I’m exploring the edge of things. The edge of comfort, the edge of knowledge, the boundaries between who I am as a person and who an animal might be, or even a tree.

I am a part of artist collective, which has been an unusual feature to New Orleans, particularly post-Katrina. It has been an instrumental thing as an artist because you can still work alone and have your imaginative autonomy, but you have want amounts to artist teammates and you’re working together to make opportunities for other artists. That’s been something unusually rewarding in New Orleans in particular.