Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825), Murder of Geta, c. 1782, Gray ink and wash on paper, 9 3/8 x 11 7/8 in., The Muriel Bultman Francis Collection, 86.177

Paper Revolutions: French Drawings from the New Orleans Museum of Art features rough sketches, preparatory studies, and finished drawings by some of the greatest draftsmen of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: Neoclassicists Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix.

This focus exhibition situates these drawings and their makers within the turbulent political context of the Age of Revolution in France, here roughly defined as 1789 to 1870. Amid rapid changes in regime, from monarchy to republic to empire, artists continued to draw obsessively. The French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, established in the seventeenth century during the reign of King Louis XIV, had emphasized the importance of drawing as a pedagogical and preparatory tool. Draftsmanship remained essential to artists throughout the revolutionary period.

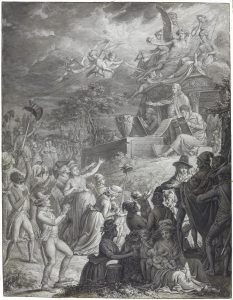

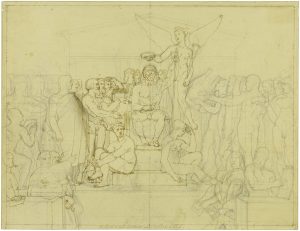

Ingres, for example, produced over two hundred drawings in preparation for his iconic painting, Apotheosis of Homer—including NOMA’s compositional study. The painting—a representation of the ancient Greek author of the Iliad and Odyssey surrounded by philosophers and painters—was commissioned by the restored Bourbon King Charles X. Just three years after Ingres finished the painting, however, Charles X was deposed by the July Revolution of 1830 and replaced by the Orléans King Louis-Philippe I—a descendent of Philippe II, duc d’Orléans, Regent of France from 1715 to 1723 and the namesake of the city of New Orleans.

Like Ingres’s study for Apotheosis of Homer, the drawings on view in Paper Revolutions are intimate in scale. They represent a range of media and different degrees of “finish,” from fragmentary chalk sketches to fully realized compositions rendered with pen and ink. In Ingres’s preparatory drawing, for example, one can see the artist still in the process of formulating his ideas: mistakes, changes, reinforced lines, and scribbled notes are all recorded on the page.

Because drawings offer insight into an artist’s practice, drawings captivated collectors in the Age of Revolutions and beyond. According to the handwritten inscription at the bottom of the Apotheosis study, Ingres gave the work to his friend Frédéric de Reiset, an art historian who went on to become curator of drawings and prints at the Musée du Louvre. Later in the nineteenth century, the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas acquired the study for his personal collection. Degas’s own love of drawing had been inspired by a youthful encounter with the elderly Ingres, who reportedly advised him, “Study line, draw lots of lines, either from memory or from nature.”

Several drawings on view in Paper Revolutions,including Ingres’s study, were given to NOMA in 1986 as part of the Muriel Bultman Francis collection. This gift was a formative contribution to NOMA’s exceptional holdings of French art. However, works on paper are rarely on view because they extremely sensitive to light; many of these drawings in this selection have not been displayed in nearly a decade.

The generous support of Jason P. Waguespack and the Zemurray Foundation has enabled the research and conservation of these works. Now, students of both art and politics can now rediscover the Age of Revolution in France through the drawings produced during this tumultuous period. Paper Revolutions will conclude on July 14, which marks the beginning of the French Revolution with the storming of the Bastille Prison on that date in 1789, two hundred and thirty years ago.

—Kelsey Brosnan, Curatorial Fellow for European Art