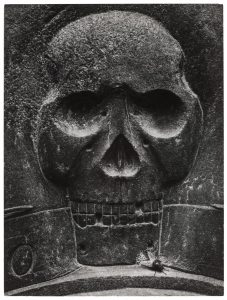

Ansel Adams (American, 1902–1984), Gravestone Detail, Concord, Massachusetts, ca. 1960, Gelatin silver print, 9 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (24.8 x 18.4 cm), Gift of Mrs. P. Roussel Norman, 86.319.1

Ansel Adams is, in one way, a victim of his own success. His best-known images, sensuous and majestic representations of the American West, issued in a variety of formats, have been the subject of multiple catalogs, and remain widely distributed in calendars still today. One photograph even adorned a 3-pound can of Hills Brothers coffee in the 1960s. The problem is not with the commercial success of these images, but rather the way in which their renown has completely eclipsed everything else he did. For example, throughout his career, Adams was apparently always interested in gravestones. Beginning in the 1930s and continuing through the 1960s, Adams photographed old carved headstones in cemeteries from California to New England. He viewed these markers as “profoundly human,” by which he meant to describe the deep personal connection that must have existed between those who installed the stones and those they commemorate. He also, however, valued the craft of the stone carvers, calling it “folk art” and seeing yet another profoundly human dimension in the quality of the work and how that work expressed cultural traditions about life and death. But even within his cemetery photographs, this particular image is an outlier: Adams was careful to explain that his interest in these scenes was not motivated by a macabre obsession with death in and of itself. As a result, his headstone pictures tend to be beautiful but literal descriptions of the stone and its carving and not overtly symbolic, as this one appears to be. A dead fly rests beneath a skull whose expression is more contemplative than frightening, as if this were a twentieth-century meditation on a very common theme: death and the fleeting nature of life.

Such an interpretation might veer too close to metaphor for Adams, but he was sympathetic to its conclusion. For him, the gravestones were not only about what remained but also about what once was. He described these markers as the “closest link I know to the past” and felt they provided “contact with past humanity.” Despite their importance to him, these gravestone photographs remain relatively unknown compared to his landscapes, and yet Adams’s interest in both subjects may originate from a similar concern for humanity’s place in the world. The experience of a vast landscape is not unlike that of considering the deceased through the markers they leave behind. Both make explicit our own limited dimension, in either space or time. To marginalize Adams’s photographs of gravestones, therefore, is to obscure a part of him that informs the rest. Somewhere between the cemetery and the mountain, the humanist and the naturalist collide.

—Russell Lord, Freeman Family Curator of Photographs, Prints, and Drawings

This image and many other photographs from NOMA’s permanent collection are featured in Looking Again: Photography at the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA and Aperture, 2018). PURCHASE NOW

Your gift to NOMA provides critical support for the museum and plays an integral role in all that the museum does, from presenting groundbreaking exhibitions to offering arts-integrated education programs to students across the region.