On Monday, August 21, millions of Americans will turn their sights skyward to view the rare phenomenon of a solar eclipse. New Orleans lies hundreds of miles south of the 3,000-mile swath from Oregon to South Carolina that will be shadowed by a complete blockage of sunlight, but the city will witness the moon covering 75-percent of the sun — a crescent sun over the Crescent City. Artists from the dawn of time have looked to the heavens for artistic inspiration and NOMA invites visitors year-round—rain or shine with no need for protective eyewear—to view the celestial scenes in our permanent collection and special exhibitions. We present here a list of works currently on view that include the sun, moon, and stars.

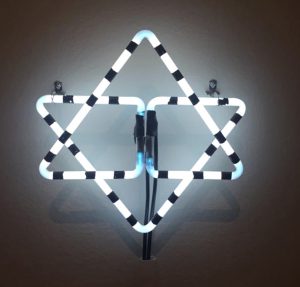

Keith Sonnier, Star of David, undated

As one of the first artists to perfect the use of light in sculpture in the 1960s, Keith Sonnier’s Star of David is a luminescent kickoff to this celestial countdown. Sonnier’s involvement in the Process Art movement emphasized not only the final product of the piece but the action of creating the work, lending intentionality to every creative process. Star of David adds an ethereal touch to an industrial medium, with its illuminating glow and poignant religious symbolism. Sonnier’s work is on view in Pride of Place: The Making of Contemporary Art in New Orleans, an exhibition of more than 70 works from the collection of renowned gallerist Arthur Roger.

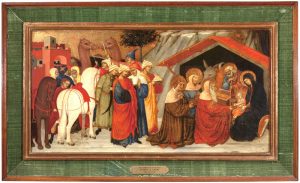

Andrea Vanni, The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1370-80 Tempera and gold leaf on panel, The Samuel H. Kress Collection, 61.61

Andrea Vanni, The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1370-1380

Renowned for his attention to detail and ability to fill a small space with many figures, Andrea Vanni was one of the earliest registered painters in 14th-century Sienna, Italy. This scene, depicting the birth of Christ, recounts the visitation of three kings who followed the North Star from the East to pay homage to the Holy Family. The star, in gold leaf, shines from the panel painting over the manger of the Christ child.

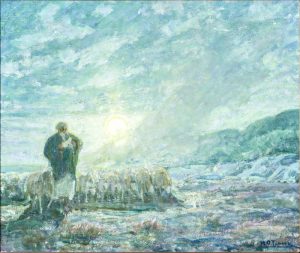

Henry Ossowa Tanner, The Good Shepherd, c. 1914

The moon gleams from this oil painting depicting a shepherd tending his flock. Painted during one of his several trips to the Holy Land, Tanner—the first African American student at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts—was fascinated with religious imagery as a way to deal with racial injustice. Much like the shepherd in his painting, Tanner hoped to guide others towards a spirit of compassion that might, as he notably said, “make the whole world kin.”

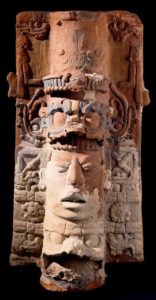

Cylindrical Incensario Depicting a Sun God, circa 600-900 C.E., Mexico, Chiapas

Incense burners like this example have been found by archaeologists in the ancient Maya city-state of Palenque in Mexico’s Chiapas region. The usual decoration is a series of four or five tiered grotesque heads dominated by a realistic human head in the center. The majority of incensarios from Palenque portray jaguar gods or “zip monsters.” This head, however, portrays a sun god indicated by kin, or “sun,” glyphs, resembling an “x,” on the lateral panels.

Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Morning, Port Scene (detail), 1780, Oil on canvas, Museum Purchase and Gift of Edith Rosenwald Stern and Muriel Bultman Francis, by exchange, 96.11

Claude-Joseph Vernet, The Morning, Port Scene, 1780

In this French scene, you are able to stare directly into the sun in the middle of the painting—just like you can the day of the solar eclipse. Struggling to break through the hazy morning and shine on the industrious port, the sun takes center stage at this daybreak scene. Commissioned to portray the various working waterways of France during a productive period for the country, Vernet painted a port scene filled with diligent fishermen and productive workers.

Jim Steg, Moonscape #1, 1963

Full and gleaming, Steg’s moon beams as the focal point of this print. As a notable New Orleans printmaker, Steg experimented with many different printmaking processes—often combining several methods or inventing his own—for a desired visual effect. An innovator and artist at the forefront of many twentieth-century art movements, Steg taught at the Newcomb College at Tulane University and has works in permanent collections at over sixty institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Institution—and of course, NOMA.

Newcomb College Pottery, “Moonlight and Moss” Vase, 1924, Decorated by Anna Frances Simpson, Form thrown by Joseph Fortune Meyer, Glazed earthenware, Gift of Mrs. Isidore Newman II, 2000.506

Newcomb College Pottery, “Moonlight and Moss” Vase, 1924

Newcomb College Pottery was a brand of American Arts and Crafts pottery produced from 1895 to 1940. The company grew out of the pottery program at H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College, the women’s academy now associated with Tulane University. The flora of South Louisiana was a recurrent theme in the designs, as is visible here in a moonlit scene of trees draped in Spanish moss.

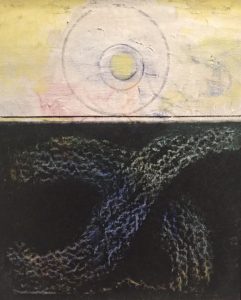

Max Ernst, Gulf Stream, 1927

An artist at the forefront of the surrealist movement, Ernst believed that art-making could call upon subconscious desires and fantasies. Circular and full, the pastel-yellow sun shines from the center of this painting, over a waterscape formed by an experimental method called “frottage”, in which soft materials are rubbed over uneven natural surfaces in a random fashion until the desired effect is achieved. “Art making”, Ernst insisted, “must be, every time: invention, discovery, revelation.”

Wassily Kandinsky, Sketch for Several Circles, 1926, Oil on paper, laid down on canvas, Gift of Mrs. Edgar B. Stern, 64.31

Wassily Kandinsky, Sketch for Several Circles, 1926

Credited with painting one of the first purely abstract pieces, Kandinsky dropped out of law school and began painting after attending a moving Richard Wagner opera. He believed that—like music—painting should posses an enchanting and otherworldly power on the viewer. Kandinsky believed that the circle was nature’s most evocative and essential form, and saw it as “the greatest synthesis of the greatest oppositions…combin[ing] the concentric and the eccentric in a single form, and in equilibrium.” The overlapping circles of this piece are highly resemblant of an eclipse, with imaginary moons and suns passing each other in paint.

Ciwara Association Crest Masks, Bamana Peoples Region, wood, tin, iron, partial and promised gift of Barbara and Wayne Amedee, 2003.160.1-.2

Ciwara Association Crest Masks, Bamana Peoples Region

Ciwara Kunw, antelope crest masks, are among the most recognizable African art forms. They are part of a large collection of objects, actions, songs, drumming, and oral narratives of the Ciwara Association of the Bamana Peoples who celebrate agriculture. In this region, working the soil is a grueling task. Individuals who excel are given the praise name ciwara—“farming beast.” These masks are worn to perform annual rites of renewal and purification in which masqueraders travel across the village to visit spiritually significant locations. Today, Ciwara masquerades frequently function as entertainment. Antelopes are considered to have a tremendous amount of spiritual energy exhibited by their grace and beauty, and they are represented stylistically in these masks worn on top of the head. Other aspects of these masks symbolize key components of agriculture. The zigzag pattern, which typically forms the neck, marks the sun’s path between the period of solstices and/or the bounding stride of the antelope.