Visitors to the exhibition A Life of Seduction: Venice in the 1700s immediately notice the frequency of masking in many of the paintings. Indeed, Venetian Carnival lasted nearly half the year in the 18th century, but the phenomenon of facial disguise took on greater significance than holiday revelry. On Friday, March 24, James H. Johnson of Boston University will deliver a lecture entitled “Masks and Identity in Casanova’s Venice” at 6 p.m. in the Stern Auditorium. Vanessa Schmid, NOMA’s Senior Research Curator for European Art, also examines the role of masking in Venice in frequent noontime talks and in this feature story, an online exclusive from Arts Quarterly.

In NOMA’s A Life of Seduction: Venice in the 1700s, two 18th-century masks are on view in the final gallery. Masks are exclusively associated with Venice, and various paintings in the exhibition depict masked citizens of the Republic. In the galleries, lively discussions about masks – their role and the traditions and origins of masking — have prompted this article.

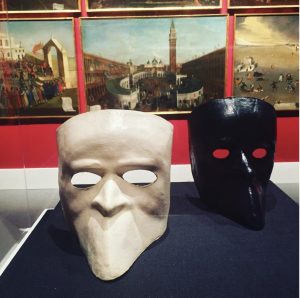

Venetian Manufacture, Two Bauta Masks, Late 18th Century, Cloth and painted gesso, Venice, Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

The emblem of Venetian Carnevale was the mask. Deriving from the theater, the wearing of masks is intuitively associated with roleplay, while it also adds a sense of intrigue and ambiguity to social interaction. In Venice of the 17th and 18th centuries, the combination of the mask with the black cape and tricorn hat symbolized the Carnival season, as in Pietro Longhi’s exquisite painting The Perfume Seller. The city’s revelers enjoyed an extended Carnival season that began in early October.

While masking was associated with Carnival, Venetians did not wear masks solely for celebration. In fact, for almost half of the year masks were worn to social gatherings, to attend the theater, and for evening outings. The practice coincided with the six-month theater season and was considered a remarkable and defining feature of public life.

The liberating effect of the mask was routinely remarked upon in the period. The practice provided a release from strict moral codes implemented by the city’s conservative Great Council. The city’s censors decreed a baffling array of laws regulating conduct, and sumptuary laws controlling the excessive display of wealth. The densely populated islands of Venice were home to a remarkably diverse population of 130,000 inhabitants, coming from Mediterranean colonies and the far reaches of the Republic’s trade networks. This density and diversity appears to have catalyzed already from an early period close oversight of public behavior.

At first glance, the wearing of masks is associated with disguise and mimicry. The sociology of masking in Venice however proves more layered and compelling. In a culture structured in a rigid social hierarchy, the mask offered not just relief from strict codes of behavior, but a deeper liberation born of its equalizing effect on social differences. Creating an appearance of equality, the mask eased the interaction of social classes, permitted women to go out unescorted, and allowed beggars to conceal their shame. And, of course, as profusely and notoriously demonstrated by Casanova’s exploits, the mask’s secrecy enabled a certain sexual freedom.

The anonymity of the mask was relative, of course. A member of the noble classes could easily be identified by his servant and masks varied in quality and type. The bautta mask, for example, was reserved for the nobility and uppermost middle class and was required at official ceremonies. The black moretta was worn exclusively by patrician women. The shape of an oval disc, the mask was kept in place by a button clenched between the lips or teeth.

The philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin analyzed the dynamics of carnival and popular culture in Medieval and Renaissance Europe. His concludes that masking as a practice is fundamentally about unmasking, that is: disclosing the unvarnished truth. The distancing effect of the mask allows for and even encourages a degree of anonymity, releasing the wearer to an unknown world. At heart, Carnival and masking in the Early Modern Period was a part of the evolution of selfhood and the construction of social identity.

The social lubricant masking provided came at a vital time in the city’s history when social tensions ran high. By 1700, Venice’s political and economic status had been waning for over a century and the remarkable pageantry and splendor in civic life served to camouflage this situation. While Venice was able to create and project a self-image as a cultural capital, the failing economy resulted in significant demographic shifts and visible effects in the city. Many noble families retained their social status despite depleted incomes and poverty became a pressing social concern, having tripled by middle of the 18th century. City officials had every reason to fear unrest might result in violence, and it has been suggested that the remarkable frequency of festivals and community-based events in the city’s squares —occurring at least two times each month — was part of a strategy on the part of the Venetian authorities to regulate and placate the population and diffuse discontent. For Venice in the 18th century, the theme of disguise is many-layered.