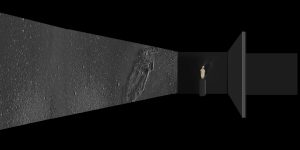

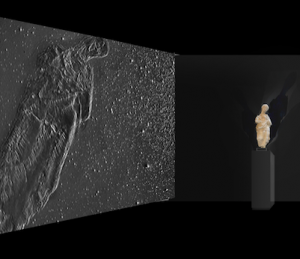

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), Concept rendering for Where’s Mary, 2020, Digital projection and found marble sculpture, Dimensions variable, Collection of the artist, © Dawn DeDeaux

Dawn DeDeaux: The Space Between Worlds is the first comprehensive museum exhibition for pioneering multimedia artist Dawn DeDeaux. Since the 1970s, DeDeaux has spanned video, performance, photography and installation to create art that exists at the edge of the Anthropocene, anticipating a future imperiled by runaway population growth, breakneck industrial development, disease, and the looming threat of climate change. In the face of the existential threats we all face, her art presents us with a limited-time-only opportunity to come together and coexist.

Dawn DeDeaux: The Space Between Worlds, previously scheduled for fall 2020, will now premiere at NOMA in fall 2021. In the days just before the lifting of the lockdown, DeDeaux spoke with exhibition curator Katie A. Pfohl about the silver linings of this pandemic “pause,” and finding hope in what feels like the end of the world.

Your upcoming NOMA retrospective The Space Between Worlds includes art from the 1970s through today. Looking back on the last forty years of work, what do you think have been your most urgent questions? The stuff that keeps you working, and keeps you up at night?

Well, one thing that keeps me up at night is trying to sum up the mysterious math of life, right? It’s such a miraculous experience—the speck of me, here, against the backdrop of vastness! What are the odds that the numbers came together in such inexplicable ways, giving us the exact chemical equation for life? Or did God throw the life symphony together in an epic six days, and then have a cocktail?

Like many, my trajectory is shaped by my childhood. Early tragic events framed how I see the world and led me to a vocation in art, initially for its healing properties. Importantly, there was an early recognition that I was not alone in a tragedy, and I saw myself in the face of others on the stage of the streets and upon the pages of art history. As a recipient of the greatest circumstantial gift of empathy, you understand that you are a part of a collective human family. Empathy illuminates the frailty and impermanence of people and place, and shows us how interconnected we are with all other planetary life systems. This totality and impermanence steers all of my work.

Since the 1970s, your art has worked to heal the divisions that exist in society—to help us see that we are all part of the same shared struggle. As we live through this moment of “social distancing,” this question seems all the more urgent: what role do you believe art can play in creating a sense of community and common purpose?

In my early career projects, my art aimed to cross race and class divides. As a young girl growing up in New Orleans, I was witness to racial discrimination during the civil rights movement and the fallout of white flight. Over the course of a very few years, I became the sole white minority in the several blocks surrounding my home. My comparative observations of my downtown neighborhood, juxtaposed with my dominantly white uptown school and social life, illuminated the stark inequalities that defined life in New Orleans at that time.

In response, I began harnessing new media as my medium, and democratic communication as my fuel for engagement. Mass media exponentially increased my pool of possible participants. It helped me nurture exchanges between different communities across the city that weren’t really talking to each other.

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), CB Radio Booths, 1975-1976, Installation of nine CB Radio Booths at various locations in South Louisiana, Collection of the artist, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

One of my most important early projects is CB Radio Booths. It was conceived to temporarily suspend race and class barriers by creating opportunities for anonymous exchange. The project was a free communication network that linked random strangers in conversations on a channel designated just for the project by the FCC. CB radios were installed into gutted outdoor telephone stands, then placed in multiple sites throughout south Louisiana over several months. The project was a success and widely used by many different communities across the city. In the pre-internet era of the mid-1970s, CB Radio Booths is one of the earliest examples of free “social media.”

During the 1960s and 1970s, art institutions offered little access to over half of the population. My projects had to simultaneously build up art access and art audience. Therefore, I decided to bring my art into the streets. My roving project Drive Up Movie screened art films onto random exterior walls with a generator and a drive-in movie projector. A few years later, Art in America: A Traveling Show launched a fleet of Winnebagos, each transformed into an art installation, to drive around town for mobile exhibitions in a number of underserved neighborhoods.

In the late 1980s, I created a project called America House that aimed to give larger representation and audience to the most marginalized members of our society, many of whom were incarcerated. Here again, I used video media to give a voice and platform to the silenced. Inside a sequence of rooms, videos conveyed the stories of participants who shared with viewers poignant accounts of their life. Marking the entrance to each room was a life-size photograph of a domestic door with decorative security iron work, gesturing that we are all in this prison together. These doors, a-topped with motion detector lights, also identified the fever of fear that was assaulting New Orleans at a most violent time in its history.

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), America House (partial view), 1991–1995, 10 life-size translucent photographs applied to doors with acrylic cover; motion detector lights, 10 video installations (one per room), studs, drywall, and ambient sound, Dimensions variable, Collection of the artist, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

You expanded this focus on social justice to include the environment. Your work shows us that we can’t talk about climate change and sea-level rise without thinking about social inequality. We can’t address disease without talking about pollution. How did you arrive at this realization, so early on?

I lost a sister to cancer and my remaining four siblings are all cancer survivors. It was so unusual because there is no pre-existing cancer on either side of the gene pool. It points to possible environmental toxin exposure. At some point, I realized that the threat of pollution on public health was widespread throughout society, and particularly for poorer communities who are at the greatest risk. Their neighborhoods are often used as toxic dump sites and are more commonly adjacent to hazardous chemical-emitting industrial complexes.

This personal and public concern moved me into the zone of environmental justice and it has dominated my work starting in the mid-1990s. During this time, I produced a landscape series for the Aldrich Museum’s show Landscape Reclaimed that really solidified this commitment. The series addressed our increasingly imbalanced world, picturing landscapes degraded by industry and failed planning, accompanied by videos of disrupted animal environments.

In works of the past decade, I am responding to a new hierarchical set of issues that threaten our very existence. I have moved from micro investigations of city and country to a macro focus on the delicate interdependency of global eco-systems. In these more recent projects, I am working with new strategies of engagement, but ones that relate in spirit to my past work. For example, the NOMA retrospective will include Souvenirs of Earth, which takes as its premise Steven Hawking’s prediction that humanity has 100 years—not to save the planet but to leave. And that was over 15 years ago! Souvenirs of Earth will have an interactive component that invites people to identify what small object they might take with them, if forced to flee the planet. It combines everything from seeds and raw earth to postcards of famous paintings, frayed books, models of famous monuments and historical sites, and ashes and knots of hair. It reduces the larger debates about our climate and the future of human life on our planet to an intimate, personal scale, and invites people to be part of the conversation.

These souvenir offerings will form a wall in the exhibition in association with a large work titled Dirt Bowl Table, that brings together earth samples from around the world, which I am working on for NOMA in collaboration with The Transart Foundation for Art and Anthropology in Houston.

You lost much of your art studio and archive during Hurricane Katrina, and a big part of this exhibition is reconstituting many of your past projects, as well as reimagining them for present day. Out of all of your past projects, what do you think you are most looking forward to presenting at NOMA?

Oh, I can’t pick a favorite among my children! But a few of the projects were near dead, and would never have been seen again by the public were it not for the retrospective, so I will acknowledge one of my most “at risk” projects, Face of God, in Search of.

Dawn DeDeaux (American., b. 1952), The Face of God, In Search of, 1996, Six synchronized video projections, metal bed, 50 x 46 x 12 feet, Collection of the artist, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

Face of God is a multichannel video sculpture that I presented at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta that really marked my shift in focus toward environmental justice. In its day, it was a breakthrough technical work, using six synchronized projectors to create one of the first fully immersive media environments. It centers on my reimagining of Tennessee Williams’ play Suddenly Last Summer. The protagonist is a man of privilege named Sebastian: a self-proclaimed poet who affords himself vast travels around the world in a quest to find/see the face of God, which he hopes will inspire the greatest of his poems. At last, Sebastian sees God while witnessing bird and iguana predators feed upon hundreds of hatching sea turtles. I have always been uncomfortable with Sebastian’s God, found in the drama of consumption. My God is not there.

Instead, Face of God aims to represent our collective struggle to survive in the face of both natural and human-induced threat. It highlights nature’s paradox—its ability to be both majestic and indiscriminately cruel. Within the installation, the environment vacillates in extremes: at times open, seduced by breeze and moonlight, and then closed in threatened outbreaks of stormy violence. By showing us nature’s cruelty and violence, we recognize ourselves center on the stage. The irony is that Sebastian failed to grasp himself as the main predator on the beach: it is man, not bird, who proved to be the greatest threat to turtle, driving the species to the very brink of extinction.

The master tapes were badly damaged by Hurricane Katrina and a few unsuccessful video transfer efforts. I am now reconstructing Face of God with two surviving Hi-8 video source tapes and access once again to the Audubon Society’s film-archive library. I used footage from this archive over twenty-five years ago when I first created the work. I am grateful to have access to this original footage so that the reconstructed work will be a near perfect match to the original 1996 version. We’ll make it work!

You are also creating some new, hugely ambitious installations for the exhibition—can you share a bit about what you are working on, and some of the ideas you are processing?

Among the three major new works underway for the retrospective, I am creating a new immersive video installation titled Where’s Mary? that will stretch across a seventy-foot wall, filling a large room at the rear of NOMA’s main exhibition space that is rarely used for art. The installation is an extension of my long-running Souvenirs of Earth series, described earlier, and ponders the trajectories of remnant things lost and floating through space, detached from lives and function.

Dawn DeDeaux, Detail from concept rendering for Where’s Mary, 2020, Digital projection and found marble sculpture, Dimensions variable, Collection of the artist, © Dawn DeDeaux

The star of Where’s Mary? is a marble statue of the Virgin, or a resembling goddess, that I discovered in a shop of curiosities. It is eroded by time and water, appearing to have been tossed and turned by the tides for centuries. The figure is barely recognizable, but has a mysterious, pregnant power. As the subject of a multichannel video projection, the sculpture will float through an uncharted terrestrial plane, lost in space. Already identified with our past, she becomes our future ruin. Among the few surviving remnants of civilization, Mother Mary pulls us, hopeful, into her orbit in an attempt to trace evidence of our humanity.

As we are confronting the upheaval of this pandemic, your work has never felt more important or more relevant. It is clear that you saw this pandemic—or something like it—coming. You’ve been anticipating the apocalypse for years! How do you think your work informs your response to our present moment?

While I have been depicting apocalyptic scenarios for the past decade, I, too, am startled because I did not anticipate that I might still be alive to experience this first episode—The Pause—this moment in which global human activity has come to a stop. Many note their woozy time-warp sensations, and one wonder’s if the earth itself has stalled its spin?

I am sorry for all the human suffering, deaths, and economic dreams lost. But as a student of apocalypse, I am grateful to be alive to observe and experience our passage into a new age. Clearly, we are not facing the end of the world this time around, but the world as we knew it has forever changed. A plethora of news updates remind us of our reduced water and air quality, cracks in the food chain, and the radical breach in global public health we now face. It is a wake-up call. The mainstream is finally absorbing the fact that unless we change the rules to live by, we may not live at all. This is no longer drill. The future is here.

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), Parlor Games, Mantle Souvenirs and I’ve Seen the Future It was Yesterday, 2017, Installation view of Thumbs Up for the Mothership (MASS

MoCA, May 27, 2017–July 8, 2019, with Lonnie Holley), Courtesy the Jack Bakker

Collection, Amsterdam NL, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

In my MotherShip projects, I peer towards a future when humanity is forced to flee earth due to environmental degradation, plagues, and Darwinian wars to claim the last life-sustaining resources. I parallel ancient mythologies that foretell the end of time with present-day environmental projection statistics that calculate a future with a similar ending: an apocalyptic dissolution of human civilization. What if myth and science are right? What if Earth becomes too toxic and to survive as a species we really have to leave? Where are the ready-made Noah’s Arks? Save for those few wealthy folks buying up land and building bunkers in New Zealand, the rest of us will have to jump ship. We will become the planet of refugees.

Harkening back to my early work that focused on equal rights, I fret over the quantity of airships and their seating capacities: with mass exodus becoming a more plausible construct—and with a projected population of 9.5 billion, I once again place, front and center, this looming ethical question: Who gets a seat on the bus?

So much of the imagery from the MotherShip project—people in hazmat suits, cordoned off in containment zones—looks like it could have been taken straight from the front pages of the newspaper in almost any city in the country right now. Who are the people you place at the center of these apocalyptic scenarios?

The people? Me, my friends and neighbors, strangers on the street, the NOMA staff and members, a bartender, and all ye gentle readers—we are at the center of the apocalypse. Beginning with the staging of MotherShip II: Dreaming of a Future Past in 2014, I found myself leaving the myths and math behind, and started to zoom in on the human drama. What is happening to us in this phase of disorientation? What’s our phsychological state of mind? For me, even a mere two months in quarantine has left me a touch stir crazy!

The comic in me asked, “What will we wear?” But really, this is my way of asking what will become of the cultural history we leave behind, and what new art movements will be ushered in as we invent new iconographies, new images of ourselves in a future-tense. For years, I have been testing the appliqué of assorted decorative patterns on survival suits. Flora and fauna will soothe our nerves and quench our nostalgia for planet Earth. Some feared I had succumbed to a Rococo phase, but I assure you these experiments have been data-driven! Just turn your attention to the social media postings during quarantine: you will note that pictures of gardens and flowers score the most likes. Flowers, not religion, is tomorrow’s opium for the people.

But the reality is we need social-distancing spacesuits now. In the past month, I have been heartened by the thousands of people worldwide who are incorporating decor into their face masks to disguise the real horror of having to separate themselves from the toxic nature of pandemic and the beloved. I have been imagining for a long stretch of my career how the membranes of masks and suits correlate to a loss of intimacy.

You’ve focused in on our increasingly urgent need for protection—from disease, from the elements, from each other—since the 1980s. You saw that, in addition to survival, what was at stake was a loss of connection, a loss of community, and even a loss of compassion. How did your early work about the AIDS epidemic shape your thinking about these apocalyptic future scenarios?

I first began designing protective suits for humans during the AIDS epidemic and the need for armor only intensified when imagining the future. NOMA will survey a selection of these works, including a life-size video installation titled Almost Touching You. Here, a Botticelli-like female nude—with a striking similarity to Birth of Venus—aims to dance with a man fully wrapped in plastic, as if in a full-body condom. The couple struggles to touch as a song by Chet Baker, Almost Blue, plays in the background. They aim to hold onto one another in vain as sounds of plastic crinkles in offbeat against Baker’s melody and lyric, still so apt for today: “flirting with this disaster…almost touching will almost due….now your eyes are red from crying, it’s almost you…”

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), Grasping Nature, 2014, Photograph printed on archival paper, 60 x 42 inches, Collection of the artist, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

Later, I started making portraits of people covered with masks, and clad in impermeable suits to shield themselves from the hazards of a violated, vengeful natural world. Whether suited for earthly threats or flights beyond, all these figurative works are generally called Space Clowns—a misleadingly playful title for this dead serious subject depicting humankind’s growing alienation from the natural world. Some of my space clowns appropriate the classic Apollo NASA-style suit, and others came out of photographs I took of emergency first responders wearing their protective gear during my productive residency at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva, Florida. Among my favorite images is a man in white hazmat suit cradling a branch of green leaves, presumably radioactive and too deadly to touch. Another portrait is a responder having to breathe through a ventilator standing before a crisp blue sky and puffs of clouds. His gaze conveys his awareness of the ominous approaching storm of the future.

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), Guardian at the Levee Gate, 2013, Digital imaging on aluminum panel, 38 x 28 inches, Courtesy Arthur Roger Gallery, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

Guardian at the Levee Gate is the very first of my Space Clowns, and was inspired by Louisiana’s own Cancer Alley, a petrochemical refining zone that runs down the edge of the Mississippi River from Baton Rouge to New Orleans. This stretch of land near water is among America’s most infamous examples of environmental injustice, together with a community impacted by toxic air near refineries in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), The Vanquished: G Force #1, 2016, Digital drawing on archival paper mounted to aluminum, 85 x 38 ½ inches, Courtesy the Jack Bakker Collection, Amsterdam NL, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

The conclusion of the Space Clowns series is a grouping called The Vanquished. Within the works, both humans and their protective-membrane barriers indiscriminately dematerialize into a matter both synonymous and indistinguishable from the artwork plane—a deep-space darkness where the debris of dead planets, spaceships, satellites, astronauts and their ventilators all meld into the minutiae meteor-bytes of matter—the domain of my Mary. Let’s now roll the credits and bring up the music: The End.

You grew up on Esplanade Avenue, just down the street from NOMA, coming to the museum all of the time. Despite thinking so much in the future tense, your work constantly calls forth art history. I know all about your not-so-secret love of landscape painting! Why, amidst all of this projecting into the future, do you think you so often look back, too?

It’s true, my love of landscape paintings! It has only increased with my growing melancholy over environmental degradations. I collect, just for myself, very small pre-industrial landscape paintings. I like to surround myself with art that celebrates the virginal bounty of nature. This keeps me balanced and reminds me of why I fight the fight.

I actually studied painting for eight years before I recognized that my work required a different path—a different way of representing the time in which we live. I felt I had to push my art into the streets and onto the screen, but this never diminished my base love for painting, or the need to ensure that all my artistic output possessed aesthetic empowerment, too.

Growing up on Esplanade, I stayed with my grandmother who lived large and always a few steps ahead of her means. She maintained a large old house on her wits and rented out a few rooms here and there to assist with the overhead. One day, a painter named Laura Adams arrived in a taxi with great theatricality—a raven bohemian beauty with a chaotic toss of canvases in the back seat, and a cab trunk that wouldn’t close. What transpired between us awaits a novel, but suffice it to say that she became my mentor and teacher in both art history and painting. I went to school by morning, but in truth I was comprehensively home-schooled by Laura, who stuck around for three years.

She introduced me to theater, beat fashion, literature and somehow convinced my grandmother to allow me to join her on two sequential summer trips to New York where I was introduced to museums, galleries, and a different type of cultural urbanity. In turn, I introduced her to the mysteries of Esplanade, Mardi Gras, my favorite hiding places in City Park—the Christian Brothers School stone grotto then hidden in a dense tropical jungle of palms—and to my Kress Collection at the New Orleans Museum of Art. My favorites included Seascape with the Friars, Agostini’s Portrait of a Man, and that wonderful hat in Romanino’s Portrait of a Man in Armor. I was intrigued by Fungai’s St. Lucy Lead to her Martyrdom and I can still skydive into Sebastiano’s Imaginary Scene with Ruins and Figures. Over the years, I have also come to so appreciate NOMA’s Portrait of a Young Flute Player by Bacchiacca—it is a very early example of a painting that gives equal treatment to both the foreground portrait and the landscape background, a combination that later drew me to Thomas Gainsborough.

Paintings I saw at formative moments constantly find their way into my work. Gainsborough’s paintings—particularly Blue Boy—have inspired my own Space Clown series compositions. I love how Gainsborough celebrated the richness of nature above the interior walls of estates. But today, with growing ecological decay, I portray my own figures with Anthropocene-appendages of masks, suits and ventilators—to coexist with nature.

I still remember seeing Picasso’s Studies for Guernica, along with the large painting, at MOMA in New York with Laura in 1966. It was jaw-dropping to see, and I am sure it helped ignite the art activism I would later embrace. I remembered Picasso’s pale horse study in the first iteration of my MotherShip series, where I explored the role the pale horse played throughout history as a mythic indicator of the end of time. Another memorable, influential exhibition I saw during that time was MOMA’s 1967 exhibition Once Invisible, that presented images that were unseen prior to photography, like the surface of the moon. I already had a serious interest in outer space and this imagery and unique installation, together with Yves Klein’s experiments and Robert Rauschenberg’s terrestrial works, enlarged my vision in both content and form.

In the end, history is the great teacher. I believe there is a duty to study the past if one audaciously attempts to envision the future. Art allows for time travel: you learn when viewing art of prior centuries that the sets and costumes change, but human nature stands still. You find your own face within. The stories of humanity are fully accessible in art history, it is our universal language. We may have new machines and different staging platforms for survival, but to make it all work we have to reckon with the complexity of what it means to be human. That, no matter what happens, will follow us deep into the future.

Right now, I am finding joy and great solace in time-traveling throughout art history, dusting off old essays and revisiting—at least virtually—favorite works of art. What I find there—loud and clear—is that we are not alone in this crisis. Art history shares humanity’s continuum: this too will pass. And my party’s not over yet—as I push into my seventh decade, I look forward to a stretch of time as a Sunday painter, but I will spare the public the results.

Many of your projects also draw upon the work of our great writers and philosophers, finding within stories of destruction and redemption lessons that might lead us on a better path. Why do you so often cite literature?

Writers have inspired me and often appear as companions in my art. From the classics, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and Dante’s Purgatorio influenced the imagery in Soul Shadows, my long multimedia corridor that featured silhouettes of incarcerated youth with whom I worked over a stretch of years. Both my Prison Project book and my glass-ladder sculptures are inspired by my favorite Virgil passage from Aeneid: “…easy is the descent to Avernus: night and day the door of gloomy Dis stands open; but to recall thy steps and pass out to the upper air, this is the task, this the toil!”

I also turn to Boethius’s fifth century book Consolation of Philosophy in my Goddess Fortuna project, which also considered elements of John Kennedy Toole’s book Confederacy of Dunces. Among the most important words ever scribed about how we endure life’s fickle-finger surprises—such as this pandemic—are offered up by Goddess Fortuna in conversation with Boethius: “One’s virtue is all one truly has, because it is not imperiled by the vicissitudes of fortune.”

Milton’s Paradise Lost is literally the crux of my large-scale sculpture installation Free Fall, in which selections from the epic poem appear on forty-eight concrete columns, installed at angles as though in a state of fall. This project first appeared at the Open Spaces biennial in Kansas City in 2018, and will be reinstalled in New Orleans this fall, down the four block neutral ground facing the Superdome as part of The Helis Foundation Poydras Street Sculpture Project. While I was working on Free Fall, I had a personal eureka moment during my immersive study of Paradise Lost and the biblical Garden of Eden. I realized that the story of paradise lost is actually a tale about our future, not our past: this is the paradise, NOW, if we can save it. In moments such as these, we have the chance to rewrite the story, and loose the forecast of expulsion. The Pause. Will this mark our new beginning?

Dawn DeDeaux (American, b. 1952), Speaking in Tongues (detail), 2012, Translucent polished acrylic with fused text, 142 x 15 x 3 inches, Collection of Marc Olivie, Photo by Dawn DeDeaux, © Dawn DeDeaux

What are you working on now? Do you think aspects of your retrospective will change, as a result of all that is unfolding?

Oddly enough, the simple answer would be no.

The themes of my work over the course of the past decade have explored the likely scenario of pandemic and ecological degradations that would reshape human life and culture. This thematic buildup started with Hurricane Katrina and was reinforced by the BP oil spill, as witness to the mortal passages of my parents, and my front-row seat watching Louisiana’s coastline slip into the sea. These episodic chapters enlarged my vista of “future,” and the retrospective selections reflect this view. The work remains inherently now. You will find no Covid-current-event here, for we are beyond. My own vocational job description is not about now, but next.